Explainers

From unwelcoming attitudes to threats and violence, excluding people from living in a community persisted throughout our nation's history through individual actions and systemic barriers.

![]()

Introduction

0:00

Introduction:

Why do you live where you live?

Do you pay a mortgage?

Or do you pay rent?

Who are your neighbors?

Who aren’t your neighbors?

The places and spaces where we live do not happen by chance and aren't solely the result of individual choices.

Federal, state, and local governments have created and endorsed policies that have segregated our communities. These practices are part of a long history of racism and exclusion in America.

But segregation wasn’t just something written into law…

It was sustained by the actions of real estate agents, developers, mortgage lenders, homeowners, and millions of everyday Americans.

Segregation wasn’t isolated to a few communities…

It was pervasive. You can find it almost everywhere.

Picking up momentum in the 1890s and continuing throughout the twentieth century, city planning, home financing, public housing, and real estate practices created a system of residential segregation.

It was a nationwide system and looked different from place to place.

It was supported by all levels of government.

And it was often enforced through violence and the threat of violence.

White Americans had clear advantages. Homeownership and healthy communities gave many the chance to live out the American dream.

But this dream came at the expense of other groups who were denied those same privileges…denied the chance to build wealth, attend excellent schools, and access quality healthcare.

And the impact has been felt generation after generation.

For people negatively affected by this history, these practices are often well known. For others, it is a history that has been deliberately ignored, minimized, or dismissed.

But if you look closely, there are stories of exclusion and resistance in every community.

This online exhibition will take you inside some of these stories…inside the history of residential segregation in communities from Connecticut to California.

Why does it matter?

It matters because where we live affects our quality of life.

It affects our resources and opportunities we have. It impacts our lives, every day.

![]()

What Divides Us?

0:00

What Divides Us?:

When you hear the word “segregation,” what comes to mind?

You might be thinking of old photographs of “Whites only” water fountains and lunch counters.

But segregation was a more widespread practice than many people realize. It became entrenched in the 1890s because of deliberate government and individual actions.

