Oral Histories

Millions of people experienced housing discrimination due to their race, religion, or ethnicity. Hear stories from everyday people and dedicated fair housing activists.

Views, opinions, and information expressed in the Voices and oral histories are solely those of the interviewee and not the Unvarnished project and its partners.

![]()

Mayor Shari Cantor

West Hartford, Connecticut

0:00

Mayor Shari Cantor:

When my parents were looking to buy a house, it was very clear they wanted to be in a Jewish area. They weren't observant Jews, but they wanted to be in a Jewish area. But there were REALTORS® that were helping them to decide where they should be. I remember my dad telling me about a house that they looked at on Mountain Road that was not a Jewish, you know, kind of a Jewish street or Jewish area. And the REALTOR® said, you don't want to look at that house. And so that was sort of a way to help, to kind of guide people. And I'm sure they had told them they wanted to be in an area with Jewish people. But I don't, you know, that was an interesting comment on his part to share.

Most families had a story of why they came to the United States and maybe why they came to the area either they were from Hartford, West Hartford. When I went to school the schools were closed on Jewish holidays, not only because, both schools I think we're closed. I'm not really sure actually whether Conard, because I had heard that Conard wasn't closed on a Jewish holiday and just Hall. Actually, the North End of town had a bigger Jewish population. And I think that was for again, several reasons there was a critical mass of Jewish people in the North End. And so that's where synagogues were. But also and that's self-serving, right? But also, I do think there was some guiding people to Jewish areas, partly because Jews wanted to be with Jews, but also probably because there were other areas that just maybe weren't as accustomed to having Jews or even welcoming to having Jews. But even in the North End of town, there were areas that did not traditionally have Jews.

![]()

Mayor Shari Cantor

West Hartford, Connecticut

0:00

Mayor Shari Cantor:

We lived in a two-family house and we bought on Foxcroft Road. And then when our youngest son was in sixth grade, we moved to, the sort of the Hartford Golf Club area, which actually had a restrictive covenant and did not allow Jewish people. And now I think on our street, there are four or five houses that have Jewish owners. And so it's interesting that Jews were not allowed in that area, and there's a strong Jewish presence there now.

Our two-family house was on Dover Road and we actually sold that home to HUD for affordable housing. And then we purchased our house on Foxcroft. And no it was not a Jewish neighborhood and that was something that actually I wanted for my children to not live in a Jewish neighborhood, but have Jewish education and understand their roots and the ethics and the culture. But no, that was not. That was something that we were actually looking to... And the traditional Jewish neighborhoods, many of the houses, a lot of people have wonderfully survived for years. As I said about, you know, our neighbor who was a Holocaust survivor. Many stayed in their homes. So there were a lot of older people in homes and we wanted to be in a younger neighborhood. And so that also made a difference.

![]()

Nancy Chen

Community Leader

0:00

Nancy Chen:

When we moved to Naperville, there were only maybe six or seven families. And yeah, in those days and we got together for dinner and then we got together for New Year's parties. And that lasted for several years until Naperville, until the Chinese-American population grew bigger and bigger. And I always remembered that we were the last family to host a New Year dinner at our house. And at that time, I think there were about 15 families. I would say that would have been around 1976 or so or 1975. And then it got so big, people say, “Well, we can't hold that at our house anymore.” Nobody wanted to offer their houses anymore. And then we start looking outside. I can't remember where we held. I don't think it was the high school, because it wasn't that large, but we held it at a public place. And so then surpassing by 1979 or 1978 that we form a called Naperville Chinese Association. And so the association took over the celebration of Chinese New Year and evolved and became bigger and bigger every year.

![]()

Dennis H. Cremin, Ph.D.

Historian

0:00

Dennis H. Cremin, Ph.D.:

So, this incredible transformation is going on. And as you point out, there had been the visit of Martin Luther King in the 1960s. The Supreme Court cases related to the relocation of high-tech jobs, most spectacularly Bell from New Jersey into the Midwest. And so, all of these really, what increasingly were high-tech jobs, cutting edge jobs, this whole corridor here, and so that becomes part of the story. And that's the part that we tend to celebrate the most. Right. What is not being taken into account is that this is an incredibly White community that is also clearly evidencing signs of being a sundown town. What I find interesting is the pressures of growth are going to shift and make this community different. The other thing that really stands out to me is the context. Why is it that Aurora looks the way it looks and Naperville looks the way it looks? OK? Because the demographics of Aurora look so different. And so, when you see that, you can see that clearly, Naperville was a sundown town. Otherwise, it probably looked more like Aurora in terms of its demographics. And it does not.

![]()

Dennis H. Cremin Ph.D.

Historian

0:00

Dennis H. Cremin Ph.D.:

I'm going to tell a personal story. I grew up in Hollywood, California. My grandmother was in domestic service in Beverly Hills. Beverly Hills is a famous sundown town and she was an Irish Catholic who lived in Hollywood. I as a young man, and I probably was about 14, I started going to a Jewish deli out in Glendale, California, and I asked my father, I said, “You know, why do they call it Lily White Glendale?” And my father turned on me, I mean this is one of the kindest people on Earth, and he says “You know why!” and I said “I really don't know why. It seems like a lot to say, Lily White Glendale.” And he says “Well, you know why?” And he wouldn't really answer the question because you don't speak about the ugly race relations in the United States. This is something that you do not talk about. What do you do with this? Because you're told and you know, I'm obedient to my father as much as I could be. You don't speak about this. But this is exactly the issue that we have to talk about.

![]()

Omobolade (Bola) Delano-Oriaran, Ph.D.

Education Equity Advocate

0:00

Omobolade (Bola) Delano-Oriaran, Ph.D. :

As a consultant for under the umbrella of Engage to Impact, I engage educators not to get all focused on a phrase. What is the outcome here? You know, I mean, when I go back to the 60s and we've had what we called multicultural education, we have anti-bias, we have cultural relevant, cultural responsive. I could go on and on and mention all those pedagogies, what is the outcome. So I need us to focus on that outcome, and continue to do what we do best in the classroom. This is also a strategy to distract us from what that outcome is all about. OK. And for me, from the perspective of African heritage, that outcome is liberation. It's freedom. It's social justice for Black families, for Black girls and boys in America. So we can't afford to get distracted by that. And as a member of African heritage, it's a reminder that our work is not done and that we have to continue to agitate and advocate and engage and challenge and ask questions. It's a reminder for supporters of African heritage that this is now the time to intensify efforts to support African heritage.

African heritage is not always going to have its members at that decision-making table. However, if you are a supporter of African heritage, you know what we stand for. Speak for us for full inclusion. African heritage understands we have a variety of strategies that we use in engaging the community to do more. And as we think about those strategies, one that comes to mind, as a scholar that uses the strategy called authentic community engagement, also known as ACE. One of the strategies that we use is ensuring that we continue to have community events not just relegated to February, but every month of the year to show that we are here. We have ownership. And it's important for us to be represented. So for our organization since the 1990s and even before we were officially incorporated, we've been doing a series of community events and those community events have been the events that have actually brought concentrations of Black folks together. To the point you have folks in the communities saying, “Oh, where are they coming from?” And we are saying “right here in the community, they've always been here.” If you do more, you will attract. If you want people to have a sense of belonging, you have to continue to intentionally create initiatives that are centered on Black folks and about Black folks and with Black folks.

