Local Spotlight

West Hartford, Connecticut

Courtesy of the Connecticut State Library

Community Profile

- Community: West Hartford, 1679

- County: Hartford

- State: CT

- Type: Suburb

- Metro: Hartford

West Hartford is the ancestral homelands of the Sicaog, a Native American people who were part of the Algonquian confederation. The first European settlers in West Hartford were of English descent who settled in 1679 and brought enslaved people with them. In 1783, Connecticut’s Gradual Emancipation Act lessened the number of enslaved people in the state, but slavery was not officially outlawed until 1848. Census records indicate that West Hartford had a small Black American population (less than 2% of the population) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An influx of immigrants to Hartford at the turn of the 20th century led to a population boom in West Hartford, as residents moved from the city to the growing suburb. Through the early to mid-20th century, the population was 98% White. Today, the White population continues to be the most prevalent accounting for 73% of the population.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 71%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $334,300

- Median Gross Rent: $1,325

- Median Income: $104,281

- Poverty Level: 6.4%

- High School (ages 25+): 94.4%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 64.7%

Discrimination by Design

Discriminatory real estate practices played a defining role in the growth of West Hartford, CT over the past century. To Black and Jewish residents deemed “inharmonious” or “undesirable,” West Hartford’s evolution was shaped by overt and subtle discrimination. West Hartford’s history of racial segregation was the result of racism and religious prejudice, reinforced by restrictive covenantsRestrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group., realtor steeringSteering (real estate steering): Steering is the practice by real estate agents or brokers of limiting a purchaser’s housing options based on one of the protected characteristics under the Fair Housing Act, including race, color, religion, gender, disability, familial status, or national origin. It manifests itself through one-on-one conversations, limiting access to available properties, or providing false information about a property listing., and zoningZoning: A tool of city planning where cities are divided into specific zones with requirements for new development that set the zones apart from one another. Common zones are residential, business, and manufacturing/industry that can also include differentiation with zones for single-family homes or multi-family units among others. laws that targeted Black and Jewish residents.

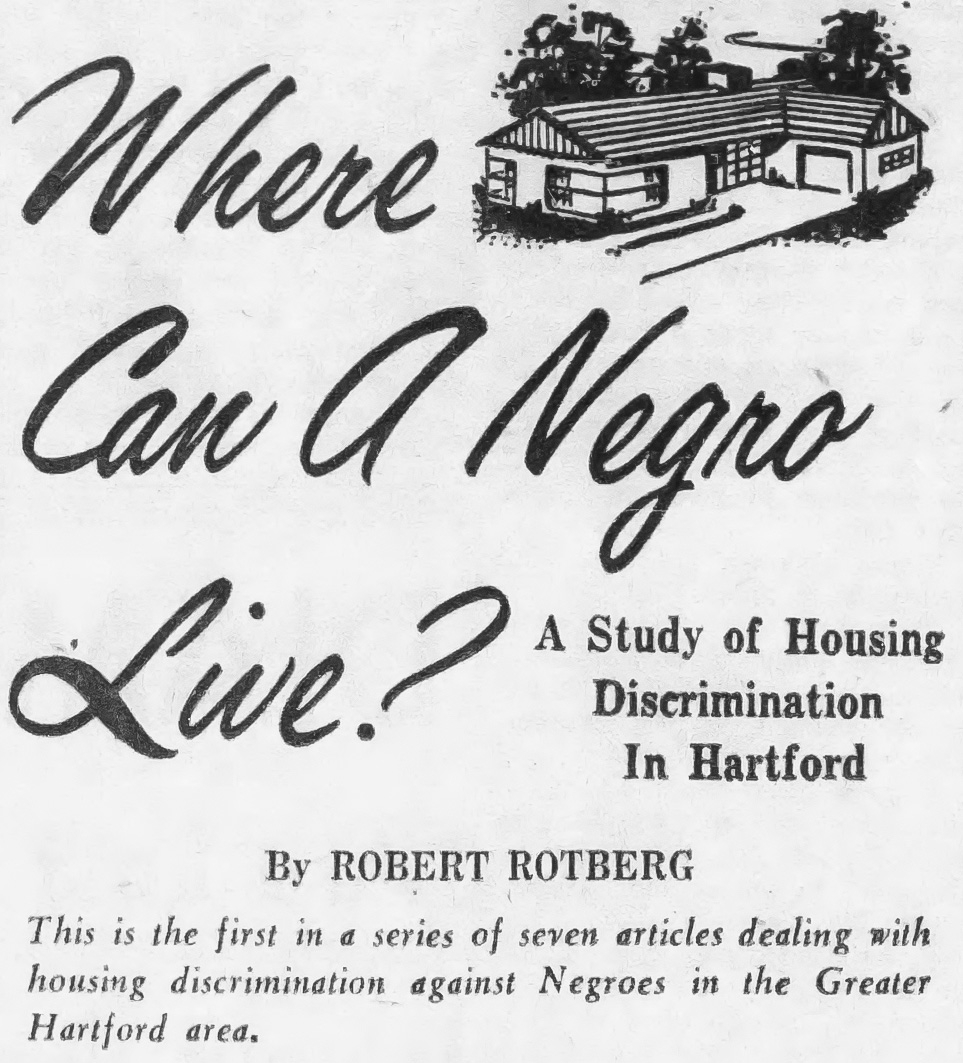

Journalist Robert Rotberg published a series of seven articles in the Hartford Courant under the title "Where Can a Negro Live?" about housing discrimination against African Americans in the Greater Hartford area. In this article, the first in the series, Rotberg calls out housing discrimination as the "last stronghold of prejudice in the urban North."

