Local Spotlight

Naperville, Illinois

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

Community Profile

- Community: Naperville, 1831

- County: DuPage and Will

- State: IL

- Type: Suburb

- Metro: Chicago

By the mid-18th century, the Potawatomi lived in much of what would become Chicagoland. In 1831, a settler party from Ohio founded Naper's Settlement along the DuPage River. By the 1840s, German, Scottish, and English immigrants started arriving. Naperville was almost exclusively White during the mid-19th to early 20th centuries with few exceptions. The community’s mid-20th century transformation was spurred by significant physical and population growth. The suburbanization of the 1980s and 1990s accompanied increasing diversity that continues today. Naperville is Illinois’ fourth largest city with a population that is 69% White, 20% Asian, 7% Hispanic, and 4% Black.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 75.6%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $416,700

- Median Gross Rent: $1,516

- Median Income: $125,926

- Poverty Level: 4.3%

- High School (ages 25+): 96.9%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 68.2%

Data Sources

Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice

Census Quick Facts, US Census Bureau

Forbes Best Places to Live

Planned Exclusivity Defines Twentieth Century Growth

Located in metropolitan Chicago and considered a quiet community of farms and light industry, Naperville, IL in 1890 bore little resemblance to the booming technoburb of the twenty-first century. For over 80 years, Naperville was a sundown town.Sundown Towns: All-white communities or counties that purposefully maintained their status through harassment, discriminatory laws and ordinances, and violence or threat of violence. The name comes from posted and verbal warnings that Black people and other people of color would receive upon entry. Sometimes this status was codified in law and signaled with signs, sirens, or other warnings. Often, laborers such as household, farm or factory help could work in a community during daylight hours and had to leave town by sundown. Frequently, it was maintained by practice and custom of local people and law enforcement. Sundown towns appeared in many areas of the nation between 1890 and the 1970s with some still maintaining their all-White status. Its growth was shaped by exclusionary practices including racially restrictive covenantsRestrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group. designed to ensure an all-White community. Before the 1960s, few community members called these practices into question. Later, employees filed legal complaints against their employers and activists pushed for fair housingFair Housing : The assertion that people ought to determine the roof that they want over their heads without unlawful discrimination based on race, age, sexual orientation, religion, ability, or any other protected class. Commonly referred to as open housing in the mid-twentieth century, the fair housing movement and racial integration in communities were core demands of the Civil Rights movement. to expand access to people of color. In 1969, Naperville was essentially an all-White community. Today, it is a community significantly changed, with 32% people of color, primarily of Asian descent.

We form a called Naperville Chinese Association. And so the association took over the celebration of Chinese New Year and evolved and became bigger and bigger every year.

Community Leader

ViewHide Transcript

When we moved to Naperville, there were only maybe six or seven families. And yeah, in those days and we got together for dinner and then we got together for New Year's parties. And that lasted for several years until Naperville, until the Chinese-American population grew bigger and bigger. And I always remembered that we were the last family to host a New Year dinner at our house. And at that time, I think there were about 15 families. I would say that would have been around 1976 or so or 1975. And then it got so big, people say, “Well, we can't hold that at our house anymore.” Nobody wanted to offer their houses anymore. And then we start looking outside. I can't remember where we held. I don't think it was the high school, because it wasn't that large, but we held it at a public place. And so then surpassing by 1979 or 1978 that we form a called Naperville Chinese Association. And so the association took over the celebration of Chinese New Year and evolved and became bigger and bigger every year.

Centennial Beach was segregated from its opening in 1932 until the 1950s. This was not a formal policy, but a custom that successfully kept Black swimmers out of the Beach. The first attempt to desegregate the Beach occurred in 1946.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

Throughout the nineteenth century, Naperville and most of DuPage County excluded Black people and other people of color from settling and working locally. In a 1907 Chicago Tribune article, a resident of neighboring Glen Ellyn pointed to Naperville as a model for exclusion, stating, “In Naperville they have no colored colony. They will not sell land or anything else to negroes or give them work, and they stay away. Negroes will lower the price of real estate. Do we want them here?”

Naperville embraced its position as a Chicago suburb in the 1950s. Moser Highlands was one of the first subdivisions to turn farmland into tract living.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