So as we think about those initiatives, African Heritage started the first Black History program for the community in February. We started that and now quite a number of communities are doing it. You will find out that all of our events are free. That's intentional. As we continue to engage, attract people to come into our world and see our world living in America as Black folks. From our perspective. So we are always going to have a variety of activities. So on one hand, we have that February Black History program. And if you I didn't say Black History Month, I said February Black History Program because in March, in April, in June, we have a June Black History program, in January we have a January Black history program. So folks, it's every day, every year, okay, every month. So we do that Black History program, we host what we call Juneteenth. And for us, Juneteenth, if you go back and look at the Emancipation Proclamation on one, folks, folks will say Black folks are free, but we have not achieved freedom yet. Okay, so even when you go from 1863 or when you go to 1865, we still have not achieved freedom yet.

So Juneteenth? Yes, we have forced educators out there. When you have a unit, and you have a unit on freedom, and your doing a unit for July 4th, do us a favor. You got to include Juneteenth into that unit. And from my perspective, with multiculturalism, you got to look at what freedom means for a variety of groups. That's when you know that you have fully infused, culturally relevant pedagogies. As you do these pedagogies, you still got to center it on racism in America. You have to. So when we talk about critical race theory, it continues. It's infused in everything you do, even in celebrations, even in community activities. So as an organization, we continue to agitate, so we do Juneteenth. In addition to that, we know that education is important, formal education is important. We know that in ensuring that our people, Black folks are free, they need to be financially independent. So for African heritage, it's important that we position Black folks in this area to be financially independent. How do we do that?

One example, we studied what we call the African Heritage Emerging Student Leaders Institute. That happens in February, and we bring it's a collaboration between African heritage, a few corporations and about seven or eight school districts. We bring over 700 to a thousand high school Black high school students together in one setting. It's always very sad when a Black high school kids look around. Said on one hand, because they say. It's kind of like a double edged sword here, on one hand, is sad because they're looking around and they're saying, where did all those folks come from? But on the other hand, with joy, they're looking around and saying they look just like me. But when we have this leadership institute, what we always are intentional in doing is bringing Black adults to Batson. And our students, I'm looking at kids are looking to see. Are you in this community and we are saying yes and our students are looking at that, oh my gosh. I don't feel isolated anymore. But it's also a message to the school district that they don't. Our kids don't see themselves in the curriculum. And there is a need to do that. And there's a need to continue to seek Black folks in the community and integrate them into the curriculum.

So that's important, but as we think about the leadership institute, what African heritage also does is. Provide professional development for educators in the area on how to authentically engage with Black children in the area. OK, so that's African Heritage Emerging Student Leaders Institute. I will also say that when we started the institute, it was just four Black high school students. We have now included college students and college students that come from a variety of institutions. I mean, you have a range of colleges and universities, but we do that because African heritage sees it as a strategy to recruit. If Black students feel a sense of ownership and belonging in the area when they graduate, they will come back and work in the area. Being Black in America is traumatic. It is a trauma. It's traumatic. It was traumatic for generations ahead of me before me, and it's still traumatic. And I continue to be fearful for not just my daughter, but the many daughters, granddaughters, grandsons, sons out there in terms of generations to come.

One of the community engaged initiatives that African Heritage was an architect of with many partners, but including data care chat was to host a it became a state event as a result of our relay. As a result of our contributions was what is it like to be Black in this community? And you know. That is a. question that I also know is traumatic for any Black, for any Black person. That question is because it brings up generations, years, centuries of inequalities here. But African Heritage hosted, not only hosted, but planned Black in America, and we brought stakeholders together. To engage from a critical point of view. And what it means to be Black in the Fox Cities. And there were quite a number the stakeholders had they had the access they had the power they had the resources to create change, institutional change. So we brought communities together. When we did that, we when we hosted that event, African Heritage actually chartered buses to bring groups as far as Milwaukee to the area for us to talk about to address what it means to be black in America. In addition to that, we also. We had quite a number of college students who also came to that event being Black in America, and it was more than a one day event and for our organization, we continue to do Black in America. So that's every day for us.

But for the community. I remember when we hosted that event and we had that event and one of… there were quite a number of goals that were identified that the community needed to address. But the community was also intentional with a partnership of the care chat. They were intentional on ensuring that there were clear outcomes. To propel us into action and the outcomes was supposed to guide. So one of the outcomes that came out of the focus on Black in the area dealt with the day-to-day racial aggressions that Black folks were experiencing in our communities here. OK. Some folks talk about all these areas may not be sundown communities anymore. However, it's all about interpretation. OK. We know as Black folks that we continue to experience racial aggressions that sends messages that we shouldn’t be hanging out in any of our communities because we don't wish, we don't want to be seen. It's not that we don't want to be seen, but they don't want us to be. They don't want us to be in the area.

So as we talk about outcomes of being Black in America. So one that was very clear is our people continue to experience racism every day. How going to school Black, you are excluded in a variety of ways, shopping while black, you're followed an oh my gosh. How do you drive a car, a nice car, and police officers believe that you don't have enough money. Or you shouldn't even be driving that car. Driving while Black and being profiled. So what was very clear to those stakeholders is as you look at all areas in our communities. Walking while Black, driving while Black shopping while Black residing in while Black, you can't even walk into the streets of the communities. Yes, I said it. You have all those Karens calling police officers wondering what you are doing in the neighborhood, not realizing that you are an engineer and you work for one of the paper companies in the area. And in fact, you're a scientist and you are an innovative scientist and you hold so many patents that have contributed to the vitality of America. But then Karen called the police officers on you because they believe you probably couldn't afford to be in the neighborhood. So that was apparent to quite a number of our stakeholders that attended the event on Black in this area. It was apparent that racism continues to happen on a day-to-day basis, so that was very apparent but was also apparent is Black folks continue to face racism in the housing patterns of this area. On one hand, having access again, this is where I believe that when you begin to look at the intersectionalities of the identities that Black folks have. It results in a layer of discriminatory lived experiences.

![]()

Sarah E. Doherty, Ph.D.

Historian

0:00

Sarah E. Doherty, Ph.D.:

You have William Joseph Simmons reviving it in 1915. He never really gains that much momentum, not very effective at thinking of it as a broader sense, borrows the name borrows the alias invisible empire that came with the original Reconstruction-era Klan. But there really is nothing invisible about this 1920s Klan. They are very clear and kind of flaunting who is their membership.

They're not hiding in the fringes. They're not, you know, operating mainly at night, terrorizing freedmen at night. They are very much front and center. They are publicly advertising in newspapers for 100% Americans. They are holding these large public gatherings, bazaars, inviting the whole family kind of membership, recruitment drives, rallies. In 1925, they had this major march with 30,000 members through the streets of Washington, D.C.

So yes, it's very much a Klan operating in front and center in the daylight, and it's attracting mainstream Protestants. So these aren't kind of fringe elements of society. They're attracting your everyday White Protestant Americans to their ranks. You have different levels of Klan activity in different parts of the country. We think about this 1920s Klan. As we said, it's very much expanded beyond the former Confederate states. Almost 45 percent of the membership of the 1920s Klan comes from the states of Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois. But a lot of this 1920s Klan is urban-based as well. It's not something that's happening in small rural communities. It is very much present in urban and suburban America.

![]()

Mary Donohue, MA

Historian

0:00

Mary Donohue, MA:

Mary Donohue: West Hartford had, as I said, this huge flurry of real estate agents and developers. In 1922, they had three hundred building permits pulled. In 1922, they decide that they really want to instill some kind of order and I have to say exclusivity onto the development of West Hartford's Real Estate Market. So they start to appoint a committee that puts together a zoning committee. They study other models from the country. They get one of the leading zoning proponents to come in and write a report for West Hartford. So West Hartford, by 1924, has their area divided upon the zoning map into zones, which is not uncommon, that's what Euclidean zoning does. So there's commercial areas, there's residential areas, and there's industrial areas. And the idea is to separate those for the public good, have a buffer zone between residential and industrial, for example.