© Hartford Courant. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

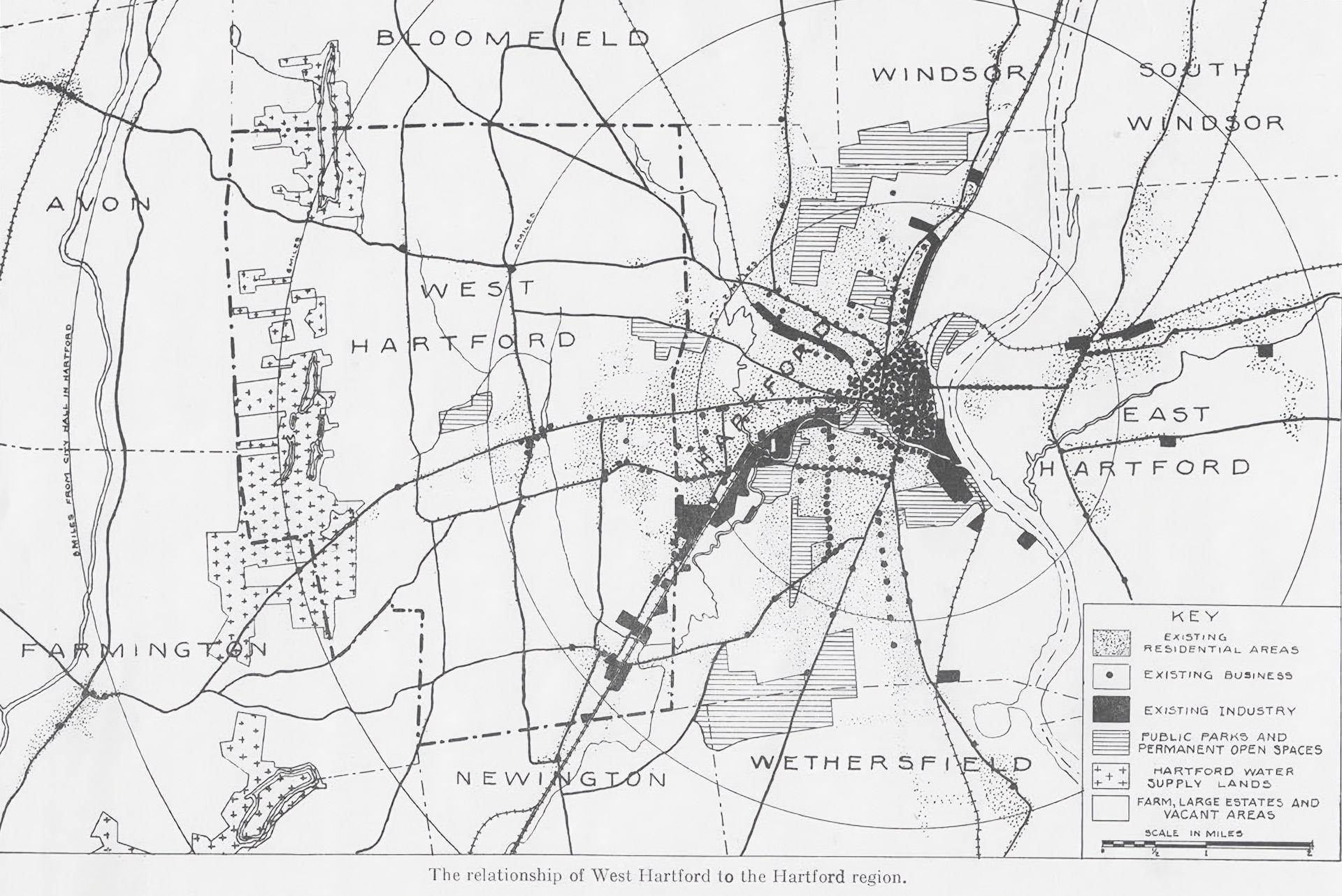

In the 1890s, the City of Hartford was bursting out of its limits. Wealthy residents, many in the insurance industry, moved to West Hartford’s east end, where an electric trolley line to downtown Hartford offered the convenience of easy travel to the city for work. Those who were welcome and could afford it lived in quiet pastoral neighborhoods outside the city. Over time, the ease of transit contributed to the rapid conversion of farmland into residential developments.