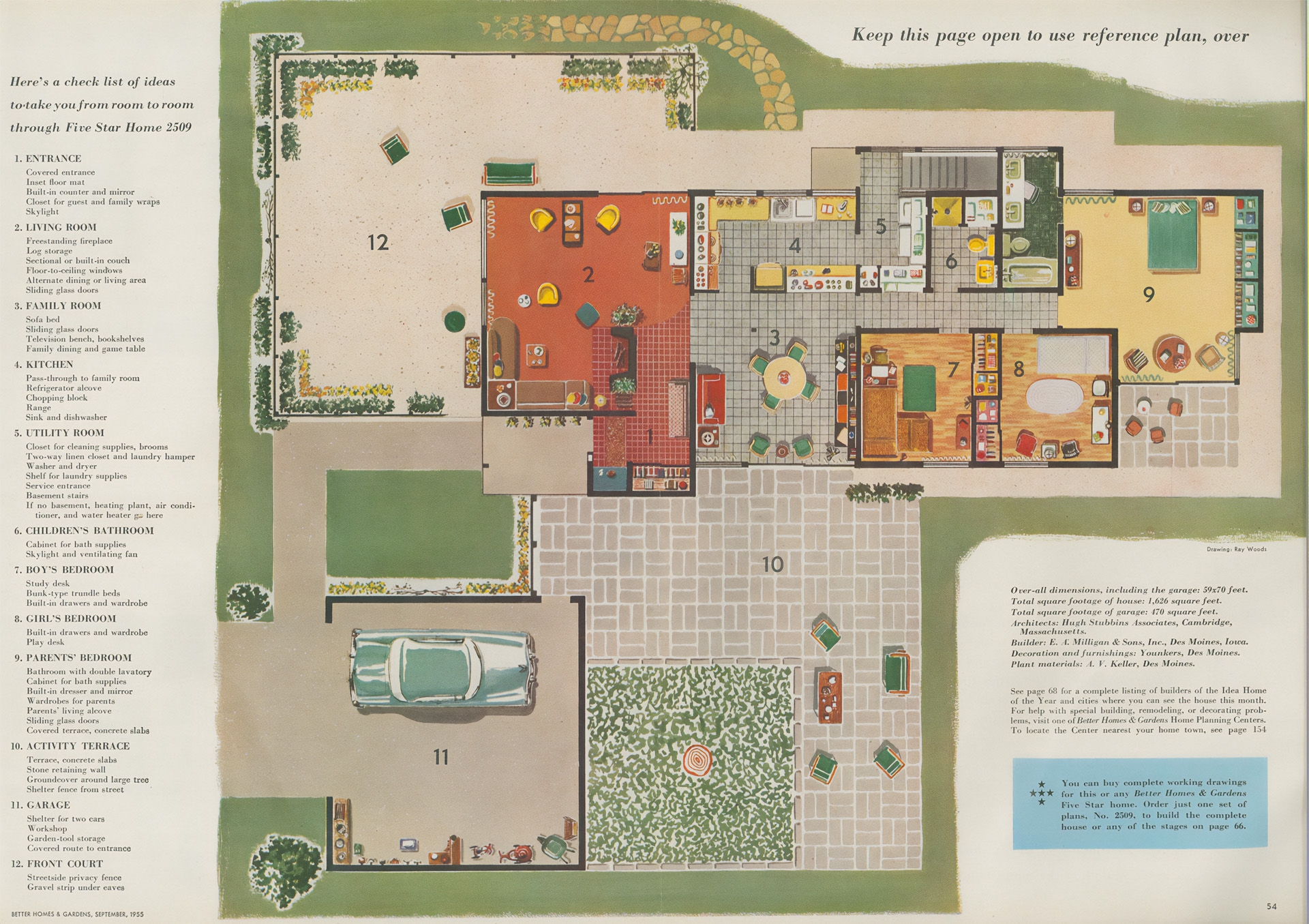

During the mid-twentieth century Naperville grew into a Chicago suburb. Between 1950 and 1980, Naperville completed 240 land annexations,Land Annexations: The incorporation of new land into a city or county. primarily of farmland, sparking intense debates about what Naperville would grow to be. As early as the 1920s, Naperville landowners and developers put racially restrictive covenants in property deeds that prevented individual homes from being conveyed or leased to any person “not a Caucasian.” Although these types of covenants were ruled legally unenforceable by the US Supreme Court in 1948, they continued to appear on Naperville property deeds into the 1960s. In 1954, the City Council approved a suburbanizationSuburbanization: The process of movement from urban areas to developing or planned communities outside the city limits. ordinance that started a housing boom. This ordinance set minimum standards for home and neighborhood construction to ensure that Naperville building would always be “of the highest quality.” Excellent schools, along with the construction of the East-West tollway (made possible through the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956), made Naperville a desirable place for suburban living.