But in West Hartford, they take it a step further and they divide the residential into five different zones, and each zone has a minimum land requirement. It doesn't have a condition that says a house or building has to be of a certain dollar amount. Instead, it says it has to be on a big enough piece of land. So the areas on the east side that develop from 1900 to 1924, and I want to say more hodge-podgy, are diverse, are those areas that were developed before the zoning law came in. That sent more exclusive housing development to the northeast corner, so you have the Golf Club District develop and the Hartford Golf Club moves up and over Albany Avenue. And each time it does that, it opens up land for expensive development, and it also creates the desire for expensive development to be close to the golf club. It also makes Elmwood our industrial area and clearly defines that, so you don't quite have the bungalows next to the factories in exactly the same way you did before that.

So that change in zoning has a huge effect on West Hartford that you can see. West Hartford was also included in the federal government's maps, which are part of what is now called Redlining. And Dr. Dougherty has studied that too and published on that. So the redlining took the federal government's inspectors and looked to see what was happening on the ground for housing. The housing would be downgraded color-wise if it was multifamily housing, or if it had a lot of African-Americans, or it had Foreign-born workers. So West Hartford's principal corridors and Elmwood and Park Road and Boulevard that contain those types of residents and those types of housing structures like triple-deckers, those were all part of the lower designated area in the federal government's maps, and that was supposed to also give bankers an idea of what was a secure area or a not secure area to issue mortgages in.

An interesting thing about West Hartford is that most communities have this “go, go, go all the way through” what are called the “Roaring 20s,” and then we have the depression. The Great Depression hits in 1929. In West Hartford, it didn't make as much of a difference as it did elsewhere because the insurance companies and downtown workers really didn't lay off in the same way that an industrial community did, in places like New Britain who are, you know, heavily factory based. Those communities, yes, sales went up and down, the depression hit, and those workers were laid off. In West Hartford, it's much more of a white-collar workforce. And so they're still building houses all the way through the depression, which I thought was interesting, too. So, I think it's sort of the background to your question about how did West Hartford sort itself out into Catholic areas, Jewish areas, Protestant areas and became at one point pretty exclusively White? It's a factor of what kind of housing opportunities are available. So those multifamily housing types, like triple-deckers or two-family houses could only be built in certain areas of town. And so a lot of those were advertised as an opportunity for a working-class family to buy a two-family or a three-family, live in one section, and rent the other section out.

So that was a way that you could pay your mortgage and be more of a lower middle class or working-class individual and still own a home. Those opportunities are concentrated along those eastern corridors, like I said, on Boulevard, the Protestant very upper-middle-class or wealthy individuals built homes near the country club that made, you know, that made sense. You'd be near the golf club and Elizabeth Park, an area that was already pretty posh to start with, Prospect Hill. The idea of prejudice against foreign-born people of any kind: Italian, Greek, Mediterranean, Jewish, Russian, Poles. All of that comes to a big head in 1924, when the U.S. government severely limits immigration because of this nativism and anti-foreigner kind of public opinion. And so, Dr. Dougherty, you know, his work clearly states that you can't point to one thing that says that was solely anti-Semitism or solely this idea that we want to have a very exclusive community. But that probably both of those factors were at work. But I don't think you can underestimate anti-Semitism.

Interviewer: How do you feel like the zoning plan kind of dictated the future of development?

Mary Donohue: Well, it's the idea that there are five different residential districts and each one requires a certain amount of property. That means that you have to have a certain amount of property for every family that's living there. So the idea that you're going to have a double family or a triple-decker or a small apartment house on a small parcel of land, which was possible in Hartford, is not going to be possible in West Hartford. And so in certain zones, in those zones that require a lot of property. So it really concentrated multifamily housing in certain areas. And I think by the time you get to the 1940s, 50s and 60s, it's certainly evident in how big the lots are, north of Albany Avenue in those residential areas.

Interviewer: What are some exclusionary practices that maybe weren't on the books, but were happening?

Mary Donohue: Yeah, well in the work that the Jewish Historical Society is doing on this and the meetings and programs we've done on that; people were released. It was called steering, but it was this idea that the REALTOR® is going to suggest to you areas that you're going to be “comfortable” in. You still had the Protestant Golf Club, the Catholic Golf Club, and the Jewish Golf Club. And you have to be put up for membership in those. And clearly you wouldn't be accepted as a member if you were applying to one that wasn't related to your faith. Jews and Catholics had done the same thing in Hartford with the hospital, so you had Hartford Hospital, which was a Protestant hospital, and St. Francis, which was the Catholic Hospital, and Mount Sinai, which was the Jewish hospital. Law firms, the same way. The Jewish Historical Society has documented the development of Jewish law firms, there were also Catholic law firms, Protestant law firms, and so there was a lot of, in some ways, invisible self-determination going on. If you were in a certain religious group, you knew where you were welcome, where you could get privileges as a doctor, where you could work as an attorney. So, after the Second War, I think that was still pretty much in place until the 1960s.

My kids, who are millennials, can't understand that because they've gone to birthday parties and bar mitzvahs all over town. And the concept that you wouldn't be welcome because of your family's religion at one of those golf clubs just totally escapes them. But it was still, when I moved here in the 80s, it was still a pretty rigid system. So I think that contributes to that sort of sorting out in housing developments, too. We have developments all the way through the 1950s that, in their deed restrictions, will say things, not just the idea of barring a race, which is one thing; we have those too. Those were kind of invalidated in 1948, but we have a lot of building restrictions in West Hartford that say things like a house has to cost a certain amount of money, has to be designed by a certain set of architects or builders, has to be the other kinds of things. We have some on private roads, for example, that kind of a restriction, and all of those were meant to contribute to that sense of exclusivity, and that if you bought a property there, the property value would always stay high because it came with these restrictions. So I think that, in a nutshell, West Hartford is both typical of any kind of inner suburb development across America, but then it has its own quirky characteristics, like the fact that we were the first town to put zoning in Connecticut. And you can kind of see the ripple effect from that.

Interviewer: But it seems to me that when the developer bought the land, that as long as they were following maybe the lot size requirements for the zoning that they really had a lot of power in terms of being able to dictate things like architects and lot or value of houses, and then also putting in something like a restrictive covenant. Is that true? Do you think that they… How much power do you think they had?

Mary Donohue: Yeah. I think that's true across the country too. On one hand, you can say they have a lot of power over that. And on the other hand, they still have to follow the dictates of the market. So what is your market and who are you marketing to?

