Local Spotlight

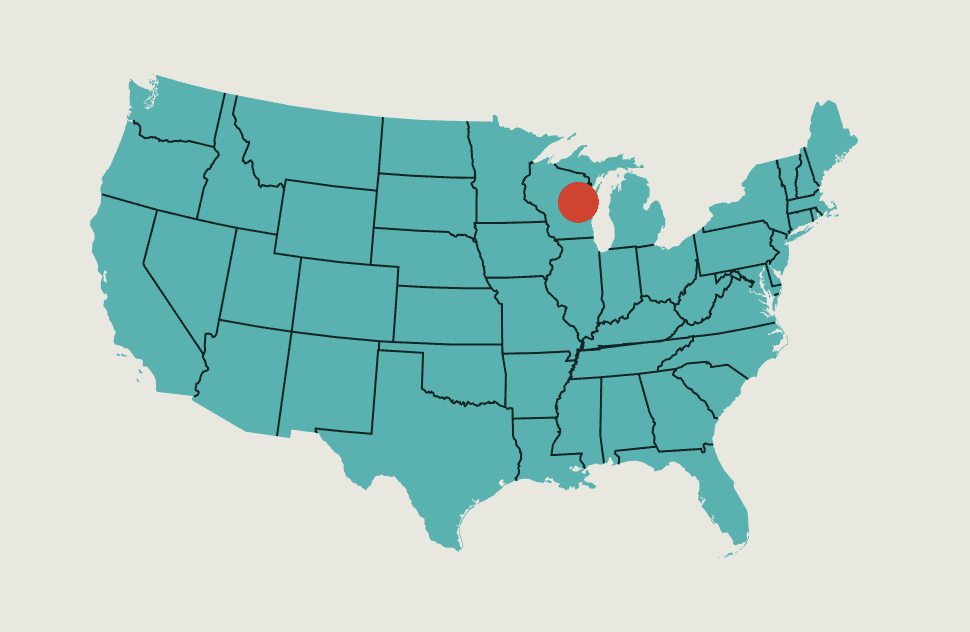

Appleton, Wisconsin

Courtesy of the Oshkosh Public Museum

Community Profile

- Community: Appleton, 1847

- County: Outgamie, Calumet, and Winnebago

- State: WI

- Type: Urban

- Metro: Fox Cities

Appleton is on the ancestral homelands of the Menominee and Ho-Chunk. Today, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin is located north of town. The fur trade brought Europeans and Africans to the region. Later, the French and Americans would bring enslaved Africans with them to the western Great Lakes. Appleton was settled as three unincorporated villages in 1847 and they merged to become the Village of Appleton in 1853. Early White settlers predominantly included Germans and Yankees. After the Civil War, a growing Black community flourished in Appleton, with hundreds of Black people living in the broader Lake Winnebago Region. By 1930, this community was driven out by harassment and violence. In more recent decades, immigration of Black, Hmong, and Hispanic people again changed Appleton’s demographics.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 65.6%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $147,800

- Median Gross Rent: $808

- Median Income: $58,112

- Poverty Level: 10.8%

- High School (ages 25+): 92.5%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 33.4%

From The “Free Air of Liberty” to Sundown Town — Stories of Resistance and Resilience

The story of Appleton, WI, demonstrates how residents of color maintained their determination to claim space despite significant discriminatory obstacles put in place by White residents. Black people were forced out by sundown townSundown Towns: All-white communities or counties that purposefully maintained their status through harassment, discriminatory laws and ordinances, and violence or threat of violence. The name comes from posted and verbal warnings that Black people and other people of color would receive upon entry. Sometimes this status was codified in law and signaled with signs, sirens, or other warnings. Often, laborers such as household, farm or factory help could work in a community during daylight hours and had to leave town by sundown. Frequently, it was maintained by practice and custom of local people and law enforcement. Sundown towns appeared in many areas of the nation between 1890 and the 1970s with some still maintaining their all-White status. customs, restrictive covenants,Restrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group. and other exclusionary practices. Police used an anti-vagrancy ordinance to exclude and harass Black residents and Oneida people from the nearby reservation. Ultimately, these tactics would reduce Appleton’s Black population to zero. By the mid-twentieth century, a new Black population grew into a supportive community that fostered resilience in the face of targeted discrimination.