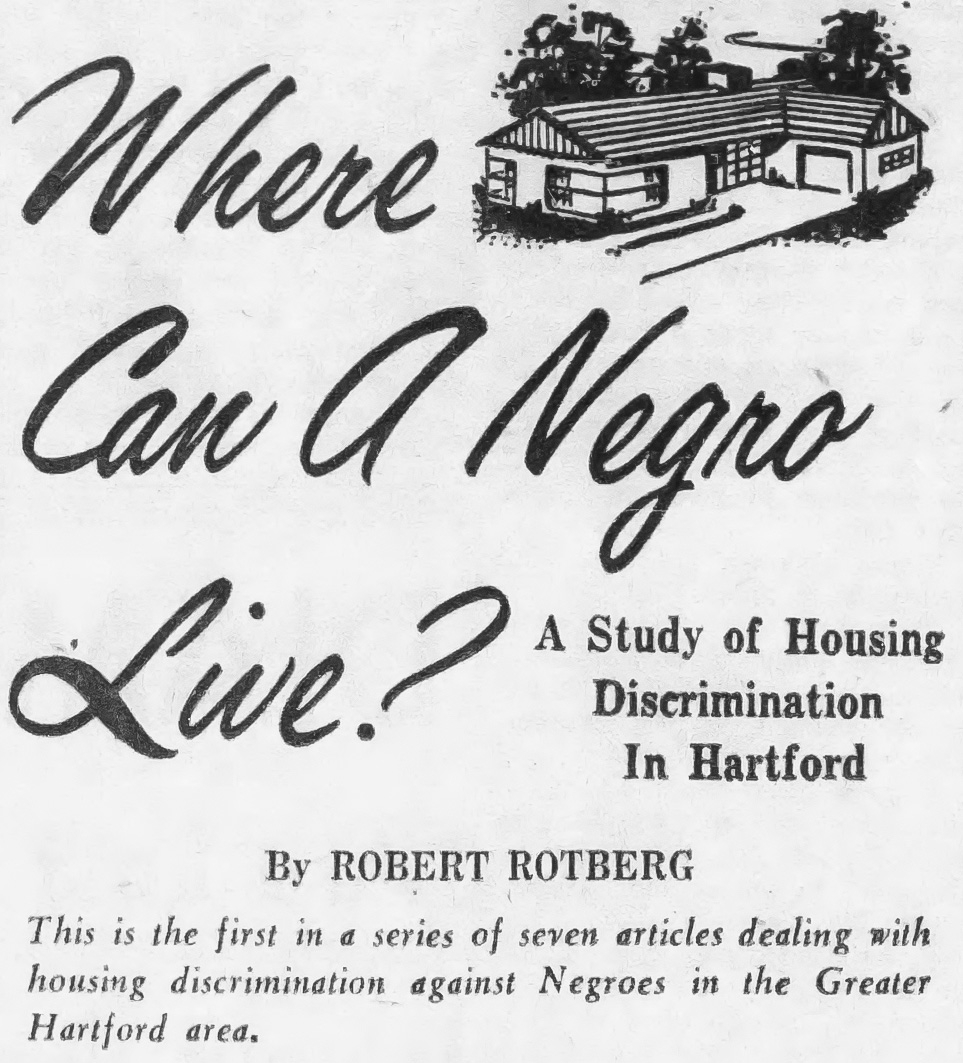

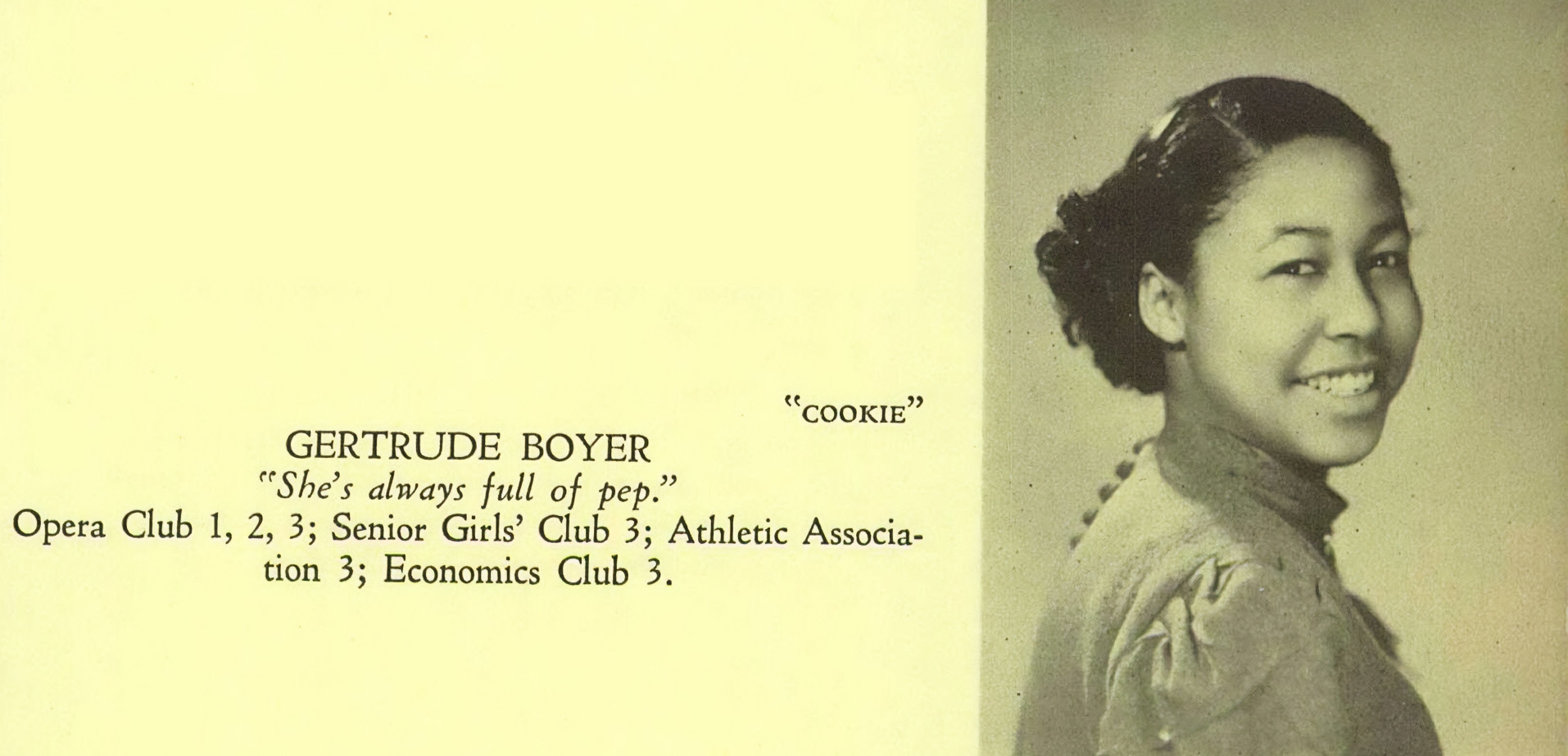

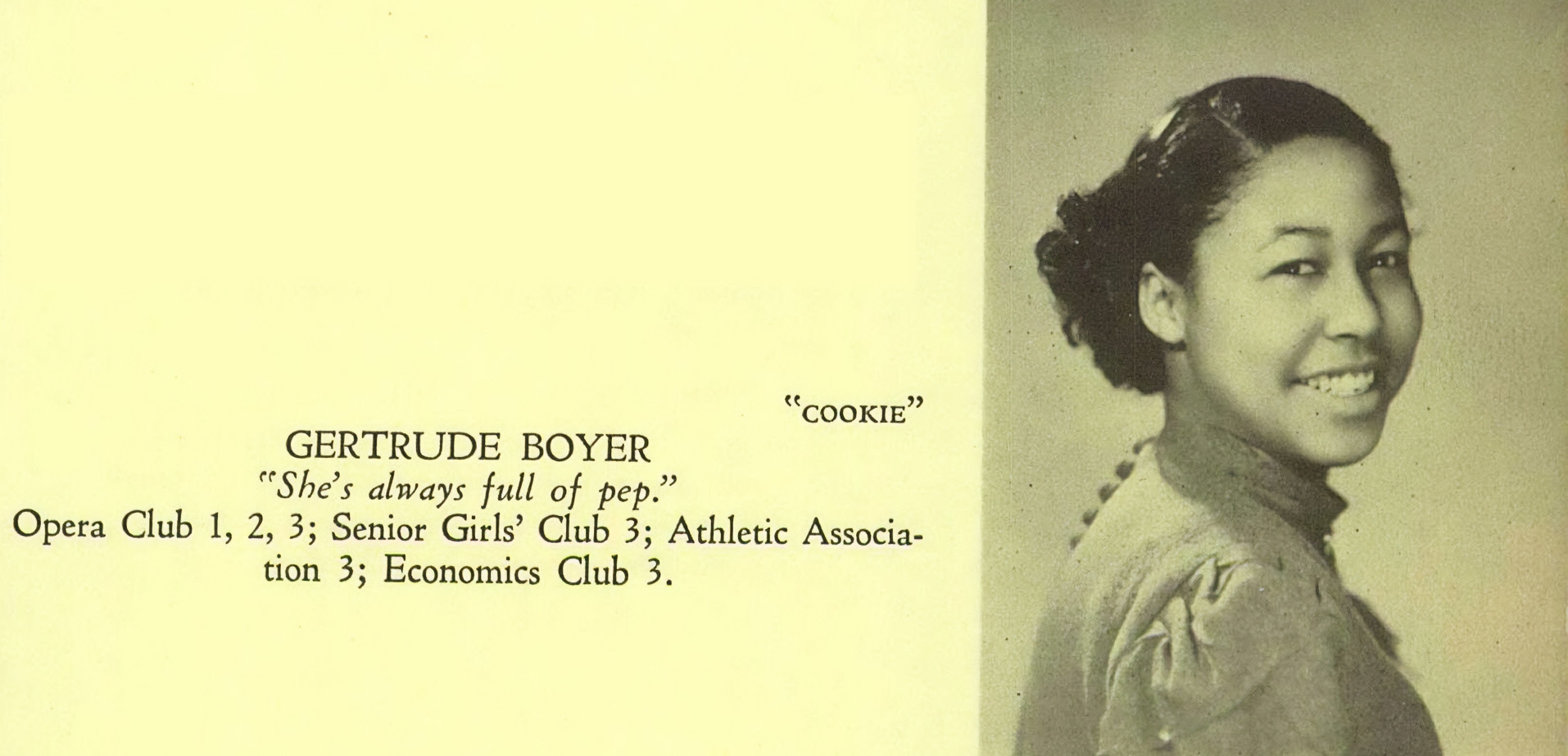

Gertrude Boyer Blanks was the first Black American student to graduate from West Hartford’s William H. Hall High School in 1938. As one of the few Black students in West Hartford at the time, Blanks endured nine years of being laughed at, punched, kicked, and once - blocked from entering school by classmates – with determination and forbearance taught to her by her grandmother. She recalled that her grandmother told her to: “Grit your teeth. Make up your mind that you are not going to answer. You're not going to get down to where they are.”

Courtesy of the West Hartford Public Library

Black people had been in West Hartford since its founding, when they typically arrived by force in enslavement or servitude. Throughout the nineteenth century, a small number of Black families lived in West Hartford, and some eventually owned property. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Black residents most frequently lived in White households where they worked as domestic laborers. In 1930, 129 Black people lived in West Hartford. Of these, only 30 lived in a household headed by a Black person.

George Pine lived in West Hartford and worked odd jobs, as a jack-of-all-trades. In this undated photograph, he rests on steps in the center of town.