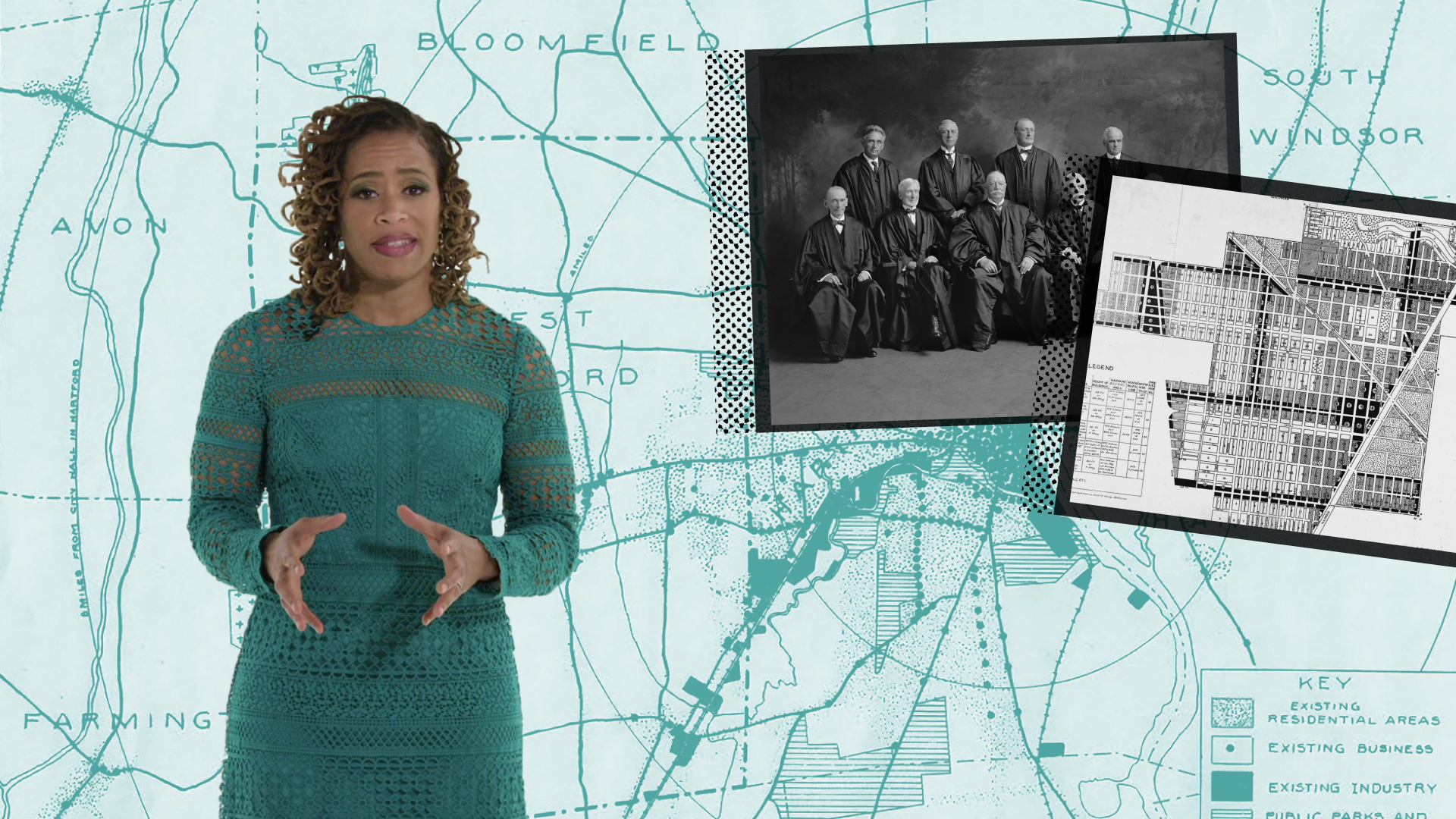

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, and a new era of racial segregation dawned on the United States. When a mixed-race man named Homer Plessy was arrested after refusing to sit in a “colored only” railroad car, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld segregation, establishing the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

This case opened the floodgates, and racial segregation laws spread throughout the South.

Soon, a rigid system of customs and laws known as “Jim Crow” enforced the practice of treating Black people as second-class citizens.

But segregation wasn't just a southern problem.

By 1920, formal systems of segregation affected Americans nationwide, dividing populations along racial, religious, and ethnic lines.

Opportunities for education, wealth building, and housing were reserved for White Americans and denied to people of color, religious minorities, and some immigrants.

And while segregation was a national policy, it was carried out by people and institutions at the local level.

For many Americans, who you were limited where you could live. In places like Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles, Black newcomers from the South were isolated in inner-city ghettos and slums. In the Southwest, Latino residents were segregated into urban barrios. And on the West Coast and in major cities across America, people of Asian descent were hemmed into segregated Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and Little Manilas.

Residential segregation was enforced on the books and in the streets, with restrictive covenants and white violence dividing neighborhoods by race.

As the twentieth century wore on, segregation hardened across the country, becoming a pervasive aspect of American life, and limiting the progress of millions of Americans.

![]()

Migration and Discrimination

0:00

Migration and Discrimination:

The history of the United States is a history of migration—of shifting populations across the American landscape.

Some migrated of their own free will. Others had no choice.

Between 1890 and 1970, migration transformed the nation’s racial and ethnic makeup.

From the start, the U.S. government forcibly removed Native Americans from their ancestral lands, subjecting them to genocide and forced assimilation.

After the Civil War, Black Americans freed from slavery were eager to start afresh, and many moved to southern cities.

But urban neighborhoods became more segregated by race. And city governments worked to keep it that way.

As Black Southerners faced an onslaught of discrimination, violence, and economic oppression, many looked to the North in hope of refuge.

It was the start of the Great Migration. Between 1915 and 1970, around seven million Black Americans moved from the South to the North and the West.

The Great Migration picked up pace during World War I, as northern factories powering the war effort needed laborers.

But the new arrivals faced fierce competition for housing and jobs. Many fled the segregated South, only to be forced into dense neighborhoods popularly known as Black ghettos or slums.

Towns and cities were also reshaped by immigrants who came in search of economic opportunity but faced an uphill battle in being accepted as American.

In the West, Chinese immigrants powered the Gold Rush and the building of the railroad. But in the late-nineteenth century, they confronted rising hostility, and eventually, near-total exclusion.

Legal discrimination of Asian immigrants was backed up by violence and intimidation. Dozens of western towns cast entire Chinese communities out of their homes. And in the early twentieth century, state and local governments passed laws to prevent Asian immigrants from owning land.

Between 1880 and the outbreak of World War I, twenty million immigrants arrived on U.S. shores. Most were Jews, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians from southern and eastern Europe.

They struggled against discriminatory employers and landlords. And they faced violence from their neighbors.