After the Civil War, many of the Black people that moved into northeast Wisconsin founded small businesses and pursued professions like education, forging a sense of community. A group of Black citizens who held positions of status in Appleton referred to themselves as the “Black Aristocracy.” In 1899, Mary Cleggett, a Black resident of Appleton, described Wisconsin as having the “free air of liberty” in a letter published in the Wisconsin Weekly Advocate, a Black newspaper based in Milwaukee. African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Churches in nearby Oshkosh and Fond du Lac were centers of Black community life—both cities had Black populations over 100 before 1910. In 1913, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Oshkosh celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Emancipation with a festival. Today, this tradition has been reestablished in northeastern Wisconsin with large JuneteenthJuneteenth Day: Juneteenth Day (also known as Jubilee Day, Emancipation Day, Black Independence Day, and Juneteenth National Independence Day) commemorates the announcement of emancipation of Black American enslaved people in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865. Texas was the last state of the Confederate States of America with institutionalized slavery. On June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden declared Juneteenth National Independence Day a federal holiday. For many Black Americans, Juneteenth Day celebrations hold more significance than Independence Day. celebrations.

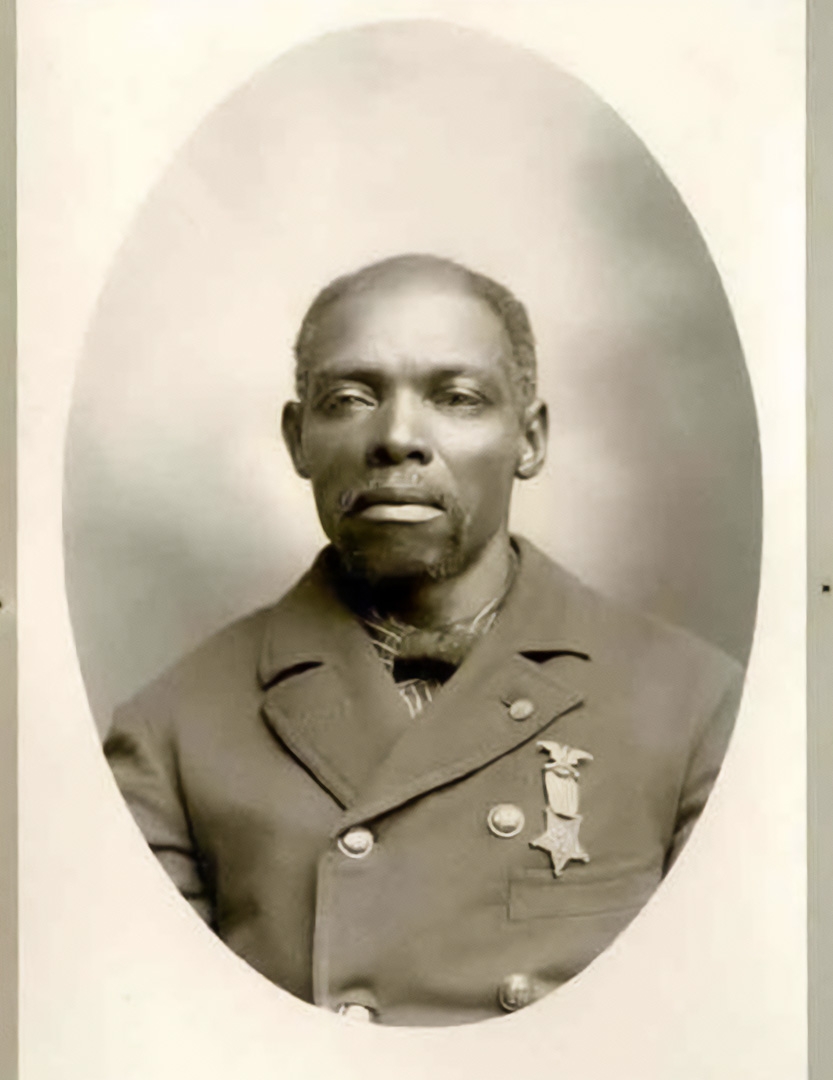

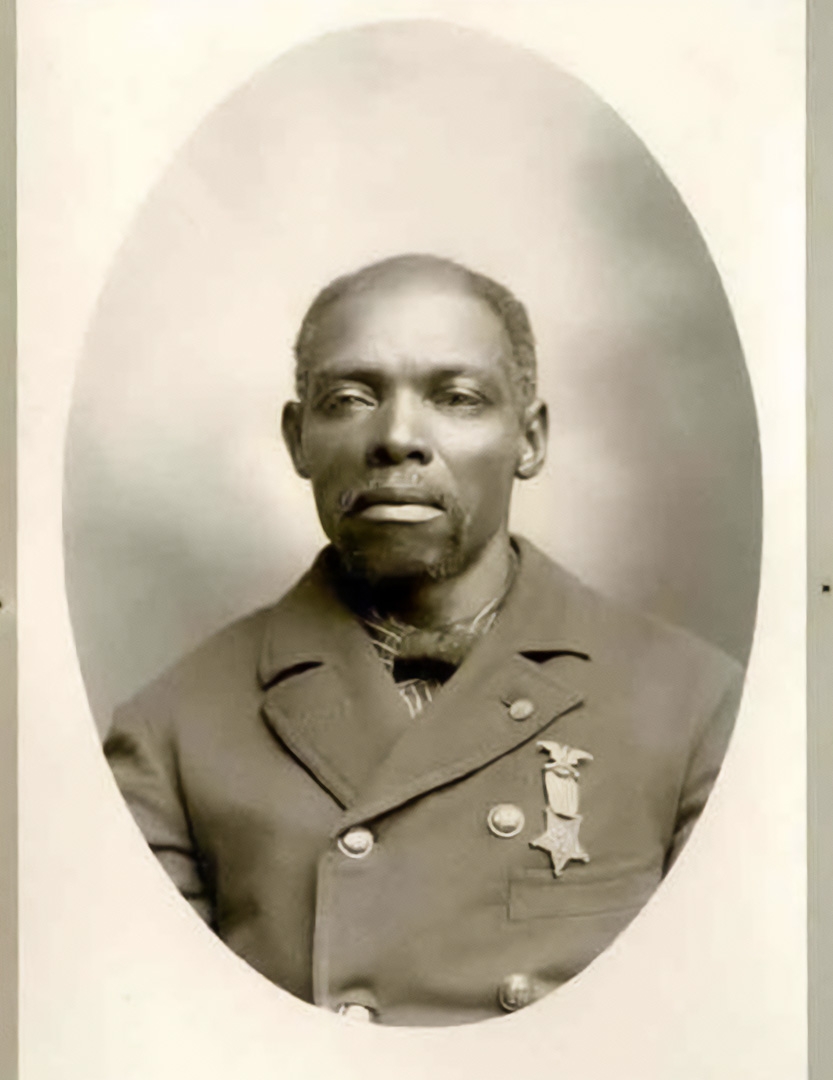

Appleton resident Horace Artis, in his official portrait for the George Eggleston Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. GAR members fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Courtesy of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum

Noted Black chemist Dr. Percy Julian declined a position at the Institute of Paper Chemistry in 1935 due to the community’s sundown customs. Tensions increased during World War II when Appleton employers facing worker shortages and a federal farm labor program provided laborers from South Texas, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica temporary work assignments. These Black laborers were required to live in a tar paper barracks provided through the program and moved on to their next work assignments after harvest and canning was complete. They all knew that when the jobs were done, they would relocate to another place that needed laborers. In 1946, Appleton’s Riverview Country Club rewrote their deedsDeeds: A deed is a written legal document which identifies individuals and other entities that have a claim to a property. Deeds are commonly associated with transferring property titles. to deny Black people the opportunity to purchase homes there. In 1952, local factory owner Victor Bloomer refused to hire Black people because of an “unwritten law that evidently keeps negros out of Appleton even for an overnight stay.”