Courtesy of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

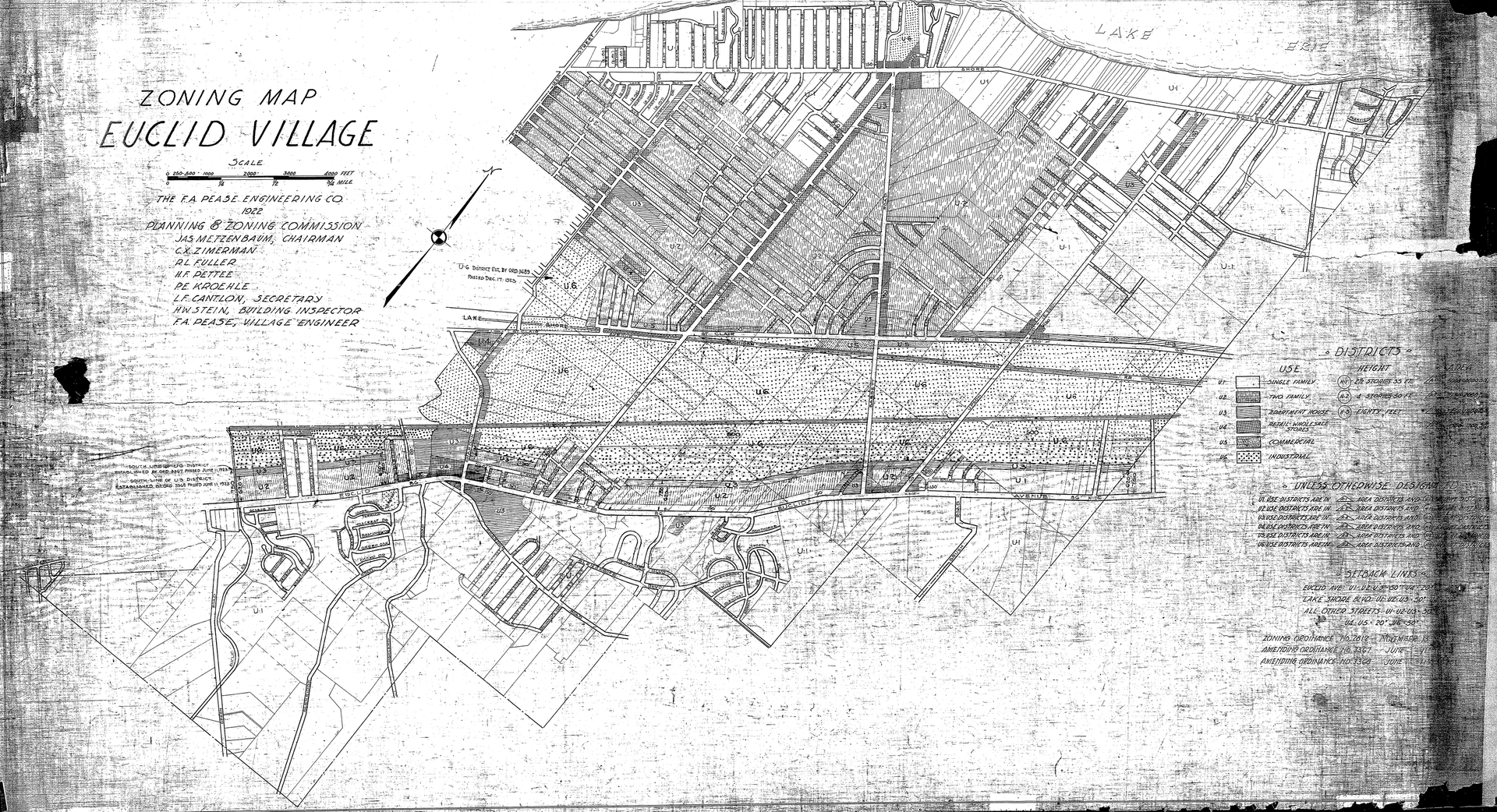

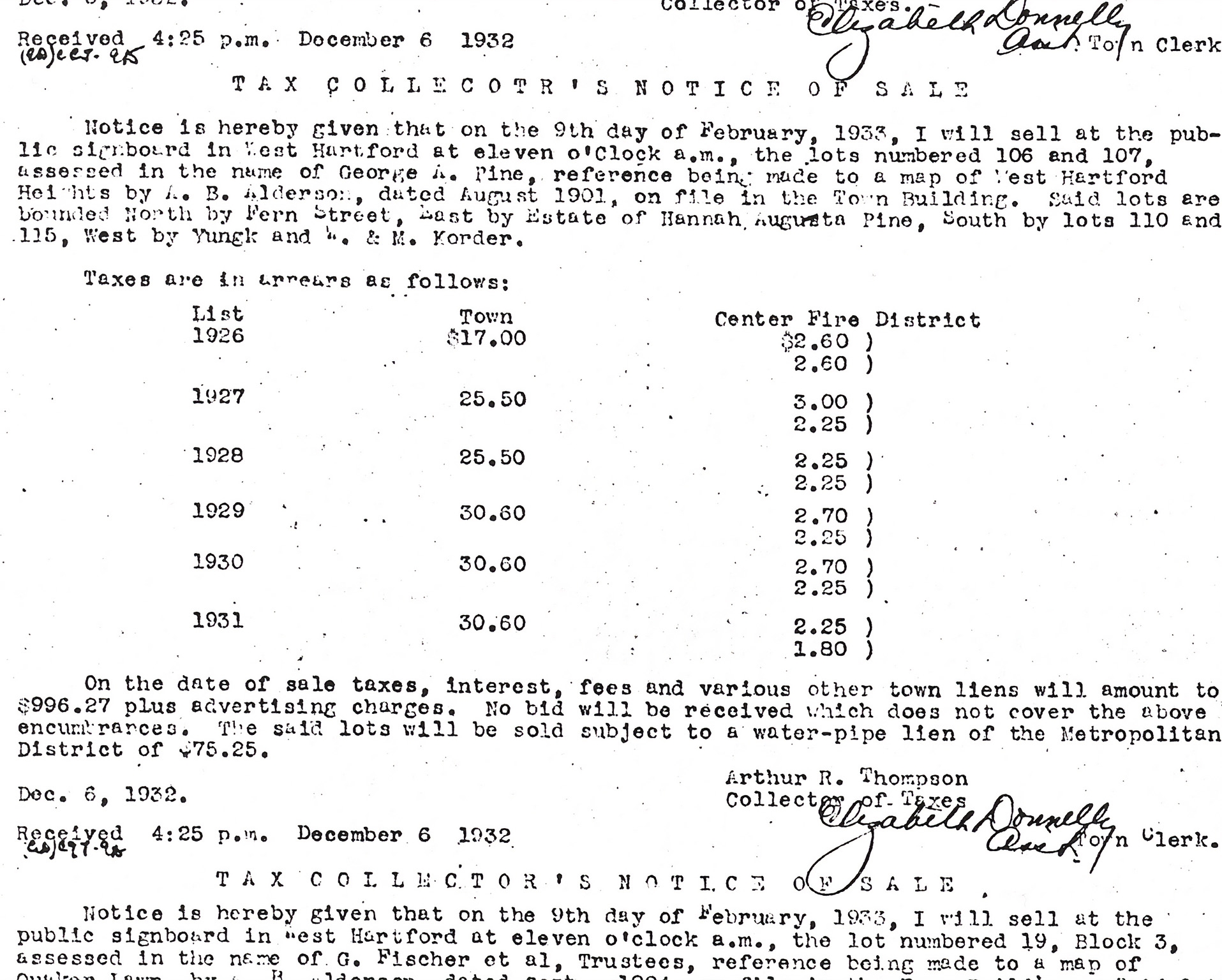

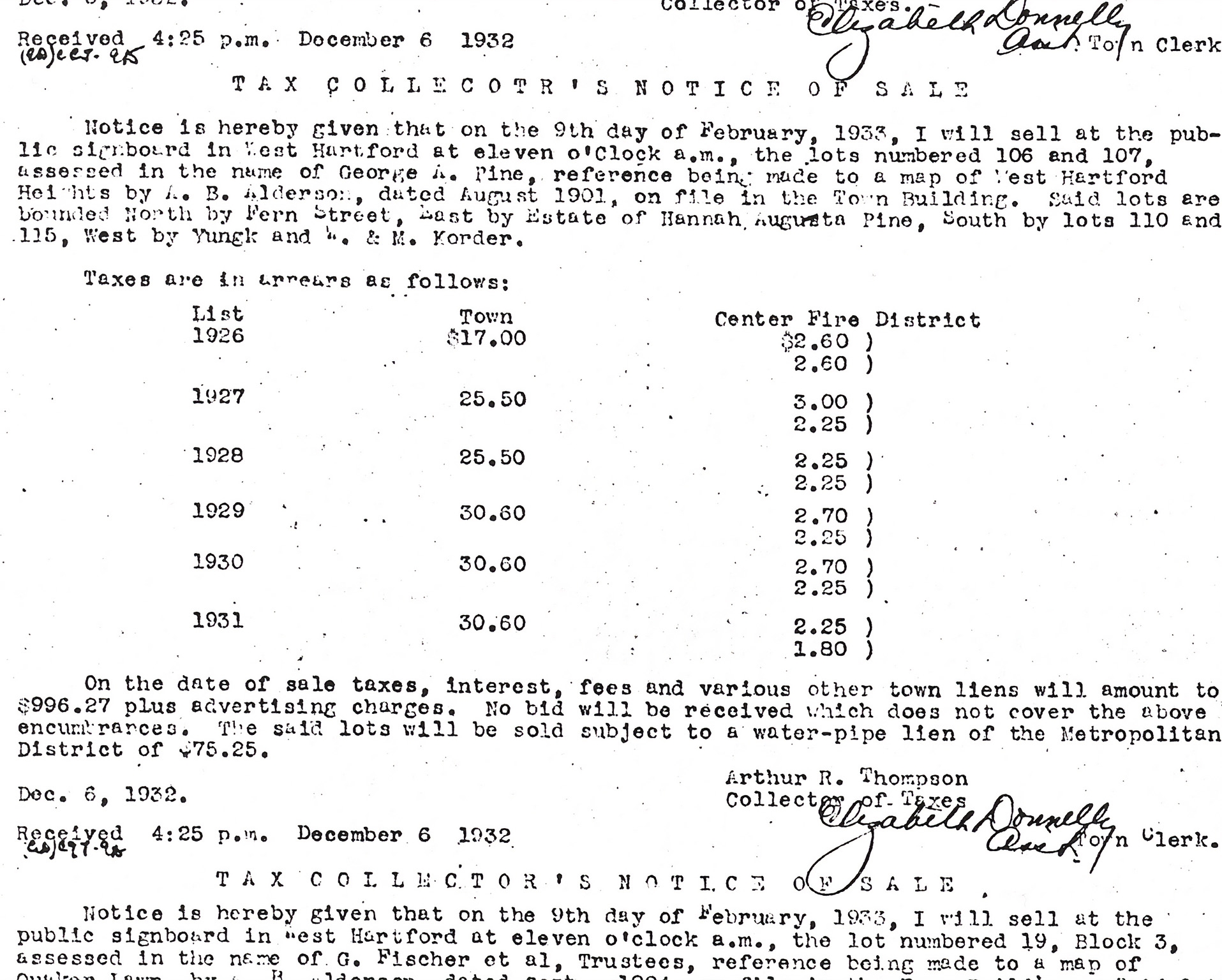

George Augustus Pine, born in West Hartford in 1876, was a homeowner living at the corner of North Main Street and Fern Street. After the death of his mother in the 1920s, George lost his family home and two lots of land, selling one and losing the other to unpaid property taxes. The Pine family’s loss coincided with zoning regulations enacted in 1924, the first of their kind in Connecticut. At that time, the town was divided into sections with specific restrictions on land use and lot size.

But in fact, what this zoning did was, its essence, was exclusionary.

Historian

ViewHide Transcript

While Blacks made up probably about 5% of the population here in the 18th century, it had really declined by the beginning of the 20th century. I think we have one statistic that says 0.5%. And I think that's not by chance. I think it became very difficult for Blacks to live here and to survive here. And that pattern really continues. In 1919-1920, West Hartford becomes the first town in Connecticut to have a town council-manager form of government. So it was this idea that you would have a professional run the town, and it led to the first zoning practices in town, which the zoning plan, first zoning plan was in 1924.

And you know, I think a lot of people see zoning as kind of benign. And as a teacher, I would say I always taught it as, it was a way to keep residential and industrial areas separate. But in fact, what this zoning did was in its essence, was exclusionary. Because it said, you need to have two-acre lots here and we need one-acre lots here