But they forged on and created communities, like the Jewish enclave in New York’s Lower East Side or the Polish community in Cleveland known as Little Warsaw.

Across the country, native-born Whites saw these overlapping migrations as a threat.

Using laws, harassment, and violence, they put up walls around their own communities.

And over time, the White masses would move out of the cities altogether, giving rise to a suburban boom.

![]()

Hate Segregates the Nation

0:00

Hate Segregates the Nation:

White supremacy and violence helped sustain segregation in American neighborhoods.

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan became a major force in upholding white domination and enforcing sundown practices. During this time the KKK was at its most powerful. The Klan drew millions of members not only from the South, but from the North and West. Nearly 45% of Klansmen lived in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio alone.

The new KKK did not just target Black people. Klan leaders hired public relations experts to help broaden their reach. They sold tailored messages to different areas, rallying Klan members and their families against Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and other minorities.

These rebranding efforts were a success. Police officers, judges, and elected officials openly flocked to its ranks, giving the group a veneer of respectability and lawfulness.

Sundown towns were another key example of white supremacist tactics. Beginning in the late-nineteenth century, these all-White communities excluded Black people and other minority groups by custom or through laws and threats of violence.

The name comes from the practice of allowing people of color to work in a community as household staff, day laborers, or as hired hands in factories or agriculture. Despite being allowed to work in the town by day, they were forced to leave by sundown.

Some towns had warning sirens or signs posted at their borders, telling people of color to leave by sundown. Often, the rules were unspoken but widely known. Most sundown towns had no official signs or ordinances on the books, but all knew who was welcome…and who was not.

During the Great Migration and periods of increased immigration, many White communities in the North and West rallied with the KKK to preserve their neighborhoods against the perceived threat of racial minorities.

They organized neighborhood associations, targeting Black newcomers and others they deemed unacceptable with tactics ranging from subtle social pressures to outright mob violence.

Between 1917 and 1921, at least fifty-eight Black-owned properties in Chicago were firebombed.

In 1951, a mob of thousands attacked the home of a single Black family in an all-White Chicago suburb, Cicero. They threw lit torches through windows and smashed their furniture to pieces, causing $20,000 of property damage.

But Black people did not simply accept white supremacist violence and attacks on their homes. They attempted to defend their families and homes, and in rare cases were successful in court.

In 1925, Dr. Ossian and Gladys Sweet realized their dream of homeownership and purchased a home in an all-White neighborhood in Detroit.

When a white mob attacked the building, shots were fired from inside, and a man was killed. Sweet and his friends were charged with murder.

When the case went to trial, the NAACP and well-known lawyer Clarence Darrow defended Dr. Sweet—and won.

For many Black Americans, the Sweet case proved that Black people also had the right to defend their lives and their property.

It was just one example of countless acts of resistance to white supremacy, violence, and hatred.

![]()

Discriminatory Zoning

0:00

Discriminatory Zoning:

Over the last century, residential segregation was enforced through two key tools: public zoning laws and private restrictive covenants.

In 1910, the first zoning ordinance was created in Baltimore after a Black attorney bought a house in a prestigious White neighborhood.

In response, the city passed a law to stop Black people from moving into majority White blocks, and vice versa. Anyone who did faced a hefty fine and a year in jail.

The Baltimore ordinance was too vague to stand up in the courts, but the idea behind it took off. Within a few years, Louisville, Kentucky had its own zoning ordinance. It was an attempt to curb rising Black property ownership in the city.

The NAACP prepared a legal challenge, and in 1917, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In Buchanan v. Warley, the Court struck down racial zoning. They recognized it as a violation of the 14th Amendment and the practice became illegal.

But this didn’t stop cities from passing zoning laws. Zoning was often used for the public good, but it was also used as a tool for discrimination. Within twenty years, more than 1,000 American cities had zoning ordinances on the books.

In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court bolstered zoning with another decision, Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co.

The Court ruled that zoning was a reasonable extension of municipal power. The decision gave legal standing to the zoning laws spreading across America.

The impact would be felt for decades. Zoning was and remains a powerful government tool to keep neighborhoods segregated. But segregation was also enforced privately, through restrictive covenants.

Restrictive covenants are rules imposed on property deeds and contracts. Often, these covenants set property requirements like approved paint colors or tree varieties.

But starting in the 1890s, restrictive covenants began to set rules around who could rent or buy a home.