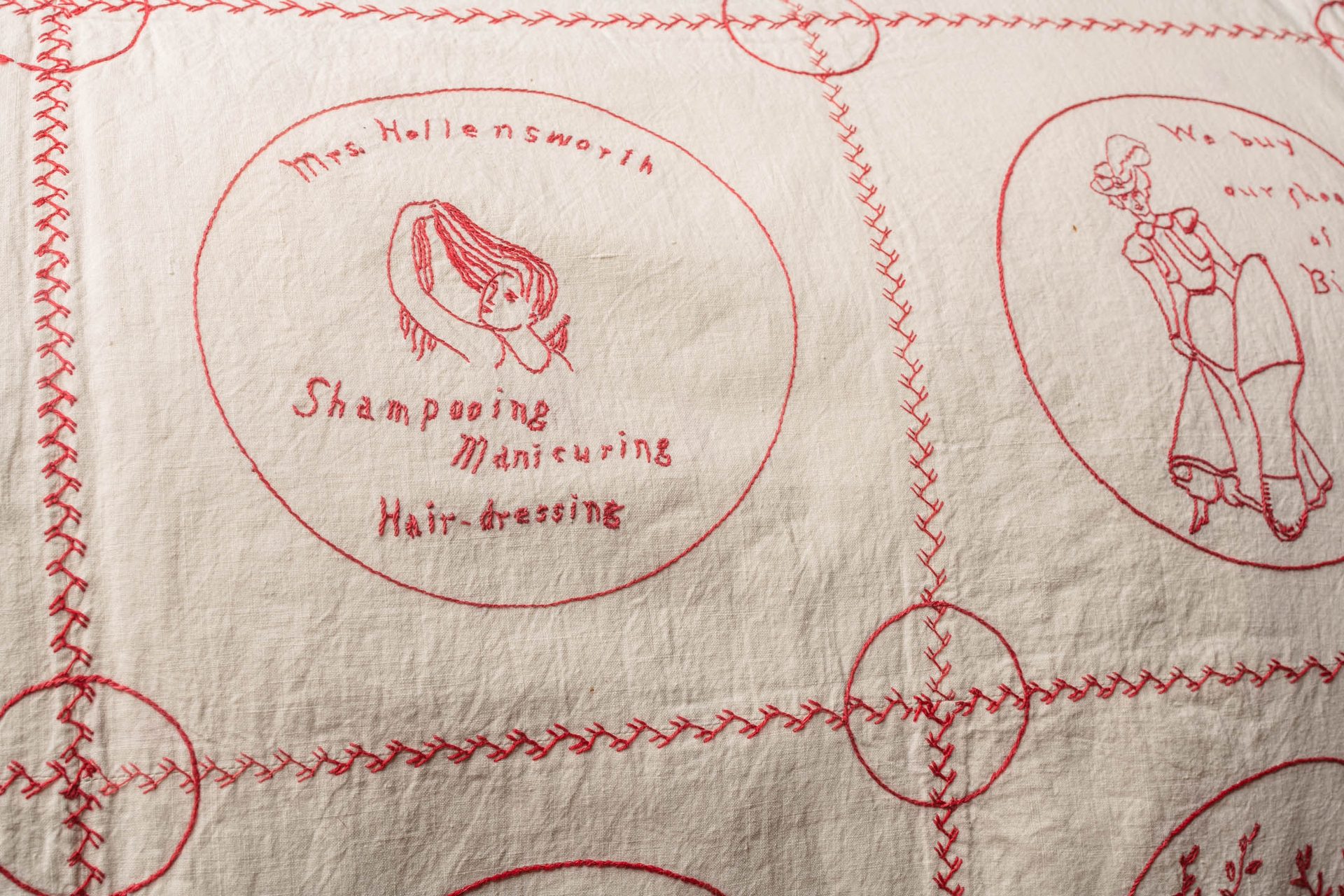

As part of the "Black Aristocracy", women like Emma Elmore and Gertrude Louise Hollensworth built a community around what Mary Cleggett termed the "Free Air of Liberty."