and we can control multifamily housing. And so West Hartford definitely had the reputation of being a tony, a wealthy suburb in the 1920s and really into the 1930s. And there's this really incredible statistic from 1930 that shows that there were about 130 Black people who lived in town and 100 of them lived in the homes of White people.

So only about 30 of them were living independently here. And if you compare that to what was happening in Bloomfield, you have many more independent, people living independently. And so, you know, it was not a friendly place. If you were African-American, it was... it seemed tough to live here, at least extrapolating from the statistics. And in research, we've found that, you know, while the zoning is one factor, we find restrictive covenants. We find a fight against federal housing during World War II that are specific ways the town and developers acted against having Blacks live in the town.

Along with these changes came higher property tax rates. The new zoning plans made homeownership for low-income families, like the Pines, virtually impossible. Combined with other exclusionary factors like redliningRedlining: Redlining is the practice of denying mortgage loans to people living in neighborhoods determined to be financially risky. The name comes from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which during the New Deal commissioned maps that color coded neighborhoods from Green (Best), Blue (Still Desirable), Yellow (Declining), and Red (Hazardous). It was virtually impossible to get a loan in a red area and almost every Black neighborhood was denoted as red. and restrictive covenants, West Hartford drove out longtime Black residents and prevented new Black families from moving in.