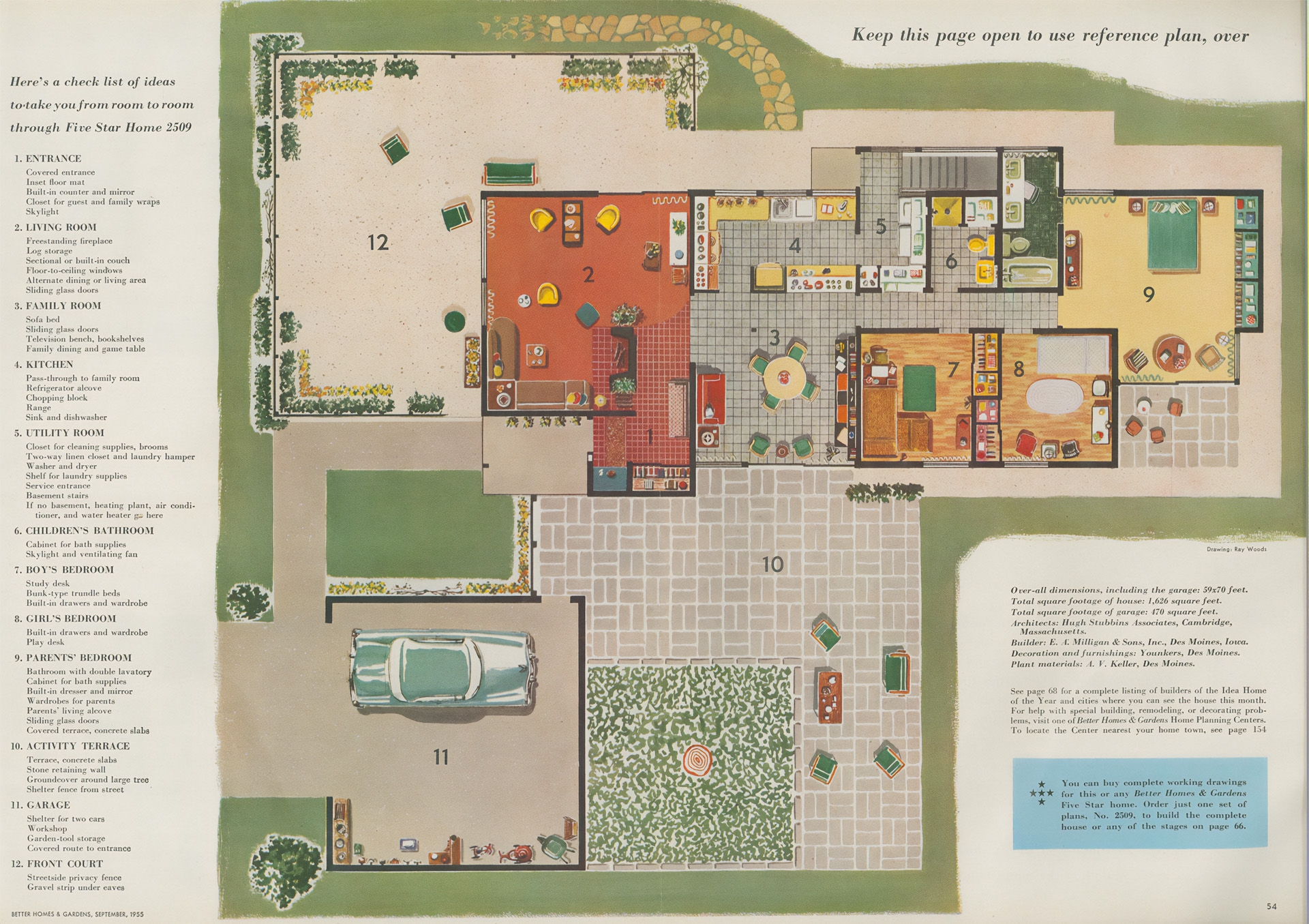

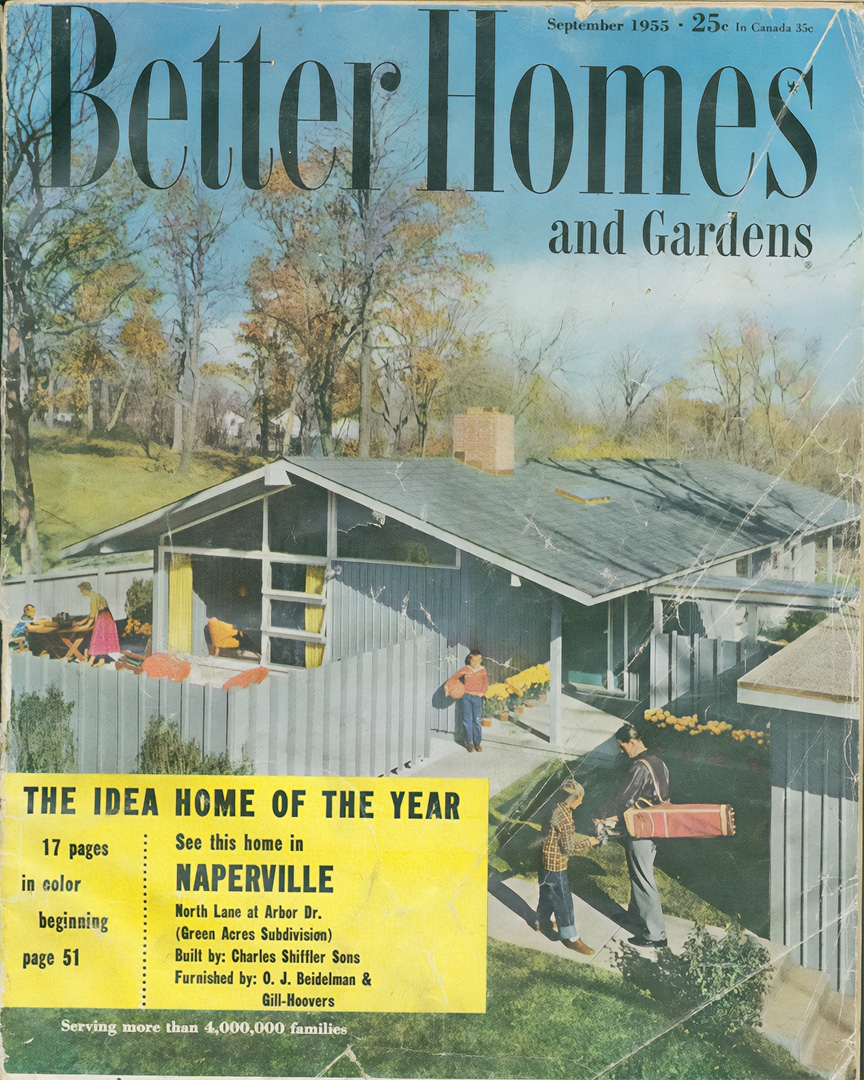

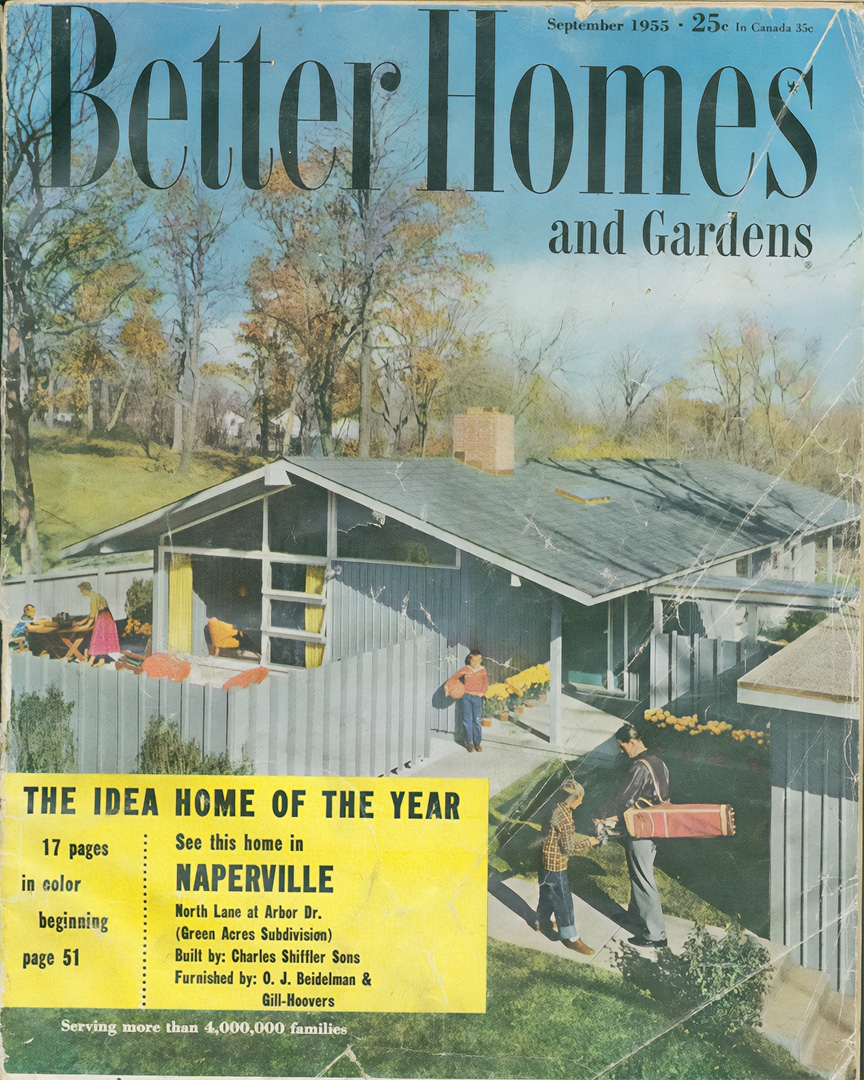

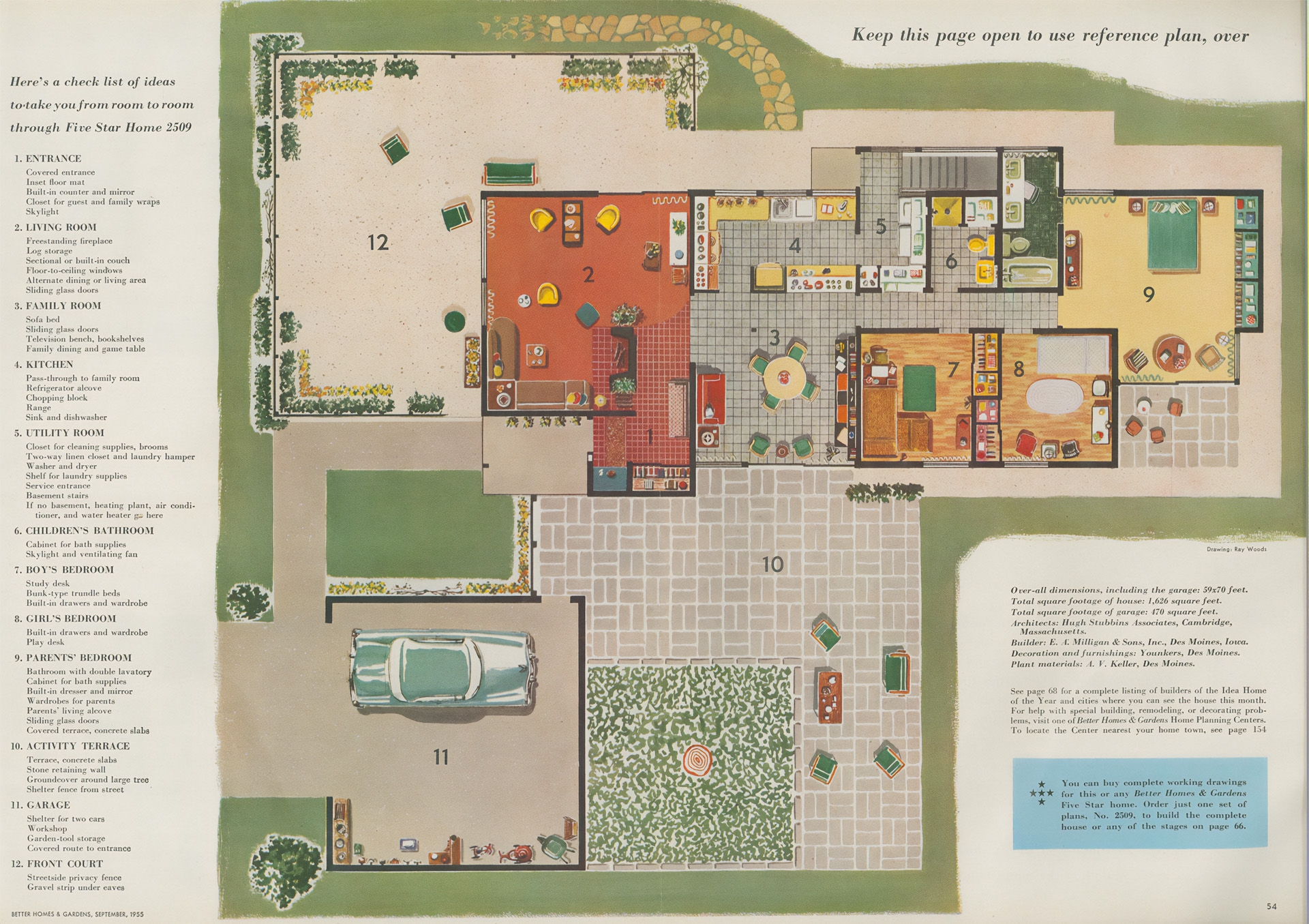

Naperville garnered national attention when this Charles Shiffler Sons home appeared in Better Homes and Gardens as the 1955 Idea Home of the Year.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

The Naperville of the mid-twentieth century was designed to be more than just a place where people lived. It was home to North Central College (NCC) and increasingly targeted businesses to relocate to the growing tech corridor along the East-West tollway. The combination of an increased residential population, a socially engaged college population, and the presence of national corporations put pressure on Naperville to embrace civil rights.

Naperville garnered national attention when this Charles Shiffler Sons home appeared in Better Homes and Gardens as the 1955 Idea Home of the Year.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

After World War II, students and community members challenged the discriminatory treatment of Black NCC students. Sundown practices prevented Black college students from comfortably traveling west of Main Street in the downtown. NCC students satirized that every time the college got a new Black student, the Naperville police got a new officer to follow them. Early desegregationDesegregation: The process of ending a policy of racial segregation. campaigns targeted barbershops, drug stores, and Centennial Beach. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at North Central College at the invitation of Rev. George St. Angelo, the school’s chaplain. King’s visit sparked an interest in civil rights that pushed students and faculty to travel to Selma and Chicago to protest for civil rights and to work in Naperville in the areas of employment and housing to create a more open community.