![]()

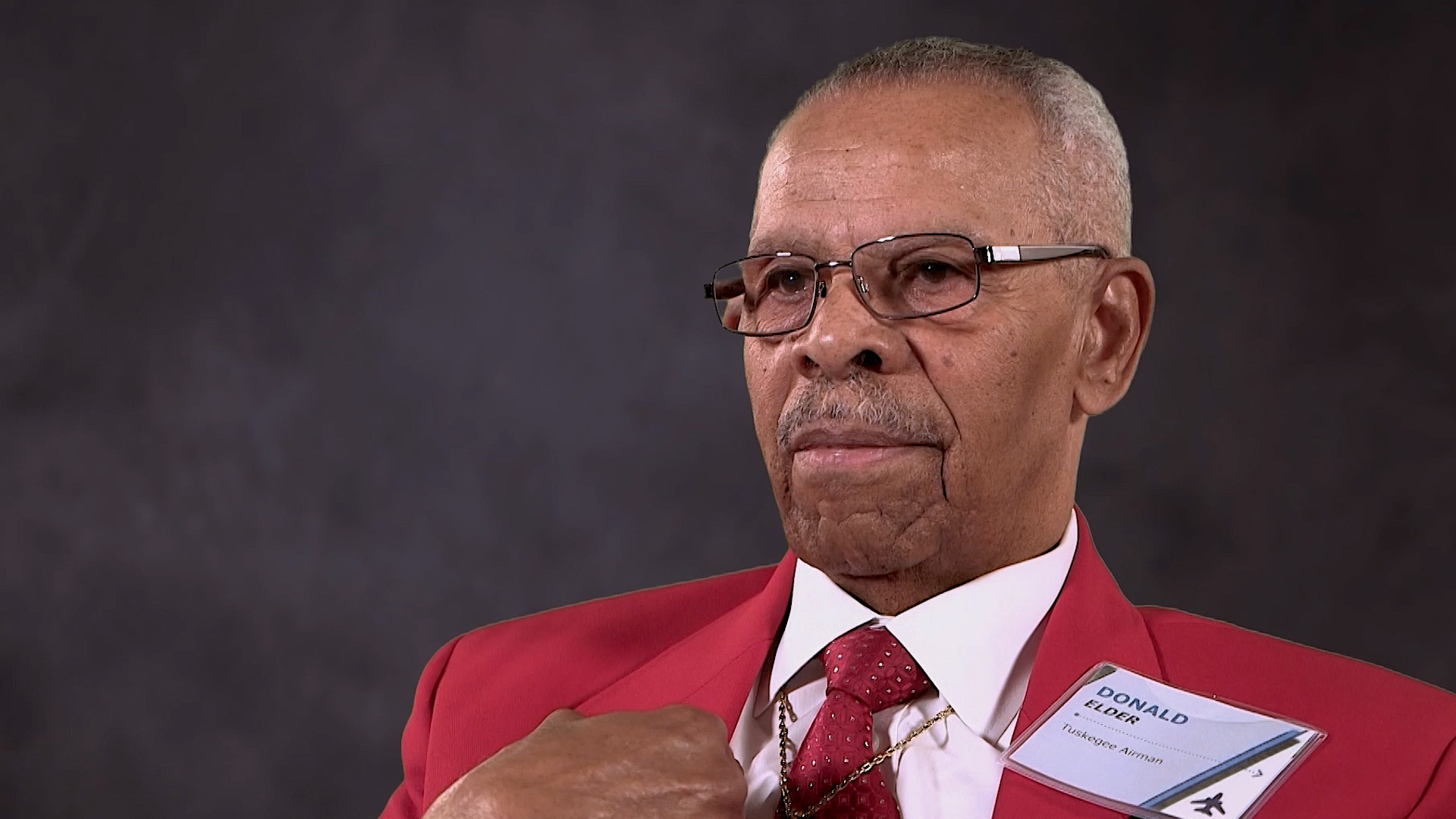

Donald Elder

Tuskegee Airman

0:00

Donald Elder:

While I was there, Grumman decided to send a person, no, it was Northrop, well Northrop Grumman, to send a person to Albuquerque on an airplane they had out there, and the long and short of it is he ended up leasing my house from me because I went back to Columbus.

Well, matter of fact, North American sent Tom Johnson out there to join me after a while. You see, those times again I can always remember, like driving from Columbus. I stayed at the Holiday Inn in St. Louis, Missouri. But when I left St. Louis driving further, they had made a reservation for me in Oklahoma City. When I got to Oklahoma City and I went to the counter at the Holiday Inn. The guy looked at me really startled, and I told him I had a reservation. And I remember him saying, “I don't care what you have. You can't stay here.” Oh, okay. I couldn't stay. So I stayed some little fly-by-night somewhere, and I left Oklahoma City. When I got to Albuquerque, that's when Wizner met me and he made certain that I got into a nice hotel, motel on Central Avenue in Albuquerque. I had that kind of an experience, but that was in 1950, 1960.

![]()

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.

Historian

0:00

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.:

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.: There are a lot of different pieces to how different types of housing segregation came together and ultimately became part of national housing policy. But a lot of these had their origins in private real estate practice beginning in the 19th century and then really accelerating at the turn of the 20th century. So restrictive covenants, especially racially restrictive covenants, were tools that developers had been using since the 19th century to impose legally binding rules on property that anyone owning or potentially living in the property had to abide by. These actually functioned initially on a case-by-case basis to set rules that seemingly were just about the look and feel of a development. However, one of the first legal cases that showed that this was being used to regulate who could live where was against Chinese people in California, but it wasn't against a suburb, It wasn't about a suburb. It was about one single piece of property.

And so what you see in the early 20th century is different strands of segregation. Restrictive covenants, different techniques for planning and laying out streets, the rise of zoning, are all being retooled. They're coming together and they're being put into the service of racist segregation and real estate practice. The reason why, or one of the reasons why this happened at that time was because there was a new wave of suburban developers who were thinking about more long-term returns on their profit. And that was a big difference from a lot of building that you saw earlier in time where people just wanted a very quick turnaround, built a few lots, and got out. This longer time scale where they were looking for profit and they wanted to plan and control developments more. And they took their understandings of race and racial hierarchy, usually as White men, because they were the ones who often had the most access to money and capital, for development.

They took this and they said, What can we do? What tools are available to us to really make these developments racially exclusive and also class-exclusive? Because that, they thought, would be the most profitable thing to do. And it turned out that for many decades they were right. But you get a bit of a chicken and egg scenario. They were right because they also ended up gaining a lot of the power to really develop a platform saying these are the best real estate practices. And because they ended up doing these things locally, but then setting the terms nationally, when it came time in the 1930s, in the 1940s, for federal policymakers to be interested in how to write national policies, they looked to the people they thought were the experts in real estate, and it was these same developers and the same organizations that supported these developers and segregated real estate practices. So you have this trajectory where by the time you get the federal housing policy, you have actually codification of longstanding discriminatory practices that is given new weight and power behind it because now federal rules and resources are going to back up these very practices.

Interviewer: So often people think that this is purely a Black and White story, and you've already mentioned Chinese exclusion in California. We know that there was Jewish exclusion, there was Catholic exclusion, there was Irish.

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.: I think you're absolutely right in that when thinking about the history of segregation, it is not as simple as Black and White. And that's because race is a changing category. Race is not just about the color of one's skin, but actually, race historically is about the relationships between different groups and the relationships to power. So historically, what has happened, what that means, is that generally native-born people of northern European descent had the easiest time claiming to be White. And with those claims to Whiteness, also meant that they had the most access to elected office, the most access to generational wealth in the United States. All these different resources that allowed them to be more likely to be able to set the terms of how things are run.

Now, that's not the case for every individual White person, of course. But when thinking about power in general in these types of categories didn't matter for who potentially was able to get a voice heard more than others. Now what this also meant was that there was a whole hierarchy of Whiteness because prior to the 1950s or so, Whiteness was a very unstable category. And so it shifted a lot, and that meant that there was a lot of debate and a lot of change over time about who actually got to claim Whiteness. This is where a lot of southern and eastern European immigrants who immigrated to the United States, especially in the late 19th century, often saw it in their favor to try and also claim that Whiteness. So, for instance, Jews and Italians who were often the subjects of discrimination and who were sometimes not considered White, found over time that it was to their advantage to try and become as, I guess, equally White as people who were of northwestern European descent. And one of the ways they did that was by discriminating against people who couldn't claim Whiteness.