These restrictive covenants were designed to exclude certain races, religions, and ethnicities—whether Chinese residents on the West Coast, or Black migrants in the urban North, or Jews on the East Coast.

They were born out of a common idea—based in racism—that all-White neighborhoods were better investments and places to live. Keeping areas homogenous, became the ideal for White homeowners.

But like racial zoning, restrictive covenants were challenged in the courts.

In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its Corrigan v. Buckley decision, ruling that restrictive covenants were constitutional because they were private contracts.

But in 1948, the Court struck down the legality of restrictive covenants in the case Shelley v. Kraemer. That did not immediately stop people from using them. It would take another twenty years for the federal government to put in place policies that effectively ended the practice.

Even so, once restrictive covenants were on property deeds, they were difficult to remove. Two decades later, the Federal Housing Authority was still granting mortgages on properties with restrictive covenants.

And today, there are an increasing number of states passing legislation to help homeowners to remove racially, religiously, and ethnically restrictive covenants from deeds.

![]()

Discrimination and the Suburban Boom

0:00

Discrimination and the Suburban Boom:

How did America become a nation of suburbs?

The federal government was the major force making this possible and it accelerated after World War II.

Before the war, most Americans were renters.

The modern foundations for suburban growth were established in 1944 with the passage of the GI Bill. It gave returning servicemen a range of benefits, including education funding, job training, and low-cost home loans.

Millions of White veterans took advantage of this new pathway to homeownership.

But it was a different story for veterans of color. Even though the law did not explicitly exclude them, racial discrimination by the banks prevented most from accessing their benefits.

The federal government also fueled the suburban boom through investment in highways.

The earliest suburbs developed as a way for Americans to escape crowded cities while still being close enough to commute to work via streetcar or railroad.

In 1956, the Federal Highway Act was passed, and America’s interstate highway system was born. The act authorized 41,000 miles of new interstate highways. But for new roads to be laid down, there was a sacrifice. Black and Latino families bore the brunt of it. They saw their neighborhoods demolished or bisected while White neighborhoods were most often spared.

The new highways made it faster and more affordable for suburbanites to commute to cities. But it was mostly White homeowners who enjoyed these benefits.

The exodus of White families moving to the suburbs became known as “White flight.” Approximately two White people left northern cities for every Black person who arrived during the Great Migration.

Even families of color who could afford the suburbs were excluded through discriminatory practices, such as steering and racially restrictive covenants.

Meanwhile, White suburbanites justified their segregated communities by focusing on their rights as homeowners and taxpayers. They felt they had the right to control who their neighbors were without the government interfering.

Together, these forces helped White families realize the American dream of homeownership. But families of color were largely left out. Some formed their own suburban communities while many stayed in the cities.

The effect of these disparities would be felt for generations, widening the wealth gap between Black and White Americans as properties in White suburbs rose in value.

![]()

Shady Real Estate Practices

0:00

Shady Real Estate Practices:

Public policy wasn’t the only thing that excluded Black people from desirable areas. The private real estate industry played a key role in keeping neighborhoods all-White.

In the 1910s, America’s real estate industry established national standards that promoted segregation.

Real estate agents advocated for the false belief that the presence of Black residents drives down neighborhood property values.

Starting in the 1920s, developers, brokers, and agents used a variety of tools to exclude Black families from homeownership.

We’ll start with “Steering."

Steering occurs when an agent tries to guide a homebuyer to or away from a particular neighborhood based on their race or religion. This includes agents steering White families from Black neighborhoods or agents steering Black families away from White neighborhoods.

Though outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, it remains common to this day.

Another practice is "Blockbusting."

This is where agents leverage racial prejudice to manipulate White homeowners into selling their homes at lower prices. Agents might hire a Black actress to walk around the neighborhood with a baby carriage or stage a fight between Black men to convince White homeowners to sell cheaply out of fear of neighborhood change.

Then, the agent turns around and sells the property to a minority homebuyer at a much higher cost.

Next up: “Contract Selling.”

Normally when you purchase a home, you get a mortgage loan. That way, you can buy the home now and pay it off over time.

With contract selling, a homebuyer shells out a large down payment for what’s called a “contract to deed.” The buyer pays off the loan in monthly installments but doesn’t own the home until the loan is paid in full.

In the meantime, the contract seller holds on to the deed and can evict the buyer whenever they want to, often for only minor offenses. A buyer who misses just one payment runs the risk of losing their home.

In the 1950s and ’60s, an estimated 85% of houses sold to Black families in Chicago were “contract to deed.” Contract selling robbed these families of billions of dollars.