Naperville Sun photograph of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Arlo Schilling, president of North Central College, at November 21, 1960 luncheon. King told the crowd, "We have privilege of standing between two ages--the dying old and the emerging new.” The old world, defined by imperialism and segregation, would only yield to the new one with the rejection of bigotry and the promotion of understanding.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

The Naperville Human Relations Council, an independent group created in 1965 by the Naperville Council of Churches, worked to make Naperville more accepting of residents and workers of color. A 1968 survey by NCC students found that of 113 local businesses, only 11 employed Black workers, but 70 said they would hire qualified Black applicants. The report’s authors argued that housing discrimination was the primary reason why Black people did not work in Naperville. Most of Naperville’s Black workers lived in Aurora, Joliet, and Chicago—cities with established Black communities. They could not live nearby, so there was no point in applying. Even people who were employed locally could not find nearby housing. In 1967, only one of 225 Black employees at Argonne National Laboratories was able to live in surrounding DuPage County.

Rev. George St. Angelo served as chaplain at North Central College from 1955 until 1966. From that position he brought in speakers like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to campus in 1960 and accompanied students who traveled to Selma in 1965.

Courtesy of the North Central College Archives

In 1964, Bell Labs announced plans to open a new division in Naperville and worked with the City to attract the best scientists in the country. But in 1966, when two Black scientists were transferred to Naperville, realtors steered them away from the city. The Naperville Human Relations Council attempted to work with local realtors to show the couple houses, but their efforts failed. Working with the NAACP, they filed a complaint with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, demanding that their employer help them find housing in town. They had to fight for the right to live in the city where they worked.