The Wisconsin Weekly Advocate

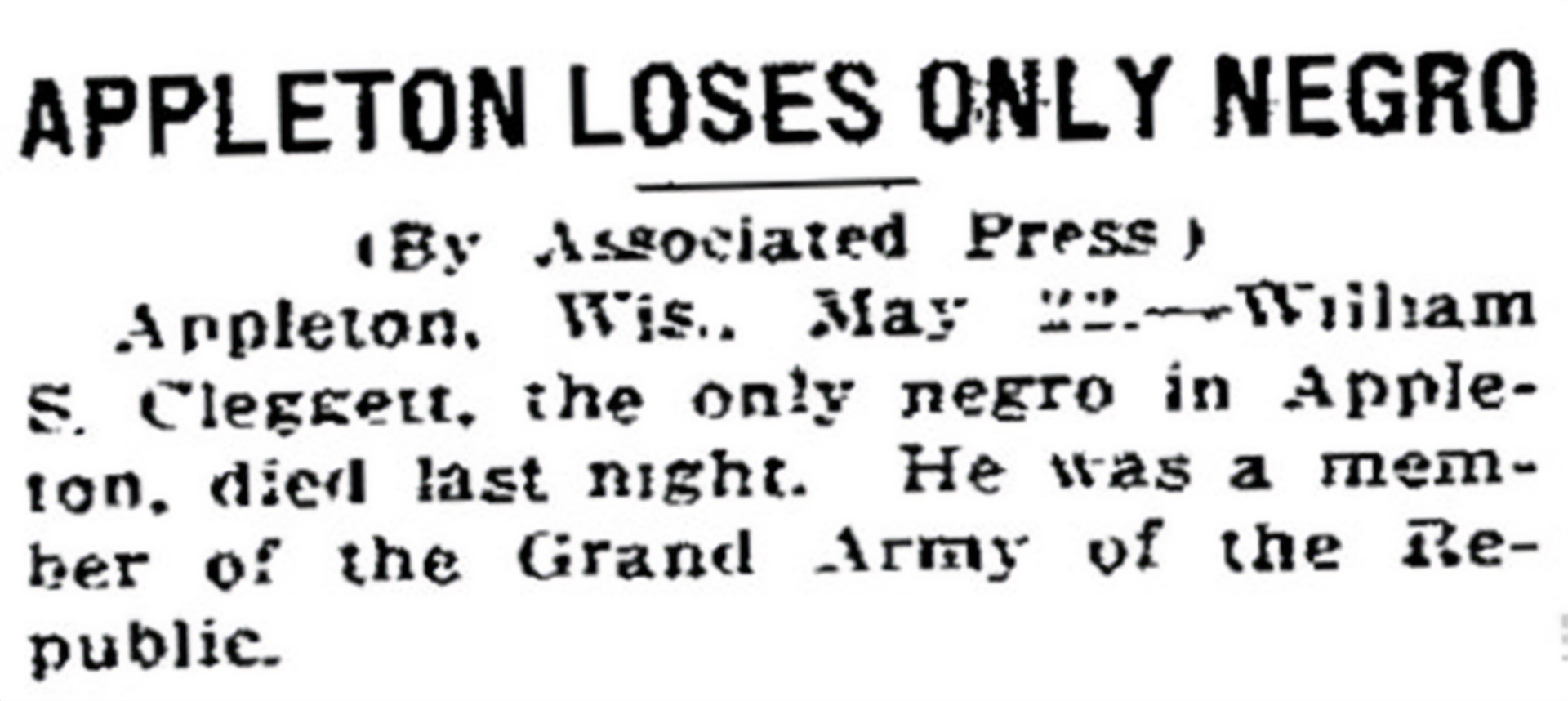

Despite their deep roots in the area, by the late nineteenth century Appleton’s Black residents confronted a rising tide of discrimination and violence. Racial harassment was pervasive. Black residents were not allowed to patronize many local businesses and known homeowners were arrested under vagrancy laws. The Black population declined to zero by 1916.