This ruthless practice continues to this day, especially in poor and minority communities hurt by the 2008 financial crisis.

![]()

Taking to the Streets

0:00

Taking to the Streets:

Between 1890 and 1950, the segregation and isolation of communities of color deepened.

But there were always those who fought back.

Although most Americans are familiar with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the seeds of that movement were sown a century earlier. In fact, the first Civil Rights Act entitling all Americans to full and equal enjoyment of public accommodations passed in 1875, only to be repealed by the US Supreme Court in 1883.

At the turn of the twentieth century, people began organizing in new and unified ways to attain full civil, economic, and social rights.

Some resistance was born out of the church. Religion had long been a powerful source of unity for Black communities, and Black congregations challenged Jim Crow laws, segregation, and violence.

Between 1890 and 1910, the number of Black professionals doubled, and more and more middle-class Black families moved into White neighborhoods.

Though many were met with fierce resistance, others became pioneers forging strong communities in urban spaces. On the forefront of the battle for Black civil rights was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP.

In 1909, Black leaders including W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell and White activists founded the NAACP to challenge discrimination and violence.

Within a decade, there were more than 90,000 members across 300 branches. The NAACP took the fight against residential segregation to the courts, with cases challenging racial zoning and restrictive covenants.

The era would see the founding of more organizations working to protect the rights of people of color including the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1896, and the National Urban League in 1910. In 1913, The Anti-Defamation League was founded to fight the escalation of anti-Semitism, including violence against Jewish businesses and religious institutions that was inspired by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

As Black people advocated for their rights, white supremacists reacted with violence.

In the summer of 1919, violence broke out across America. In what became known as the Red Summer, White mobs attacked Black communities in dozens of cities and rural towns.

Black people saw their homes and businesses reduced to smoldering ruins and lost millions of hard-earned dollars. More than eighty-three Black men were lynched, in public spectacles designed to spread terror and enforce white supremacy.

Chicago saw one of the worst outbursts of violence. That summer, simmering tensions over housing, jobs, and policing ignited five days of violence—leading to the deaths of twenty-three Black residents and fifteen White residents.

Two years later in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a White mob descended on the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood. They laid waste to thirty-five square blocks, including a business district known as Black Wall Street and killed as many as 300 people.

This wave of violence exploding across the urban North and West made racism impossible to ignore. It was plain for all to see that it wasn’t solely a southern problem.

Black reformers and White allies knew they needed to dismantle segregation.

They continued to challenge racist laws and policies.

But all the while, White residents continued expanding segregation through private tools—ones that would prove much harder to fight in the courts.

![]()

Challenging and Changing the Law

0:00

Challenging and Changing the Law:

Housing was a key battleground for twentieth century civil rights organizers.

Activists won a victory in 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that racial and religious restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. But private covenants continued to be placed and appear on deeds.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Brown v. the Board of Education, declaring segregation and the doctrine of “separate but equal” unconstitutional.

The momentum continued to grow. After years of mass sit-ins, protests, and voter registration campaigns, activists won passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

These were remarkable gains. But there was still much work to be done.

Civil rights activists turned their attention to the urban North—to the struggle for fair housing.

Encouraged by Chicago fair housing advocates, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. moved his family to Chicago’s West Side in 1966 to put a spotlight on housing inequality in one of America’s most segregated cities. It was the start of the Chicago Freedom Movement.

That summer, peaceful protesters marching in an all-White neighborhood were struck with bottles and bricks thrown by white mobs. Dr. King said the racist mobs in Chicago were more “hostile and hate-filled” than anything he had experienced in the South.

On July 10th, 1966—a day known as Freedom Sunday—King spoke to 30,000 people at Soldier Field. He connected impoverished slums with White flight to the suburbs.

The Chicago Freedom Movement helped build support for the passage of a Fair Housing Act. But the legislation stalled. Dr. King’s assassination in 1968 injected a new urgency and political will into the fight.

On April 11th, 1968, the Fair Housing Act was signed into law, prohibiting discrimination in home sales and rentals based on race, color, religion, or national origin. It was amended in 1974 to include sex, and again in 1988 to protect people with disabilities and families with children.

The Fair Housing Act was a major victory for the civil rights movement.

While progress has been made, many of the law’s promises have gone unfulfilled.

More than half a century later, there are still extreme racial disparities in homeownership. Thousands of housing discrimination complaints are filed every year.

The fight to integrate American neighborhoods continues.