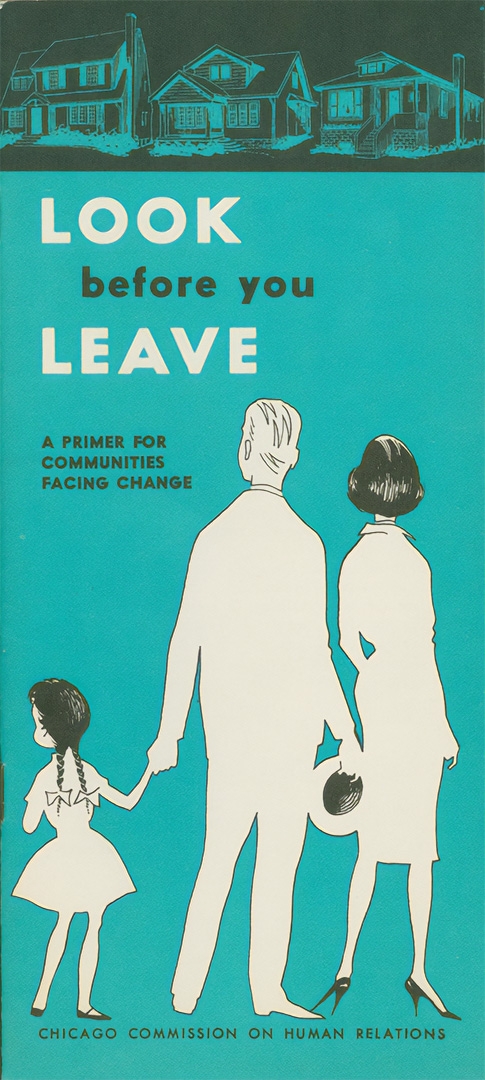

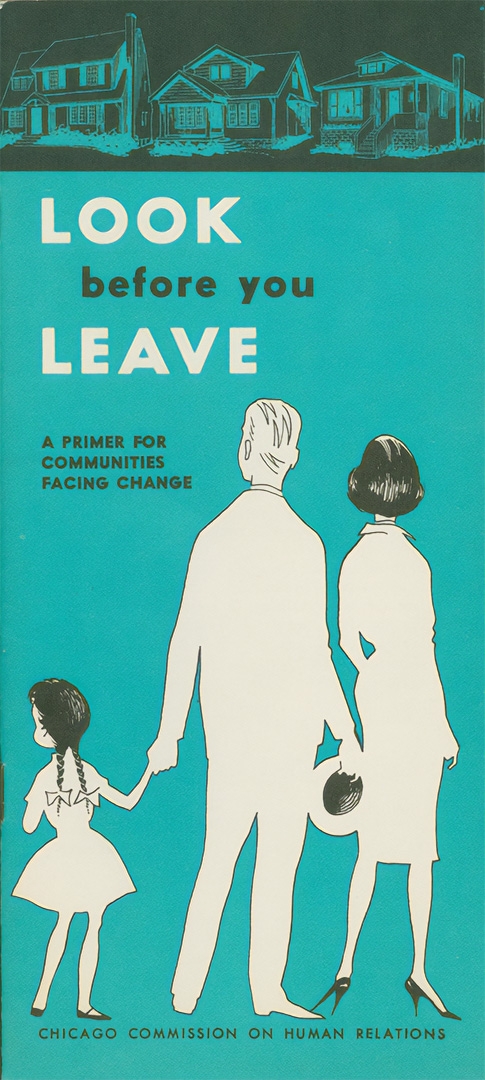

Naperville Human Relations Council member Mary Liz Burris collected materials that dealt with issues of housing and race and gave guidance to people working to address segregation and neighborhood change during the 1960s.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

By 1967, there was enough support for integration that Naperville activists began to push for an official human relations commission in city government. The effort failed. At a city council meeting, Commissioner John Zedrow recalled Naperville’s sundown customs of years prior: “I remember when a certain minority (Negroes) had to be out of town at sundown. I remember when they couldn't participate in our beach, when they couldn't go get a haircut.” His answer, the same as many in Naperville, was to let change happen at its own pace. Further arguing there was no need to change laws or ordinances when practices would naturally shift over time. Advocates for civil rights rejected this model and continued to demand that Naperville become accessible to all who wished to live there.

The Naperville Community Council appointed a Human Relations Study Group in 1964 “to study the organization and duties of a formal or informal human relations group and the advantages and disadvantages of such a group in Naperville.”

Courtesy of the North Central College Archives

The next battle was over fair housing (often called “open housing” in the period). Religious activists took the lead, framing the issue as one of personal morality—that racial integration was the right thing to do. Fair housing efforts were led by the Naperville Human Relations Council including Dr. Richard Eastman, Rev. Richard Tholin, Betty St. Angelo, and Mary Liz Burris. Eastman and Tholin were also connected with North Central College while Betty St. Angelo wrote publicly on behalf of Naperville Church Women United and Mary Liz Burris was active with the Naperville Human Relations Council. Their efforts provoked an intense public backlash. Defenders of segregation labeled ministers and professors as “outsiders” with no right to judge Naperville residents. Shifting tactics, activists presented fair housing as inevitable and framed the discussion around what would be in the best interest of Naperville homeowners. They argued that fair housing would help spur corporate recruitment and economic development and would also contain the rise of individual property taxes. A speaker at a November 1967 meeting of the Naperville Human Relations Council urged support for a fair housing ordinance, arguing that it would lead to economic, but not demographic change.

If Naperville should pass an open housing ordinance, nothing would happen tomorrow… Certainly there would be no great inundation of Negroes. No more than 60,000 of Chicago’s more than 1,000,000 Negroes could afford to live here. Few of those care to be the ones to enter an all-white community. If open occupancy is not achieved, however, industries considering moving from the central city will by-pass. Industrial parks will remain empty, and homeowners will get no relief from taxes.