And this is where you have a hierarchy developing where, and there is a lot more to this, including scientific racism, which is a whole other strand of thought. But this is where you also get into a long differential treatment that includes anti-Blackness really animating every single slot of this hierarchy. And usually, African-Americans were considered to be by law, by in a lot of different scenarios, were often considered to be at the bottom of a racial hierarchy. And so what this meant for housing segregation is that there was a lot of local variation about how segregation played out based on religion and national origin. But usually, one common thread was anti-Black racism nationally that led to housing segregation against African-Americans that informed the potential for everyone else to perhaps actually get a foot in the door. So while that is still an oversimplification, I think thinking about racial discrimination in terms of hierarchy, in terms of a whole sort of list of people with anti-Blackness being a really important factor is a way that we get more complication and nuance than just thinking about Black and White segregation where there was no middle.

Interviewer: The other question that I asked was digging a little bit deeper into the commonly held idea that exclusionary real estate practices really did come out of that World War Two era, that push toward housing veterans. And there's there's not a lot of understanding and you've already talked a bit about it. There's not a lot of understanding that this really formulated earlier. And we get a lot of push about, well, it was really federal housing policy that was driving this, you know, the people on the local level, we're just doing as they were being advised from national policymakers. Can you dig a little bit more into that? And if you want to use a particular example, that's great and if not just on a more umbrella level.

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.: Yes, housing segregation was multi-directional. And when I did my research into housing segregation, I actually begin with the local level because that's where I see the experimentation taking place that ultimately informed national practices and then national policy. So one example would be racially restrictive covenants, and I mentioned that essentially allow set the terms and I keep using that expression, “set the terms.” But I think that's a really important process, setting the terms of what came next. Racially restrictive covenants were community by community-based. I identify some in Baltimore, and then I asked myself, Well, then how did it spread? How did things go from local to national? And sometimes it really was as simple as developers talk to each other. City planners, city government officials talk to one another. Professors started building curricula based on local copies of restrictive covenants and then teaching whole generations of people who went out and worked locally to segregate in certain ways.

So I think that starting with this kind of network of locally-based practices that then started to cohere into a more nationally recognizable form is actually the key piece of the story and the fact that it happened with the rise of Jim Crow. I think it also serves as a reminder that housing segregation was a huge part of how Jim Crow worked in the early decades of the 20th century. And so to ignore Jim Crow housing segregation, to ignore zoning laws that were always local laws that bolstered suburban development and suburban housing segregation, to ignore that is to really erase the entire origins of where federal policymakers got those ideas from. However, there is something that changes with the codification of national policy, and I do think that this is actually a really important piece to how housing segregation is multidirectional. One of the first national housing policies came during the new deal in the 1930s, and that's redlining. However, and I can explain a little bit of what redlining is, which was the federal government created an agency, the Home Owners Loan Corporation, that was going to, for the first time, directly get into the mortgage market. And for people who may have been on the verge of losing their home in the Great Depression, the homeowner and loan corporation was going to potentially take their mortgage, put it on to better, easier terms to meet, and then was going to service that themselves.

That's a massive change, but they had to develop criteria for which mortgages they were going to bail out, select. And that is when REALTORS® were tapped on the shoulder, and only some REALTORS®, usually suburban developers and White brokers and people who worked in those circles. And they helped the federal government write the rules for city by city Redlining maps. So the Baltimore map was made with Baltimore REALTORS®. The Chicago map was made with Chicago REALTORS®, and they worked together to establish the rules for which they were going to make whole areas of the city redlined, meaning there was not going to be much investment there or green, which is going to be the areas that were considered the best bets for the federal government to service mortgages.

And those are based on earlier practices. Green areas were often already segregated. They were segregated suburbs with single-family homes. Redlined areas were often areas where people were African-American. Sometimes the very fact that it was mixed race or mixed religion was enough to get it redlined because there was also a longstanding idea coming out of universities, especially economists, that once an area became mixed race, its property value was just going to decline and decline and decline. All this is to say, these did not start at the federal level, but when it became federal policy in the 1930s and 40s, there was then an amount of resources behind it that became something no one could ignore. And I think one of the biggest examples of this was what's perhaps cited as one of the key moments of postwar suburbanization, which is that G.I. Bill, where returning veterans from World War II were able to get these really preferential loans from the federal government and they could buy houses, often for the first time.

That was discriminatory because. That agency, the Veterans Administration, adopted rules from another agency which had adopted rules from the Homeowner's Loan Corporation, which had adopted practices from REALTORS® who had experimented previously on the ground, beginning in the 1890s. So while there is an important difference between federal resources and power and reach, and local practices, you can't separate the two in this history because you actually need both of them to fully understand the forms that housing segregation took, the timing of that housing segregation, and why it was so widespread in the north, south, east and west.

Interviewer: Thank you. So that springs another question, which is REALTORS®, and specifically the best practices in real estate that permeated the real estate system. Can you talk about how the National Real Estate Board and how their materials that, as you said, were just spread across the country? Can you talk about the influence that it had on these practices?

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.: So beginning in 1908, an organization called the National Association of Real Estate Boards was formed in Chicago, and its aim was to become the main national professional association for anyone involved in the real estate industry. Now from the get-go, this was a segregated organization who based membership on admission to local boards. The Chicago board, the New York board, and those boards had long been segregated themselves, meaning only White men, in general, had been able to gain admission to local boards, meaning that only White men were able to gain admission in the early years to the National Association. The National Association of Real Estate Boards met, and their main goal at first was to make real estate what they called respectable. Because REALTORS® had a reputation they felt for being scam artists and being untrustworthy, and they thought that was going to hurt their profits long term, and it was going to really give the opportunity to real scam artists who, not them, but real scam artists to really, really kind of continue business in a widespread, unchecked way.

So when they got together, one of their priorities was to establish a code of ethics for practicing real estate and for establishing this best practices. And then what they did was established licensing laws, meaning that to actually practice real estate, you had to pass a type of exam in which you demonstrated knowledge and commitment to these best practices and these ethics. What were these best practices? What was this code of ethics? This was based on the idea that REALTORS® should do no harm to a community because scam artists harm the community, but REALTORS® in the National Association of Real Estate Boards only had the best in mind for everyone, so they said. So the code of Ethics built, beginning in the 1920s, so they revised it. So this is another instance where it wasn't there at the very beginning, but it was put there fairly early on. They revised their code of Ethics to say that it was unethical for a REALTOR® to introduce into a neighborhood someone whose race didn't match up with that neighborhood. What they were really referring to was that it would be unethical to show people of color houses in White neighborhoods. And again, Whiteness was defined a little differently back then.

The reason why they thought this would be unethical is by the 1920s, there was this really, really strong consensus within the National Association of Real Estate Boards that race was tied to property value and that Whiteness created a kind of baseline property value and that everything else lowered property value. So everyone else lowered property value. And so it would be unethical to integrate a neighborhood because that would inevitably lower property value, which would be a form of doing harm. This type of practice meant that any efforts to combat segregation within the National Association of Real Estate Boards could be grounds for expulsion from the organization and for the loss of a real estate license. Now, I don't actually have a lot of evidence that a lot of people were fighting against this Code of Ethics within the National Association of Real Estate Boards.

This was something that was voted on, and it didn't seem from the record I've seen, particularly controversial. So what happened was then that this code of Ethics governed real estate practices in the 1910s, 1920s, and again into that federal policy period into the 1930s and 40s. And it was only changed after a major Supreme Court decision in 1948. Shelley v. Kraemer, in which racially restrictive covenants were ruled by the Supreme Court to be unenforceable, not illegal, but unenforceable. So they saw which way that the winds were kind of shifting and that maybe housing segregation wasn't going to be something to publicly stand behind for the decades to come. But in practice, they actually continued it, and one of the legacies of the National Association of REALTORS®, even with all different changes in policy, all different changes in law is that to this day, there is ample evidence that shows that race is still linked to the property value of house and of neighborhoods, and actually has all sorts of differential impacts for how different parts of cities and towns actually get public resources.