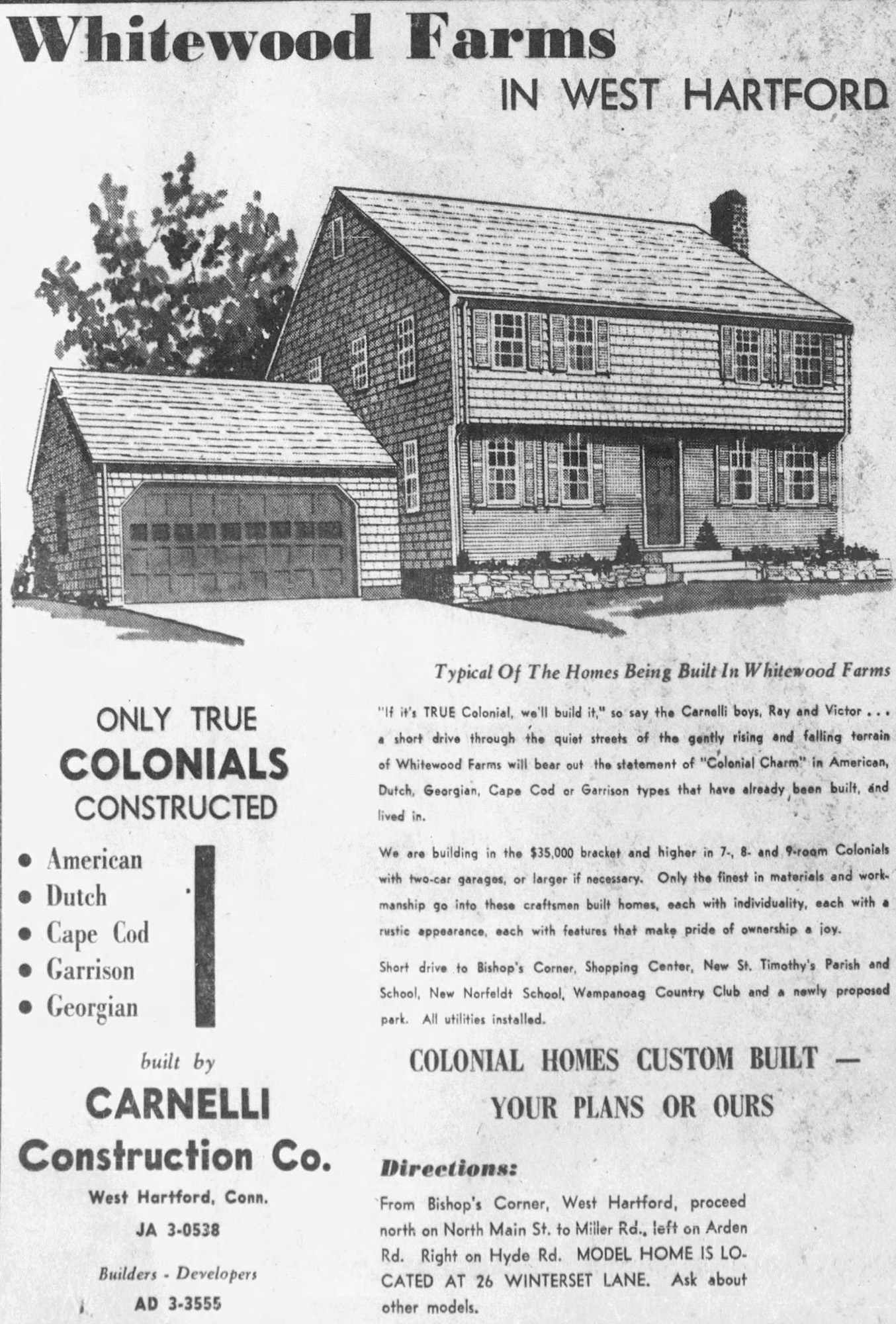

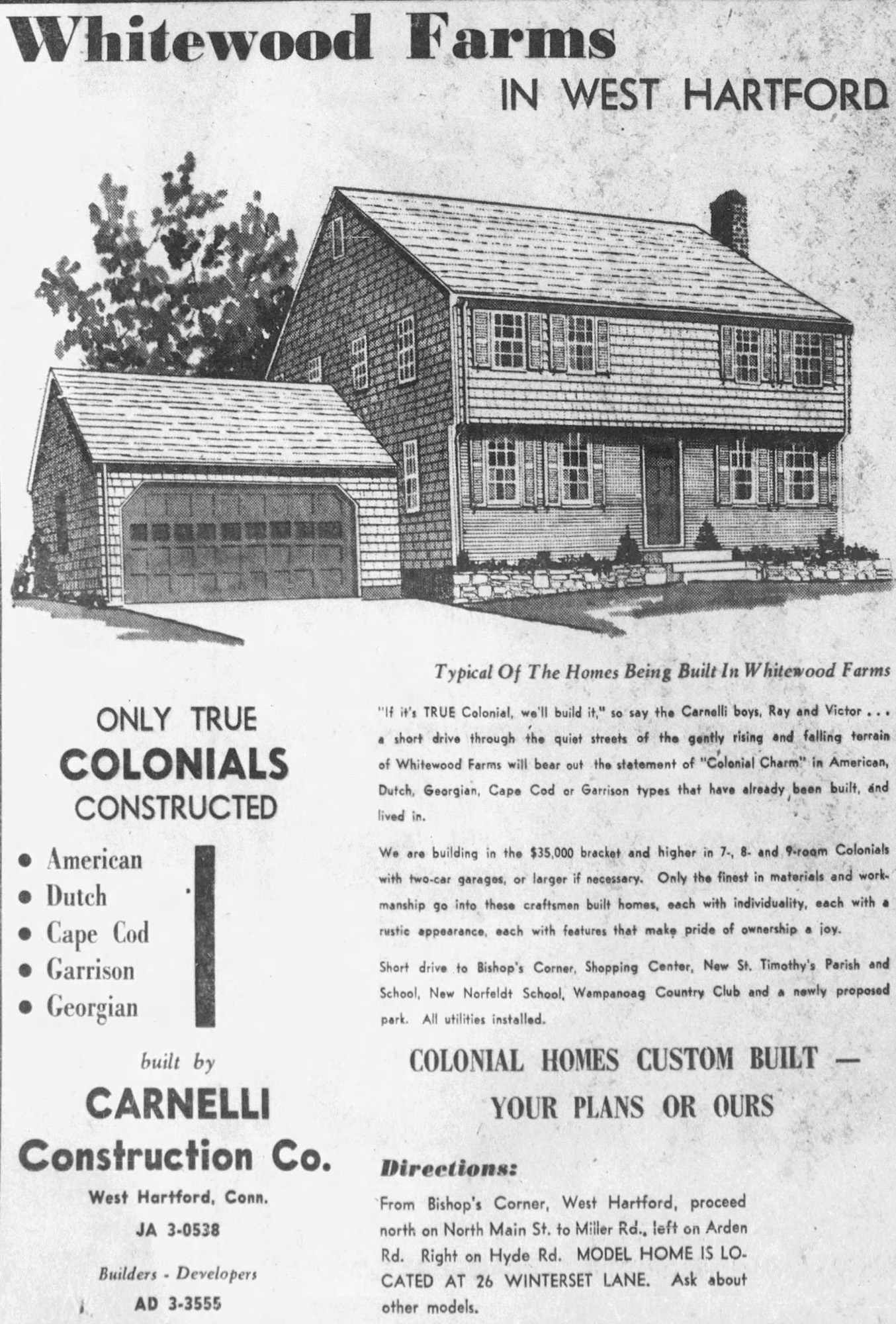

Brothers Raymond and Victor Carnelli's construction company developed hundreds of West Hartford houses between 1945 and 1970. Whitewood Farms showcases the subtlety of steering, encouraging Christian buyers to consider these homes, rather than Jewish home buyers or people of color.

© Hartford Courant. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

In the 1940s, five West Hartford developments added racially restrictive covenants on the titles to their properties. All featured the same clause: “No persons of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race employed by an owner or tenant.”

Tax Collector's Notice of Sale dated December 6, 1932 for George Pine's property.

Courtesy of Land Records, West Hartford, CT

Until 1948, when the US Supreme Court case Shelley v. KramerShelley v. Kramer, 1948: A US Supreme Court decision that ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. It did not remove them from property deeds and many remain on deeds to this day. ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable, White residents of West Hartford and similar communities throughout the United States had the right to sue for the removal of Black renters or homebuyers.

Built in 1943 as public housing for WWII workers, by September of that year only 20 out of 300 possible units were occupied. In a 1943 newspaper article, it is noted that “From an esthetic standpoint, the housing project on Oakwood Avenue couldn’t exactly be called a homeowner’s paradise.” With the threat of Black American workers moving into the units, the few occupants living at Oakwood Acres threatened to move out if Black Americans moved in.