—Speaker, Naperville Human Relations Council

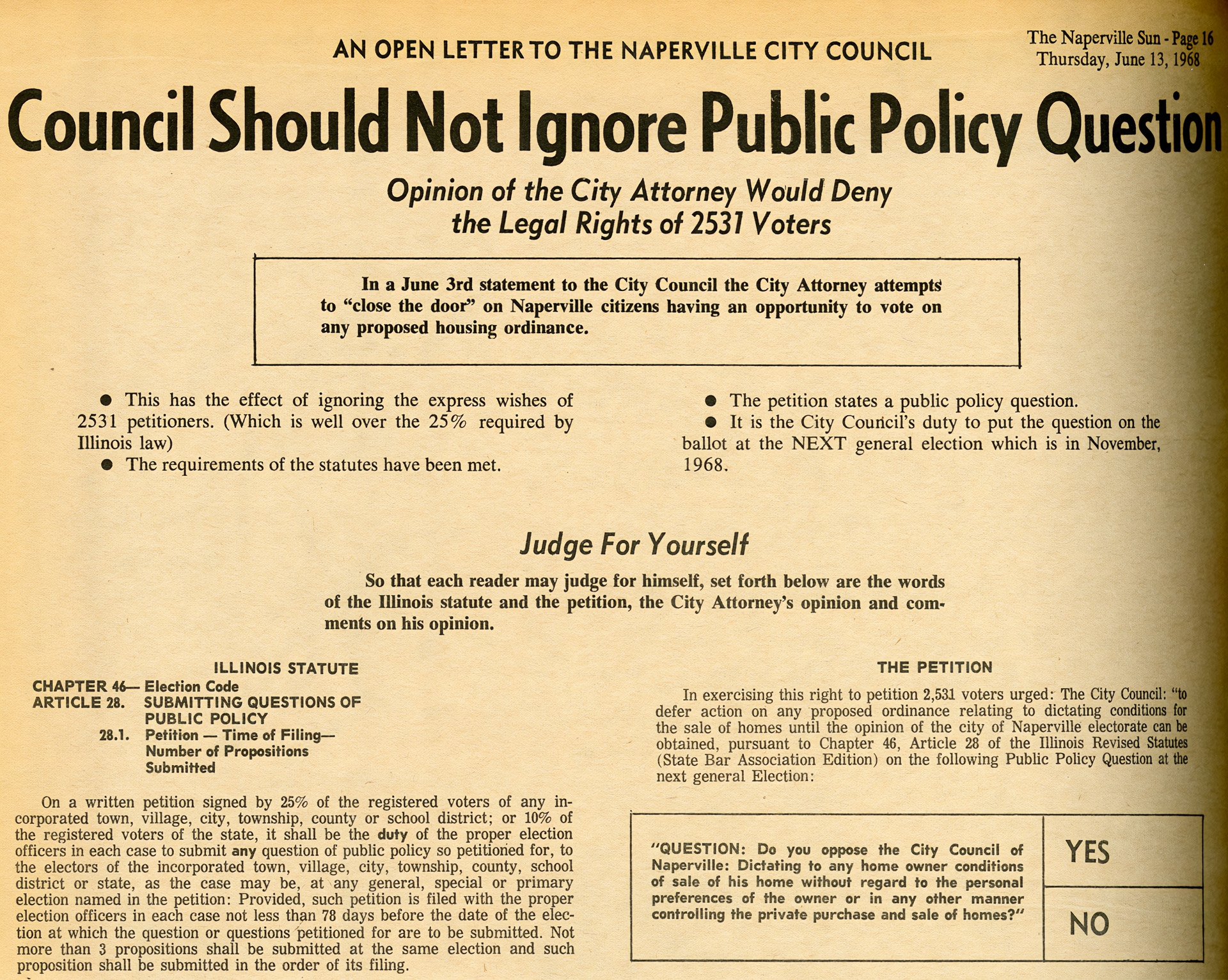

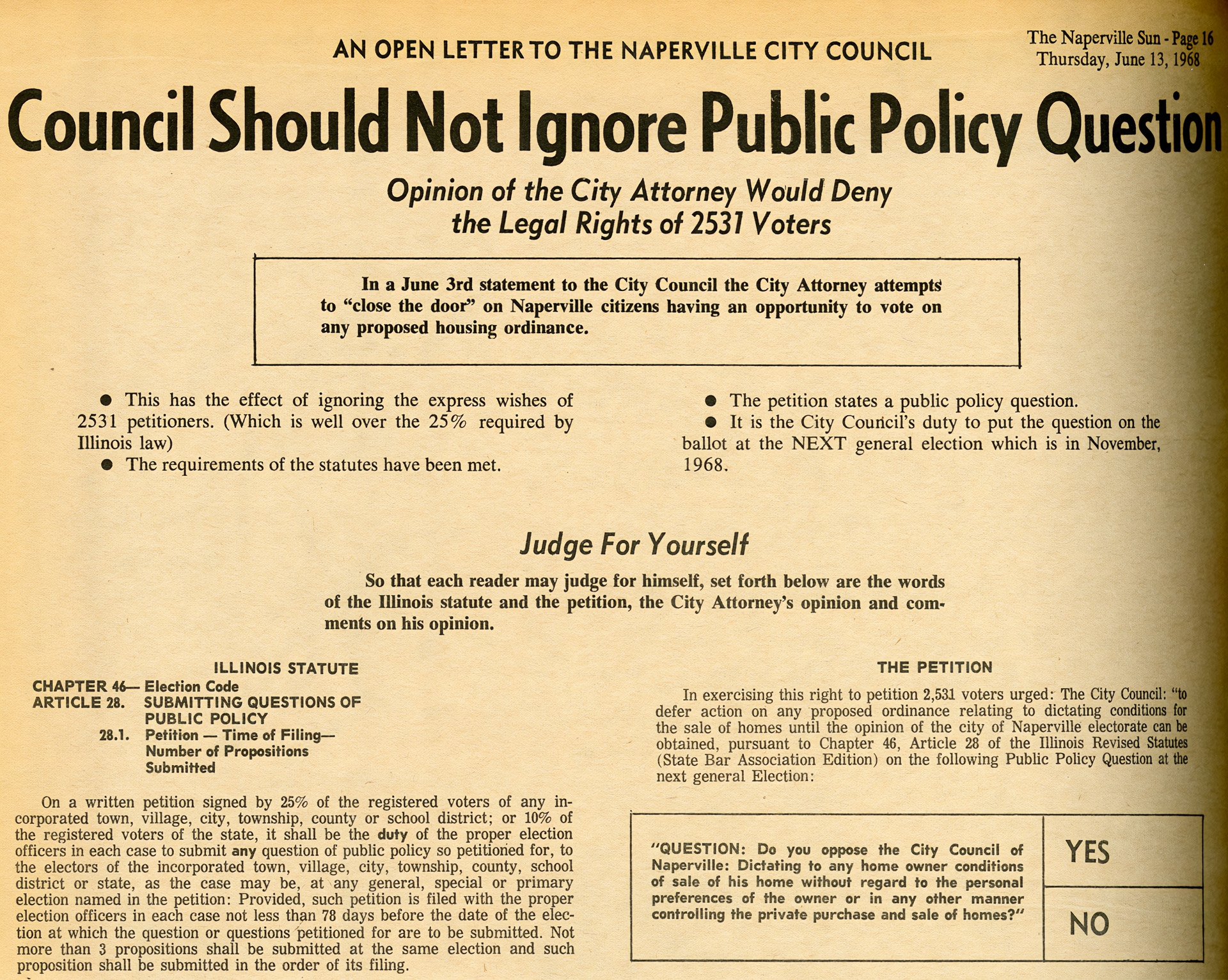

An open letter to City Council asking that the fair housing ordinance be placed on the ballot, published in Naperville Sun on June 13, 1968. The City Attorney rejected this petition and City Council voted 4-1 for fair housing on July 1, 1968.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

Opponents argued that fair housing violated their private property rights. In 1968, a community petition circulated to put a fair housing referendum on the next ballot, with the expectation that it would fail if put to community vote. National events soon overcame local debates. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., passage of a federal fair housing law, and the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Jones v. MayerJones v. Mayer, 1968: US Supreme Court decision that congress has the authority to regulate the sale of private property and bar housing discrimination based on the 13th Amendment. This allowed for federal action in private as well as public acts of discrimination. The ruling connected housing discrimination with the legacy of slavery and reinvigorated the Civil Rights Act of 1866 for the first time in a century. declaring that housing discrimination violated the 13th Amendment, pushed Naperville’s city council to adopt a fair housing ordinance in July 1968.