There was always, always, knowledge of what was happening, there was always resistance to what was happening and there was always organizations and organizing and activism to try and counter the impact and processes of segregation. So I think that this is where it's really important to acknowledge and shine a light on people who may not have become household names, although some did, who fought tooth and nail to essentially make racial segregation illegal to help people who were working within segregated systems to still thrive. And I'm thinking of a few examples. I write about someone who was one of the founding members of the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which was one of the major civil rights organizations of much of the 20th century. Not the only one by any means. And he helped pioneer what they called a legal strategy, which was one of many different strategies that were being taken at the time.

The legal strategy was to essentially create test cases that would challenge discriminatory laws. And then it was their hope that they would get favorable court rulings that would knock down and eliminate laws. And this would be at the local or the national level. So one example of this was that there was a type of zoning, or essentially municipal land use policy in the early 20th century, that was also about racial segregation. And it was this, the city of Baltimore, beginning in 1910, created a law that Black people could only live on certain blocks of Baltimore. White people could only live on other blocks of Baltimore. But the intent of the law was to actually just stop and regulate the movement of African-Americans from moving into White neighborhoods. It didn't actually equally work both ways. And so the legal strategy that sprung up around this, led by someone named W. Ashbie Hawkins, was to go to court, knock down the segregation ordinance. But the ordinance was repassed, so knocked it down again. And ultimately, though, these ordinances form part of a Supreme Court case called Buchanan V. Warley, where the Supreme Court said that racial zoning is unconstitutional.

So this was just one example of a legal strategy. Sometimes it was met with very mixed success. There were a lot of cases about racially restrictive covenants where the court ruled on the side of the people with the racially restrictive covenant, so there were limits to that. That is one really important strand, though, of how people fought back against segregation. Another way that people fought back against segregation was also by picketing and protest and appealing to history, which I found really fascinating, and I think it's really important. People knew their history and used that to try and craft appeals to knock down segregation. So for instance, again, in Maryland, you would have civil rights organizations that would point to how Maryland was a slave state during the Civil War, but it was part of the union. That meant that there was going to be a specific racial history, that meant that it was particularly egregious when new segregation laws popped up because Maryland needed to remember the sort of wrongs and injustices of slavery.

So these were sort of appeals that were used also sometimes effective, also sometimes ineffective. But one thing that was really difficult with fighting back against racial segregation in housing was that increasingly over time, segregation was codified into more and more structures. So, for instance, there was a property value piece, there’s how schooling worked. There's, let's see what else, there's all sorts of interactions when people tried to bank. That essentially, every system that one encountered in their daily life had as a piece of it somewhere that housing segregation was ok. And if you kind of think about that, it turned fighting housing segregation, sometimes into a game of whack a mole, where if you knock down one law or one community, backtracked on their discriminatory practices, you're going to find potentially that more popped up or more identifiable. And this made it really difficult to combat segregation in a really large way, however, I think there was always, always, always consistently over time, a really strong and robust fight against housing segregation.

I would define the sundown town as a place, a town, a village, a community that prohibited African-Americans from living there or even being there after the sun went down. Meaning that it was a town that was racially discriminatory. And here's what I think is one of the most important aspects of a definition of a sundown town, which is that there is a looming threat of violence. I think that the way that a sundown town enforced its segregation was through the threat of violence against anyone who violated the understanding that that was a town for White people and it was a town where especially African-Americans could not be after a certain time of day. So that threat of violence is, I think, the organizing factor of a sundown town, regardless of where that town may have been or any of the sort of specifics about how mobility and Black movement were controlled.

Interviewer: And in this moment, why is it so hard to track the history of sundown towns?

Paige Glotzer, Ph.D.: I think there are a few reasons. One is that I think that that history may have been available until it was something that would reflect poorly on the town. Meaning that if you have a sundown town, maybe the records existed of that town's activities in the 1950s or 60s. But by the 1980s or 90s, the town didn't want those records to be easily available anymore. So I think that, you know, today it's harder than ever to find records of sundown towns because as time goes by, there's a longer and longer time period in which I think people were willing to acknowledge that it didn't look good in popular perception for a town to have those practices.

So I think that's one thing the time we're in now makes it hard harder than it used to be. Too, I think sundown towns operated a lot of sometimes unspoken consensuses of White residents, especially again to enact violence. And I think that makes us think about what would the records of a sundown town be and let alone would they survive? So these could be conversations at a meeting. This could be some KKK gathering, right? Like these would not necessarily be records written down and put into a ledger book that would be preserved in the city hall, even something that might have been official like particular provisions in deeds, even though there should have been public-facing, sometimes that might have been, there was such a consensus around how this operated. People could have been lax in recording it, or people could have potentially done it improperly or ripped it out. Finally, too, I think that there are records of sundown towns if we expand our definition of what counts as a historical record. So I do think that one reason why people might think that is hard to recover the records of sundown towns is because potentially say, folks have discounted oral histories, have discounted talking to people who have generational memories, and have shared stories that may have happened, right?

So whether I think that there is a certain validity question that has been in play about what sources count as records of a sundown town. And I think that if we expand that notion and we really kind of talk to people, if we expand who gets represented as being able to speak with authority to the history of a community or to the violence of a community, I think then that doesn't solve the problem of difficulty finding records. But I think it actually does suddenly bring into view a lot more potential sources of documentation and substantiation than people, potentially we're working with in the past.

One source that I know people tend to look for are passbooks or any type of documentation where essentially in some sundown towns African-Americans had to actually carry a piece of paper around that would be either marked or carried permission that they were allowed to be there on White people's terms. Those are often held in private collections, though if they survived. But that's usually one way. You can also kind of see evidence that people's movements were being controlled into and monitored into and out of sundown towns. But of course, that depends on just being able to know people who may know people who have something in a box in their attic, so it's very difficult to locate them. I do think also the Black press is sometimes a good source that I imagine is used more today than it used to be by kind of large projects documenting sundown towns. But sometimes I just think like, Where would I kind of see this knowledge being actually publicly recorded? And in Black newspapers, you sometimes had just mentions of it or you even had mentions where you can correlate, You know, there was a lynching here or there was violence here, and you can potentially kind of read that with other partial sources to put together a larger picture because sundown towns did follow patterns.

I think it is hard, and I do appreciate that people look for, I guess, what historians call the smoking gun piece of evidence, the things that without a doubt proves that something happened. But history is just unfortunately messy. And sometimes while those don't exist, trying to kind of fit it into a larger, contextual piece of a puzzle is it can actually be successful. I think people can kind of try to put small pieces together to add up to something to something pretty definitive, even if they didn't have that photo of that sign. So one of my favorite questions to ask is where did the money come from? And I think that that's always a good question to ask in any type of dive into the past. Where did the money come from? Where did it go? Who got to control it? Who got to use it? And one of the things that most surprised me when I was researching the history of segregated suburbs was where that money came from, that financed the first planned segregated suburbs in the United States.

So with the case of Roland Park, Roland Park seemed on paper like it was a local, Baltimore-based company. And this is where you get sometimes the limits of a source or public records. It seemed like it was local, but actually it was financed by over 400 British investors who were actually putting their capital into another company based in Britain called the Lands Trust Company nice and generic. The Lands Trust Company was making investments all over the world in places that fit a certain mold, and that mold was where were White people moving to that would increase the value of that land. Now that may seem generic, but that's actually what then puts a segregated, planned suburb like Roland Park into the same investment portfolio as a settlement in the American West, that would have recently been the site of Native American Genocide. It puts it into the same investment portfolio as in British Caribbean, where people had profited from enslavement. And it put it into the same portfolio as British investment companies in the Congo, who were hoping that Belgium would open up trade in colonial Congo, which of course led to massive atrocities in the Congo.