Courtesy of the Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

The story of Oakwood Acres, a 1943 public housing development for war-worker families, spotlighted racism in West Hartford. When the town received federal subsidies for the construction of Oakwood Acres, White residents and officials were concerned about who would live there. Homeowners living near Oakwood Acres were quoted in the Metropolitan News as “alarmed” and “horrified” at the idea of “Negroes” living in their neighborhood. The paper warned of “an infiltration,” and reported that the prevailing sentiment among community homeowners was “We don't want them here.” West Hartford officials agreed to the construction after assurances that the housing would be temporary, only for the duration of the war. During a time of intense housing need, only 20 of 300 units were occupied in Oakwood Acres. Federal officials stepped in to prevent the exclusion of Black residents, but local officials found a loophole: to accept only those Black workers already employed in essential West Hartford industries. Only six Black families were eligible. Knowing that they were not welcome, none of the approved Black essential workers attempted to live there, effectively making Oakwood Acres a “Whites-only” development.

Homeowners living near Oakwood Acres were quoted in a 1943 issue of The Metropolitan News as being “alarmed” and “horrified” at the idea of “Negroes” living in their neighborhood. The paper itself described the situation in harsh, racist language, calling it an “infiltration,” and reported the prevailing sentiment among community homeowners as being: “We don't want them here.”

Courtesy of the West Hartford Public Library

White West Hartford residents wanted Oakwood Acres demolished at the end of the war. But returning veterans faced a lack of affordable housing, so these units remained in use and there were long waiting lists to get in. By 1951, local homeowners again pressured the town to tear down the development. Oakwood Acres was razed in 1956.

In an article in West Hartford News from 1973, Olivia Shelton recalled the “pettiness” of town residents. Real estate agents were known to scare off Black Americans from buying in certain neighborhoods by falsely claiming that there was a termite problem, or water in the basement. Shelton was so upset by the injustices that she sometimes would attend real estate open houses with her family “just for meanness and devilment … to scare the people.”

Courtesy of The McAuley, West Hartford, CT

In West Hartford, Black residents encountered acts of hate, prejudice, and racism. Olivia Shelton moved to West Hartford with her husband and two sons in 1959. Shortly after settling in, she found a note in her mailbox saying: “Get out of here, you black bastards, while you still can.” Later, at the age of 87, Shelton recalled that she was just happy she got to the note before her sons did. In a 1973 article in West Hartford News, Shelton recalled the “pettiness” of town residents. Real estate agents were known to steer Black homebuyers away from certain neighborhoods by falsely claiming that there was a termite problem or water in the basement. Shelton was so upset by the injustices that she sometimes attended real estate open houses with her family “just for meanness and devilment … to scare the people.”

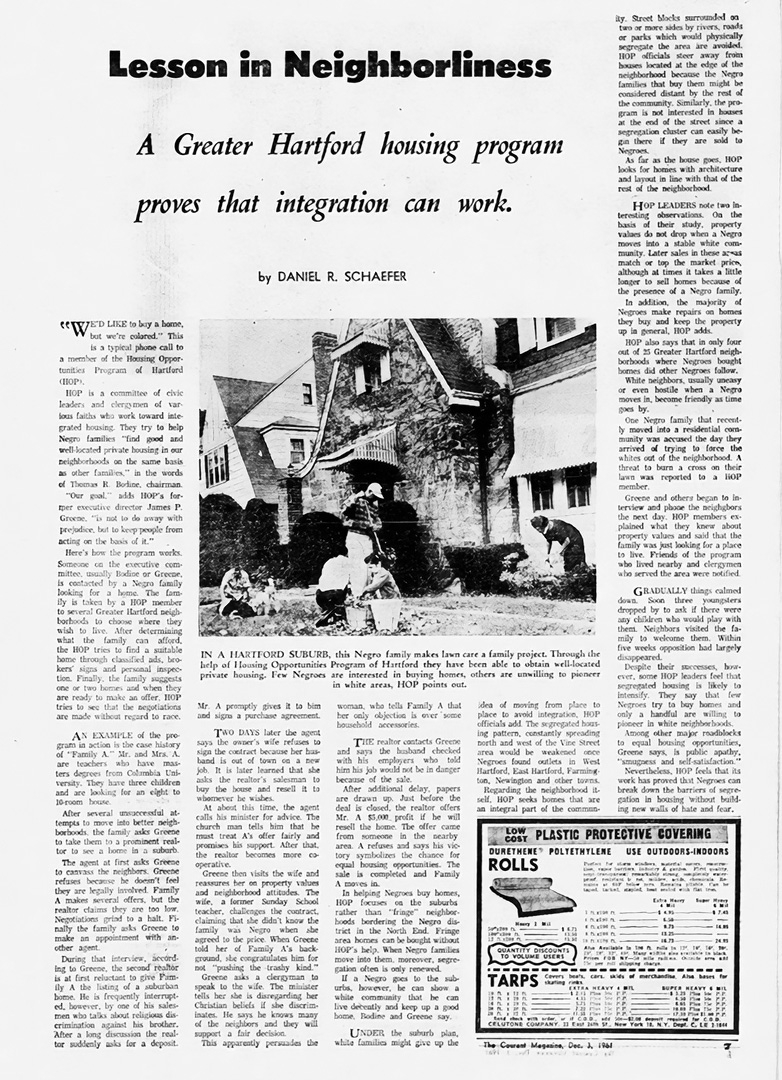

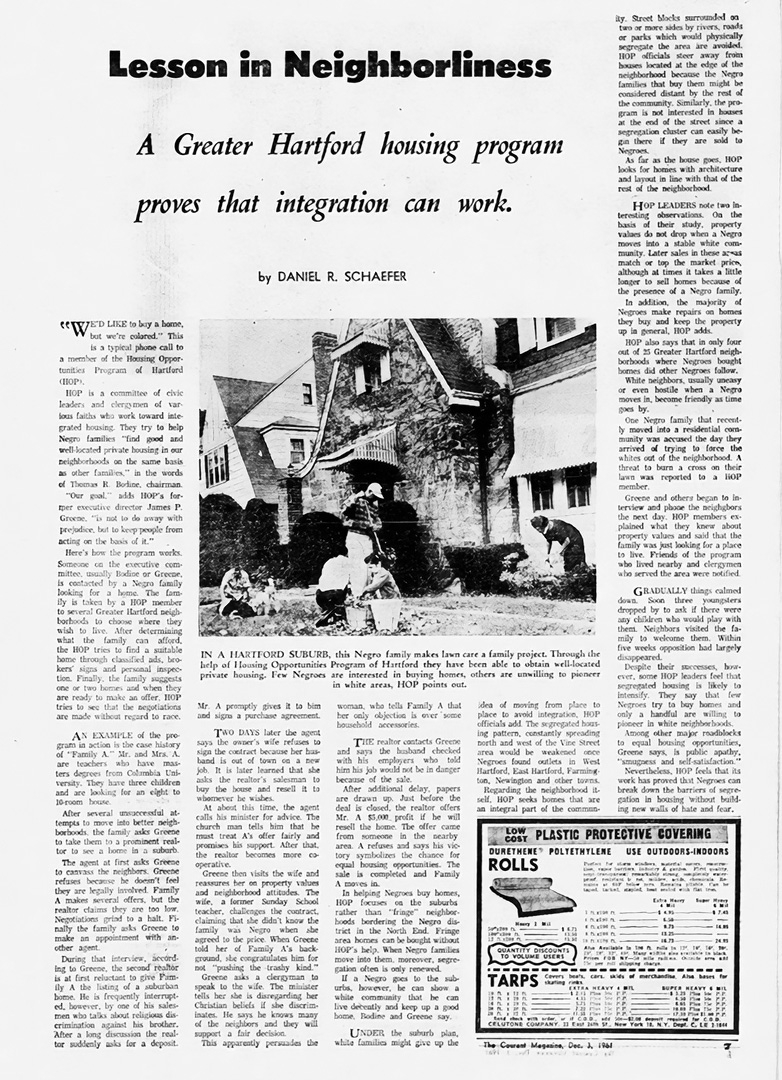

A housing program in Greater Hartford known as HOP (Housing Opportunities of Hartford) worked to find integrated housing for families. The program consisted of a committee of civic leaders and clergymen from different faiths who worked together to help "Negro families find good and well located private housing in our neighborhoods on the same basis as other families. The leaders of HOP feel that their work shows that it is possible to break down the barriers of segregation without building new walls of hate and fear."