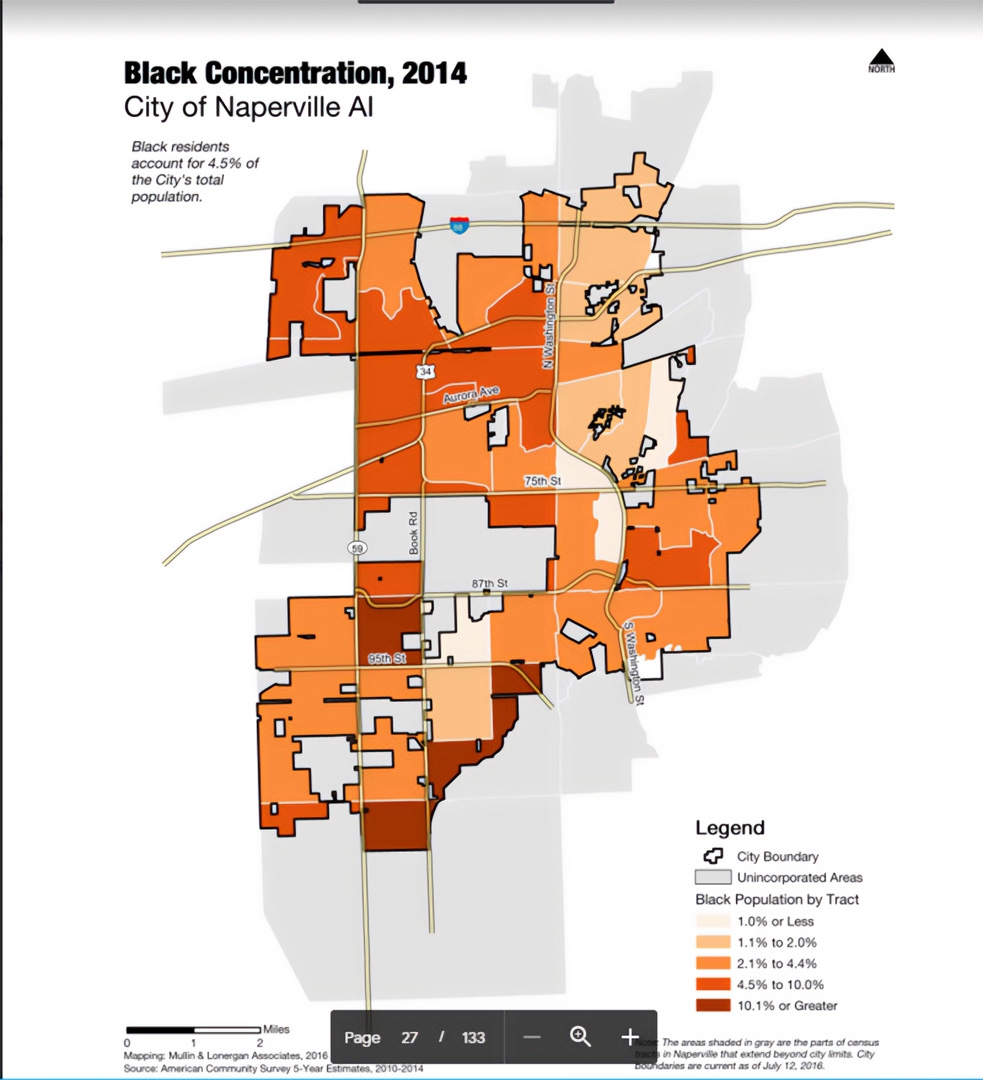

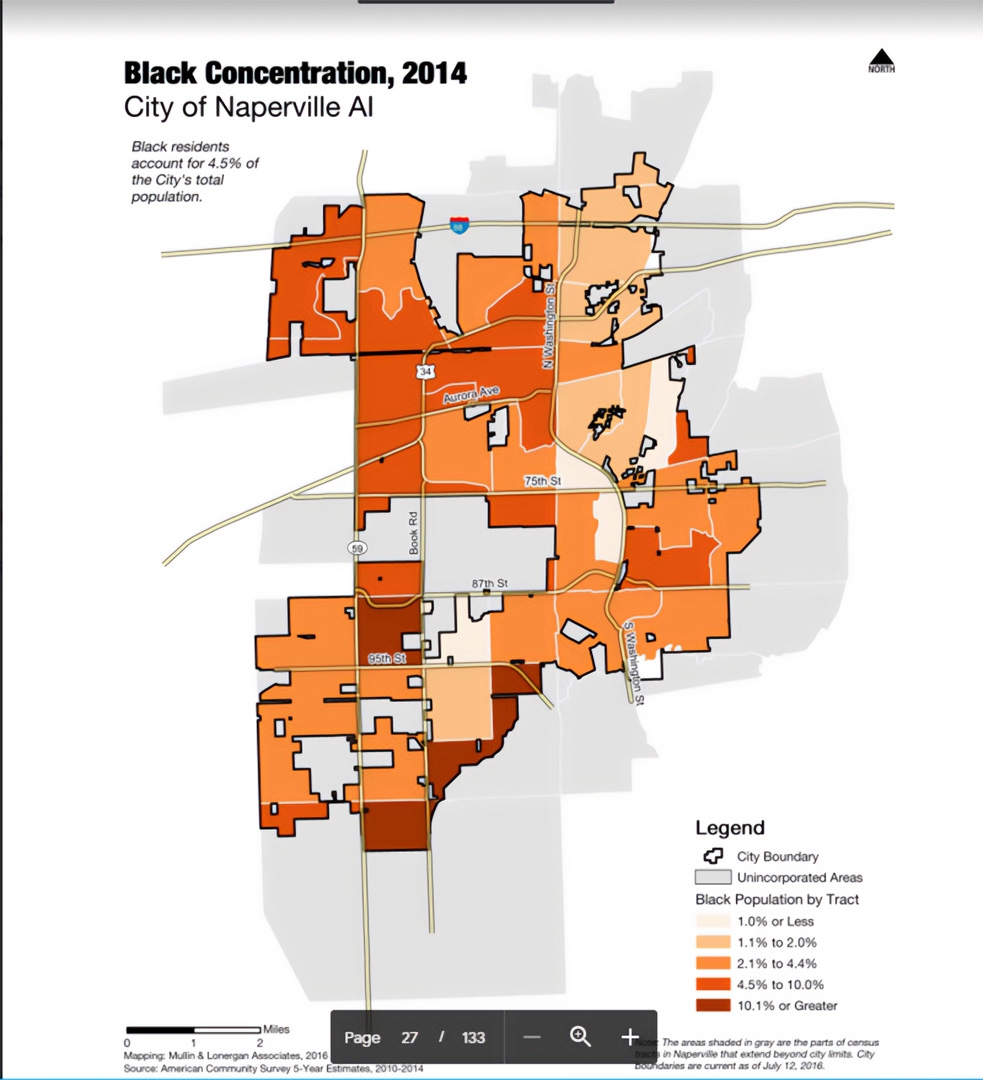

A map from the 2017 report on challenges for affordable housing in Naperville reveals a city still largely divided along racial and class lines.

Courtesy of the City of Naperville

You don't speak about the ugly race relations in the United States. This is exactly the issue that we have to talk about.

Historian

ViewHide Transcript

I'm going to tell a personal story. I grew up in Hollywood, California. My grandmother was in domestic service in Beverly Hills. Beverly Hills is a famous sundown town and she was an Irish Catholic who lived in Hollywood. I as a young man, and I probably was about 14, I started going to a Jewish deli out in Glendale, California, and I asked my father, I said, “You know, why do they call it Lily White Glendale?” And my father turned on me, I mean this is one of the kindest people on Earth, and he says “You know why!” and I said “I really don't know why. It seems like a lot to say, Lily White Glendale.” And he says “Well, you know why?” And he wouldn't really answer the question because you don't speak about the ugly race relations in the United States. This is something that you do not talk about. What do you do with this? Because you're told and you know, I'm obedient to my father as much as I could be. You don't speak about this. But this is exactly the issue that we have to talk about.

Naperville’s population doubled each decade from 1950 until 2000. The Naperville housing market reveals a complicated story about growing diversity in Naperville: while increased home values have added to the wealth and quality of life for many, the city has become increasingly unaffordable for low- and middle-income people. Contemporary housing debates largely focus on affordable housing. Individuals and organizations are now pushing for recognition of Naperville’s history as a sundown town. Community divisions around recent cases of racial and religious discrimination have brought negative attention to the city. A new generation of activists has facilitated discussions, called for new resolutions and government action to address discrimination, organized public protests, and celebrated Naperville’s diverse population in hopes of making the city more inclusive. Despite Naperville’s increasing diversity, racial justice and access to housing remain central to discussions of the city’s present and future.

So they saw a need to have an advocacy group that would represent their voice.

Community Leader

ViewHide Transcript

Last three years, I have been the chair of the Parent Diversity Advisory Council for District 204. So this organization started 16 years ago when Naperville started changing and we saw or they saw at that time, my kids weren't in school yet, that there were certain children that were being left behind and the achievement gap was starting to grow with our Black and our Hispanic populations.

So they saw a need to have an advocacy group that would represent their voice because they were still such a small minority at that time. So in first grade, that would be like 11 years ago or 10 years ago, when I started first grade with my son, my principal said, I think you would be the really good person to get involved in this group. And I started going to their meetings and I became our elementary school representative and started doing a lot of the first changes that you saw.

We were the first cultural night. I was able to talk to our art teacher to bring in Jaipur stamping into the curriculum of our elementary school. You know, we were able to do a lot. I also got a lot of pushback because it was change and it was, you know, so it was not any. I mean, there was one PTA meeting where the district brought their lawyers because it was about why are we making Jaipur block printing the same month as Halloween, when we can no longer celebrate Halloween in the schools and have costumes? So that became, and it wasn't, I wouldn't say that the intention was racist or but it was the change was too much.