So I was like, Oh wow, you know, by following that money and I traced it through its investors and through this sort of intermediate Lands Trust Company, I was able to realize that the segregated American suburb had a lot in common with things that people were conceiving of at the time as colonial and imperial. So there is a longer history thereof dispossession that didn't start with a racially restrictive covenant, but actually, that money that financed that house with that restrictive covenants actually came from, if you follow it back long enough, came from slavery and it came from Native American displacement and it came from British imperialism in Africa.

So what did that mean to me and what did that mean for American suburbs and American segregation? Well, it made me think about connections and generational wealth, so for instance, what does it mean when you can draw a straight line from slavery to Jim Crow housing segregation? It means that people who are making those investments had long been beneficiaries of money that came from racial violence and inequality. So that means that you can't necessarily disconnect slavery and say segregated suburbs, even though on the surface, they may not look like they were related. That money, if you follow it, connects them very materially and concretely.

Two, it made me think about American exceptionalism because suburbs, American suburbs, I think, can be seen as very, very American. That single-family house on the tree-lined streets winding on the edge of a city. I think that that's often even to this day in film and television, kind of depicted as an image of America. But what did it mean when those buildings and streets and forms have a history that connects them worldwide to racism, imperialism, dispossession? It means that American suburbs aren't so exceptional, but they're part of a larger story of a global Jim Crow in which I think there needs to still be a kind of global reckoning with how money can actually structure inequality worldwide and how one local manifestation of that is the American suburb.

![]()

Antonia Harlan

Community Leader

0:00

Antonia Harlan:

Chief Dial was coming into town, I think he came from Colorado, and I thought it was an opportunity to have conversations with the new person, right, who was coming into the new community and letting him know what is going on. Not getting the, you know, the whitewashed version of it or to say that it's cleaned up, I'm going to clean it up. And I'm not going to tell you the real truth. I'm going to tell you the truth I want you to hear. And so, what I wanted to do was sit down and talk to him and let him know, not the clean story, right? But the real story. And he welcomed me to come into his office. He hadn't been here long at all. Sat down and talk to him about it. And I said, It's not just me and my husband. You hear from friends and there were certain streets that were notorious where you get stopped on all the time and it's a profiling. And he made it known that's not what's going to happen while he's in charge. And so he started having these conversations with his officers, and he started to keep information about how many of the people that were being stopped, how many were African-American, right? So you have some evidence of that. And he started having these meetings with his officers, and I've been to meetings with his officers where we talked about race.

He invited me in to do that, which I thought was beautiful, to open the door for me to come in and have these conversations. At that time, I think there might have been one African-American on the force at that time, maybe one. And so I knew that he meant business, and I think I saw things change once Chief Dial was here, and once he came to town. I saw things change. Now, it didn't, wasn't perfect, right? And it still isn't, but it improved. He had an advisory board. He asked me to sit on an advisory board because he wanted to hear that, he needed that diversity and wanted that diversity. And I can talk about my community where maybe the people that were around the table couldn't. I could give you the stories about my community that you may not know about, but these things were happening then. They're happening now. It's not isolated.

If an African-American came forward every time they were discriminated against or someone who mistreated them. We would be doing that all day. We wouldn't have time to do anything else. So that's our life. I wish it were different, but that's our life. And so, you know, I tell myself and I told someone else this at a meeting. This person was running a group about race. This person was in charge of a group that were discussing race. And I said, You know, when I when I leave my home in Naperville, when I leave my home, I open my door and I go out. I'm going out into a world where I have to be... I feel like I have to be armed and aware of my surroundings of everything because it's not about crime in Naperville, it's about the discrimination, the racism.

![]()

Antonia Harlan

Community Leader

0:00

Antonia Harlan:

Antonia Harlan: At that time, I was focused on the kids, I wasn't really involved in the community a lot. At some point in time, I started paying more attention to what was going on in the community and I would go to a couple of council meetings over issues that concern me and realize that I had a voice that should be heard. And my children, because they were in a community that didn't have a lot of people that look like them, in my house at that time was kind of decorated with what I love the Asian furniture and that. And I had some Asian furniture and I thought, my kids, I want them to be grounded with their culture. And so I started making changes in my home. I still love Asian. I didn't take that out. So I started making some changes in my home decor and I did start decorating it multicultural. And I made sure that I included a lot of African art or African-American things because I wanted them to identify because they didn't see themselves in the community. Once they started school, they were usually the only African-American child in their class. And we also would, after they got a little bit older, we would, and my husband's idea, never forget this, that they would come to Detroit to stay with my parents during the summer.

We did that a couple of times. I was so resistant. I'm like, “No, I don't want to send my babies away!” And I can remember him, he said to me, “that's selfish because they need that.” And I wanted them with me. You know, I was a super mom kind of thing. And he said that's selfish. And I said, you know, you're right, you're right, because they need that, they need to be around their cousins, they need to be in a community where they see themselves. They need to be with their grandparents. You can't teach them this in a book, and I wanted them to know it, to feel it, to smell it. All of that, right? So they went to Detroit, as I said before, I always just wanted to be a mom, you know? And so I really love those years of my kids being small, and being a mom, and then they go to school and then they become latchkey kids and all that and a little bit more freedom, and they don't want you around all the time and in their face. And so I get at that point, I felt I could get out and do some things. And so I think I first started with some issues in the city and I would go to City Council meetings and speak up about things that I was concerned about.

And there was a group of women, African-American women, who thought the same thing about the school district, that the diversity wasn't there and how it affected our kids. And so I met with this group and we were sharing ideas, and they had some ideas about bringing more diverse teachers and things like that into the school district. And I thought, well, their concern was mainly African-American teachers, and I thought diversity in general is good for our kids and African-American, of course, but other cultures as well, because we can all learn from everyone. And so I kind of, that's when I start thinking about the diversity here, and what are kids gaining from not being a part of the diverse environment? And what are they going to do, not just my children, what are these kids going to do when they leave Naperville, when they go to college and they may end up in D.C. or New York? I mean, goodness they would be shocked because they wouldn't know how to even manage being around people from all different backgrounds. And I thought it was really cheating our kids, not having that. The teacher issue was monumental. And it still is. I can't believe that even today we're still talking about the same thing that we still haven't reached that in Naperville. I was looking through some papers I had, back then we were talking about diverse teachers. We still don't have that. How many years ago was that?

And so I felt that educating our kids, we have to look at them in a holistic way, not just, you know, intellect. But there's so much more to being a human being. And so if I could maybe give them that other piece or introduce them to that other piece, it would help them be well-rounded individuals. And so I started this committee, multicultural awareness committee, and I have individuals from Naperville from different cultures. I think at one point, I look, there's some reference papers, and I think it was about twenty-five members, multicultural awareness committee and we all had the same ideas. And we were all from different backgrounds, different cultures. And so we started doing work in the community. We would put on galas. We had a number of multicultural galas where we would have people from different cultures come in to the schools and they would perform and then the kids would get to see them and talk to them and so forth. We had international children's concert where we were just all little bitty ones from different cultures showing off their talents. You know, one played the piano, one played the flute or one did Irish step dancing and kids could see that, the community could see that. So we had a number of galas and concerts, and we even had multicultural fairs where cultural groups could sell their wares. We had that at Fifth Avenue station.