© Hartford Courant. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Increasingly, realtors steered potential Black residents north toward the adjoining town of Bloomfield. Realtors also used steering to limit the housing choices of Jewish homebuyers. When Congregation Beth Israel, West Hartford’s first synagogue, was built in 1933, an enclave of Jews resided in the community. After World War II, more Jewish families began moving to West Hartford as part of White flight from Hartford. Realtors directed potential Jewish homebuyers to certain neighborhoods while Christians were directed to others. In a 1993 newspaper article, Linda Hirsh, a former staff writer for the Hartford Courant, described her family’s experience looking for a house in the 1970s:

“A realtor helping my family find a home in West Hartford spread a map of the town on the floor. He proceeded to outline the Duffy School neighborhood with a Day-Glo green felt pen and adorned it with a crucifix. His hand crossed Farmington Avenue and found a section… Within its borders, he drew a Star of David. 'You would be more comfortable here,' he said.”

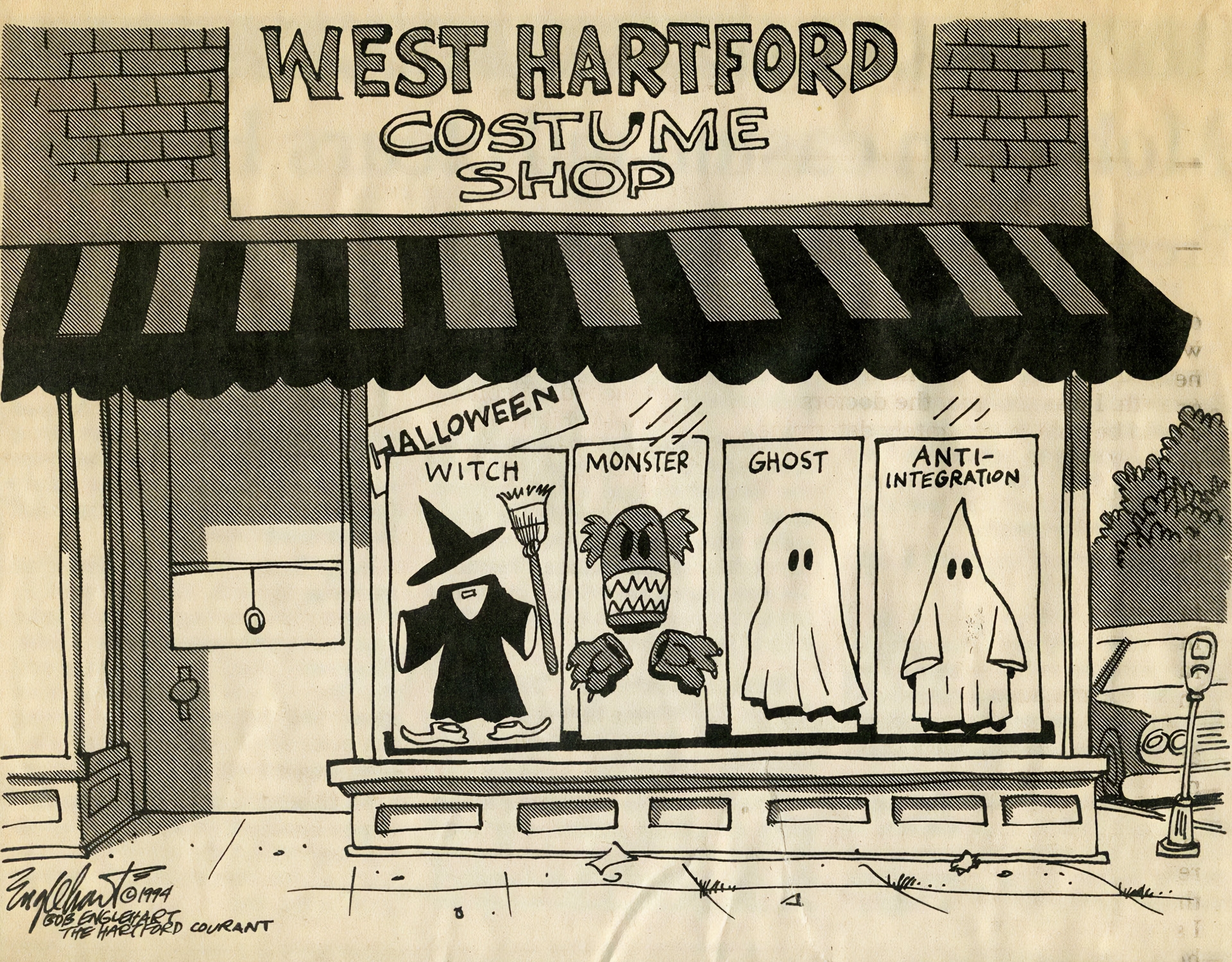

This cartoon from 1994 takes the harmless concept of a costume shop to a sinister level - one of the costumes in the shop is a KKK robe with the title "anti-integration."

Courtesy of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Some members of the Jewish community resisted these restrictive housing practices. Rabbi Stanley Kessler of Beth El Temple called real estate steering “un-American,” confronting real estate agents known to use the practice and even speaking with the ministers of their churches. He stated, “Some Jews wanted to move to [restricted areas] and came to me with these stories that were troubling to me. Two realtors in Greater Hartford, in particular, I had confrontations with.”

We moved to, the sort of the Hartford Golf Club area, which actually had a restrictive covenant and did not allow Jewish people.

West Hartford, Connecticut

ViewHide Transcript

We lived in a two-family house and we bought on Foxcroft Road. And then when our youngest son was in sixth grade, we moved to, the sort of the Hartford Golf Club area, which actually had a restrictive covenant and did not allow Jewish people. And now I think on our street, there are four or five houses that have Jewish owners. And so it's interesting that Jews were not allowed in that area, and there's a strong Jewish presence there now.

Our two-family house was on Dover Road and we actually sold that home to HUD for affordable housing. And then we purchased our house on Foxcroft. And no it was not a Jewish neighborhood and that was something that actually I wanted for my children to not live in a Jewish neighborhood, but have Jewish education and understand their roots and the ethics and the culture. But no, that was not. That was something that we were actually looking to... And the traditional Jewish neighborhoods, many of the houses, a lot of people have wonderfully survived for years. As I said about, you know, our neighbor who was a Holocaust survivor. Many stayed in their homes. So there were a lot of older people in homes and we wanted to be in a younger neighborhood. And so that also made a difference.

West Hartford’s ongoing dialogue about affordable housing and equity has shown that there is work yet to be done. Certain sections remain exclusive: less than 8% of the town’s total rental units are affordable. Zoning regulations continue to favor single-family homes that are unattainable for many. Although West Hartford champions diversity in many ways, displays of racism—both individual and institutional—betray systemic problems that still need to be solved.