Festivals, like the annual Holi celebration hosted by Simply Vedic in Naperville, provide opportunities to celebrate and share cultures.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

Grassroots organizations and interfaith groups have pushed for greater understanding of the issues and work to promote community dialogue.

It's not isolated. If an African American came forward every time they were discriminated against or someone who mistreated them. We would be doing that all day.

Community Leader

ViewHide Transcript

Chief Dial was coming into town, I think he came from Colorado, and I thought it was an opportunity to have conversations with the new person, right, who was coming into the new community and letting him know what is going on. Not getting the, you know, the whitewashed version of it or to say that it's cleaned up, I'm going to clean it up. And I'm not going to tell you the real truth. I'm going to tell you the truth I want you to hear. And so, what I wanted to do was sit down and talk to him and let him know, not the clean story, right? But the real story. And he welcomed me to come into his office. He hadn't been here long at all. Sat down and talk to him about it. And I said, It's not just me and my husband. You hear from friends and there were certain streets that were notorious where you get stopped on all the time and it's a profiling. And he made it known that's not what's going to happen while he's in charge. And so he started having these conversations with his officers, and he started to keep information about how many of the people that were being stopped, how many were African-American, right? So you have some evidence of that. And he started having these meetings with his officers, and I've been to meetings with his officers where we talked about race.

He invited me in to do that, which I thought was beautiful, to open the door for me to come in and have these conversations. At that time, I think there might have been one African-American on the force at that time, maybe one. And so I knew that he meant business, and I think I saw things change once Chief Dial was here, and once he came to town. I saw things change. Now, it didn't, wasn't perfect, right? And it still isn't, but it improved. He had an advisory board. He asked me to sit on an advisory board because he wanted to hear that, he needed that diversity and wanted that diversity. And I can talk about my community where maybe the people that were around the table couldn't. I could give you the stories about my community that you may not know about, but these things were happening then. They're happening now. It's not isolated.

If an African-American came forward every time they were discriminated against or someone who mistreated them. We would be doing that all day. We wouldn't have time to do anything else. So that's our life. I wish it were different, but that's our life. And so, you know, I tell myself and I told someone else this at a meeting. This person was running a group about race. This person was in charge of a group that were discussing race. And I said, You know, when I when I leave my home in Naperville, when I leave my home, I open my door and I go out. I'm going out into a world where I have to be... I feel like I have to be armed and aware of my surroundings of everything because it's not about crime in Naperville, it's about the discrimination, the racism.

The City of Naperville adopted a new mission statement in 2019, specifically adding the clause “creating an inclusive community that values diversity.” In 2021, the city hired its first Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Manager who works directly with the Human Rights and Fair Housing Commission to promote equal opportunity, including fair housing.