And so it was my way. And then I started going into the schools and talking to kids, about cultures, about my culture, about African-Americans, about other cultures. And I started collecting artifacts. And it was a way that, you know, because people learn different ways. And so some learn by sight. Some learn by touch. And so if a child, I even had music incorporated into this exhibit, and it was music from all different cultures, and I would tell the teachers, if you use this music, have some music playing when the kids come into the room, maybe it's Vietnamese music, maybe it's Greek, but let them listen. You don't have to let them listen long, let them listen for a little while and then see if they can identify what it is and if they can't, tell them this is from Greece. And then they start to appreciate not just what they know, but appreciate what they don't know about.

And so I had a collection of music. I had a collection of artifacts and I would go into the classrooms and I would pick some of the items out and I go to the classroom and talk to the kids about it. And it was amazing, and I knew that that's what I was supposed to be doing because the kids were so receptive. I never had any problem with any kid about anything that was presented to them. They were all happy and excited and interested and had questions. And I don't claim to be an expert on any of it, but we can all do something, you know? And that, to me, was what I should be doing is to try to get them to see what I saw as a child, which was that there's beauty in other people, in other cultures, and you can learn from them and you can be friends with people and and then you find out they're like you, you know, their mom calls them in for dinner, just like my mom's calling me in for dinner. Or, you know, or they have a little wading pool in the backyard and they want me to come over because I'm their friend and doesn't have anything to do with what color I am. And we can play and we can have dinner together and we can go out together and do these things. And so I wanted them to see and learn the way I did.

And so I start collecting pieces, I didn't have any money, but I would go to resale stores or antique stores and just browse around and see if I could find anything that was cultural and I would buy it. And if any of my members at that time were if they were going to travel or something, I said, Can you bring me something back? And they may bring me a little figurine or whatever, and I put it in the exhibit and make sure their name was attached to it. So that's kind of how that, and it ended up being 100 plus items in the exhibit. So once I was doing that and going into the schools and taking pieces and then talking to the kids, when I went back to work, it was more difficult to do that. And so I wanted, but I didn't want to stop. I knew the kids were really benefiting from it. And so I left the school district use the exhibit and the teachers could use it for their students in that. And so they would use it to take it around to the classes and other organizations. NAACP, they would ask for it certain pieces, and I would let them borrow it and so forth.

Interviewer: So how did this work with the school district and with the schools? Did you have people who were helping you champion this within the district? How was that all, how did that piece work?

Antonia Harlan: Well, it's amazing. You know, I think back on the time when I started doing this, which is roughly 30 years ago, and I remember that, that said, “there's a time in the season for everything,” right? And I know that there was some resistance from something they just didn't see the importance of it, some people didn't see the importance of it is like it was before its time for them, wasn't before it's time for me, but for them. Their minds didn't see the importance of it. And so I wanted to be in the schools, and I went through, I met Mary Ann Bobosky. She worked in the superintendent's office. She was in an administrative position there. Awesome, awesome person. And I'm so grateful for her because she championed it. She said, “this needs to be here. It was important.” She always let me know that it was important, and that she would do whatever she could to make sure that I had an inroad into the schools. And honest to goodness, I don't know anybody else who was able to do that, but she got me in the schools. If I called any school or any principal, whatever, it was a “yes, come.” And it was because she opened that door for me.

And so then they would call me, and they would say, “Can you come out and speak to the students?” Or whatever, and it was because Marianne was that champion for me. And because of her doing that, the superintendent was just as open and welcoming. And that's how I ended up coming through into the District 203. But I also worked a little bit in District 204 because, you know, the word travels. And so they had the exhibit for a number of years. And Mary Ann, there was not one person who was really taking real responsibility for it, as to making sure that you let things out. It came back or in how it was handled and so forth. And I wanted it to be hands-on because I felt the kids needed to touch and feel, not just see it in behind a glass. So Marianne told me that, you know, that I probably should get the exhibit because she I think she thought some things might have been missing and broken or whatever.

So we brought it back to my home and did an audit. My kids did an audit on it. And in fact, there were some pieces missing and some things broken, and it stayed at my home after that. But leading up to that time, I just had all these things in my dining room, on my dining room table, and I can remember my kids say, “Are we going to have Thanksgiving in the dining room this year?” Because it was a museum at that point, you know, it was like all over the table. I was like, “No, I guess we're going to have it in the kitchen.” And so they were like “are we going to have Thanksgiving in the dining room?” And she came out to my home, her and one of the superintendents and, not superintendent, one of the principals, and they looked at the items and so forth. And I said, I needed cases for them so that it was the easy way to move them around, move the items around. And I designed these cases and I couldn't get funding for them. And there were some newspaper articles about still waiting on funding for the multicultural exhibit, and I couldn't get funding for it and I'd wait. And then I tried again and I couldn't get funding. And finally, I went to the City Council about it. And long story short, they approved funding for cases. And at that time, I had redesigned the cases from what I initially wanted, and ended up designing these plastic trunks that had separators. And so you could put items and wrap them in wrapping paper and put a separator, put some more items in that. And so they did. They approved the funding for the cases, and that's how I got those. And Jack Tennison was at that time was on the council and he was very instrumental in supporting it. He was a great supporter for that.

Interviewer: You're working around the concept of community policing. You're a mom, you're a wife, you're a daughter. You also start writing. You author. You authored books. So I don't know which. And you saved somebody's life, you know CPR, right? This is only what I know. So let's talk about each of those things. And I don't know what order we want to attack. Maybe you want to pick or I'll just shoot out a topic and then you can talk a little bit about it. So let's talk. You start writing books. How did that come about?

Antonia Harlan: OK with the books? I think the first book came and I had a concept of what I wanted to do after the first book, and the first book came. “Hello, my name is Josie Mae Bricker” about a little slave girl growing up on a plantation in Georgia. And I think initially it was a little scripted thing that I did when I was presenting to the schools. So I wrote up this little snippet. And when I would want to talk about African-American history or something, I would portray this little girl. So I would put on a, tie my hair up in a scarf and put on an apron thing and I'd have a little basket and I would put cotton balls in it like it was cotton. And I go out on stage and it was just a small snippet of Josie Mae, and I would talk to the kids as I was this child. And after I did that and was so well-received, I thought I should make it into a book. So I expanded. I expanded the story much further than what I would do at the schools. And then I thought, oh, I wanted to do a whole series of cultural of kids, and they were all being called, “Hello, my name is...” and it would be kids from different cultures and giving their stories because, once again, I think kids learn when it's another kid and they can identify.

And so I did her book, and then I did another book. “Hello, Shalom. My name is Sasha Feinstein” a little Jewish boy. And it was very expensive to publish. Even self-publishing is very expensive to do. And so, and then I was working full time. And so then life got in the way. I guess so I never got, I had blocked out several other books, but I never actually got them to publication. And so I have the two books, Josie Mae Bricker and Sasha Feinstein. And when I did a lot of research and I wanted to include a lot of factual things in the book, so while you're learning and enjoying, you're also learning something about their culture or something about history or that. And so that's how each book is designed. So when I was writing the book on Sasha Feinstein. I'm not Jewish, so I thought I can do a little research. I had a friend who was Jewish. I could talk a little bit to her about her, how she grew up, or her family, and get a little insight that way. A little historical research to add that. But once the book was finished, I wanted to still make sure that I wasn't making assumptions about someone else's culture. And so after it was completed, I let a rabbi look at it and ask him to critically look at it and make sure that I wasn't overstepping on anything or making mistakes on anything. And he made one small correction, which was some language that I was using that I thought a child might use this language and say a word in a certain way as a kid. But he said no, because a Jewish child would know probably the correct way, and they would not make it cutesy or something, you know? so I took his advice and I changed that, and so that's how that book was completed.