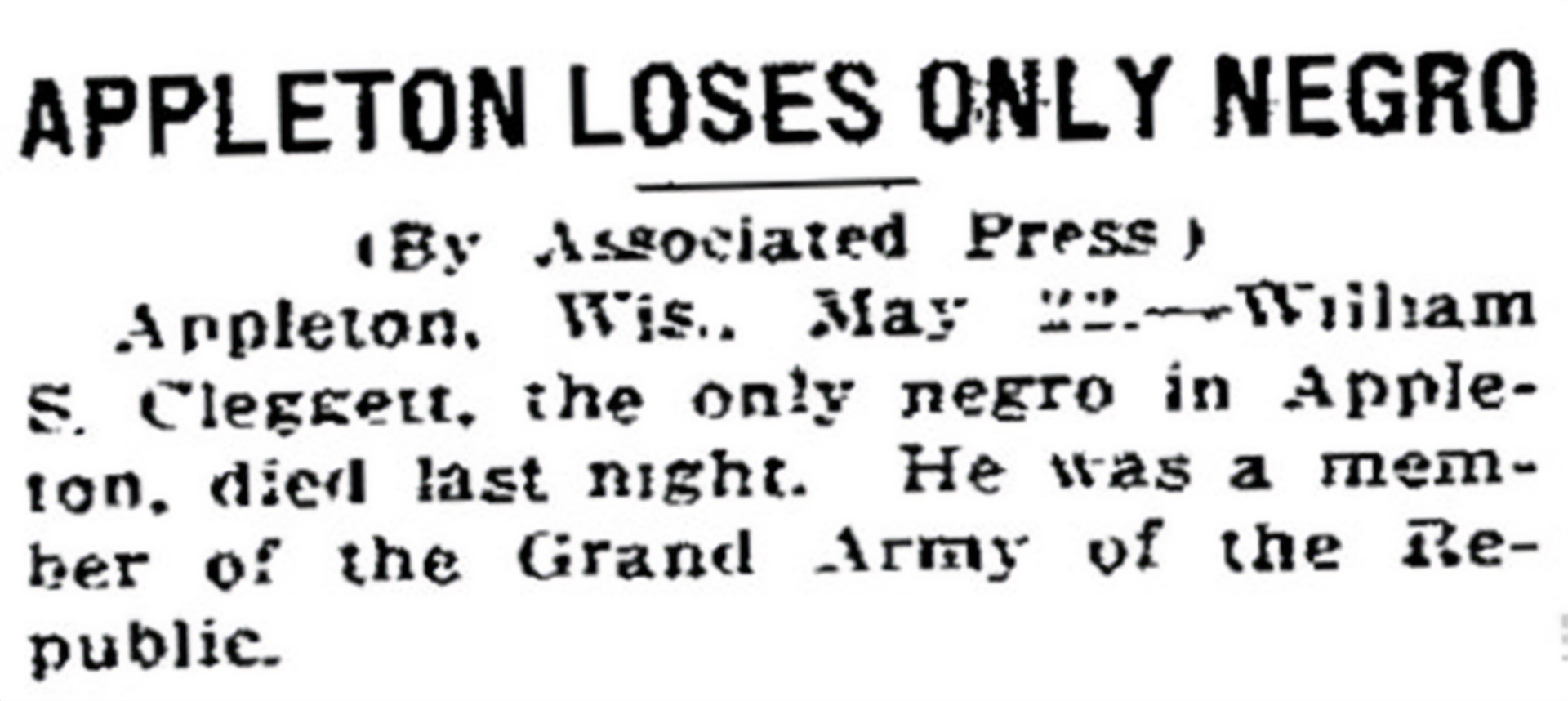

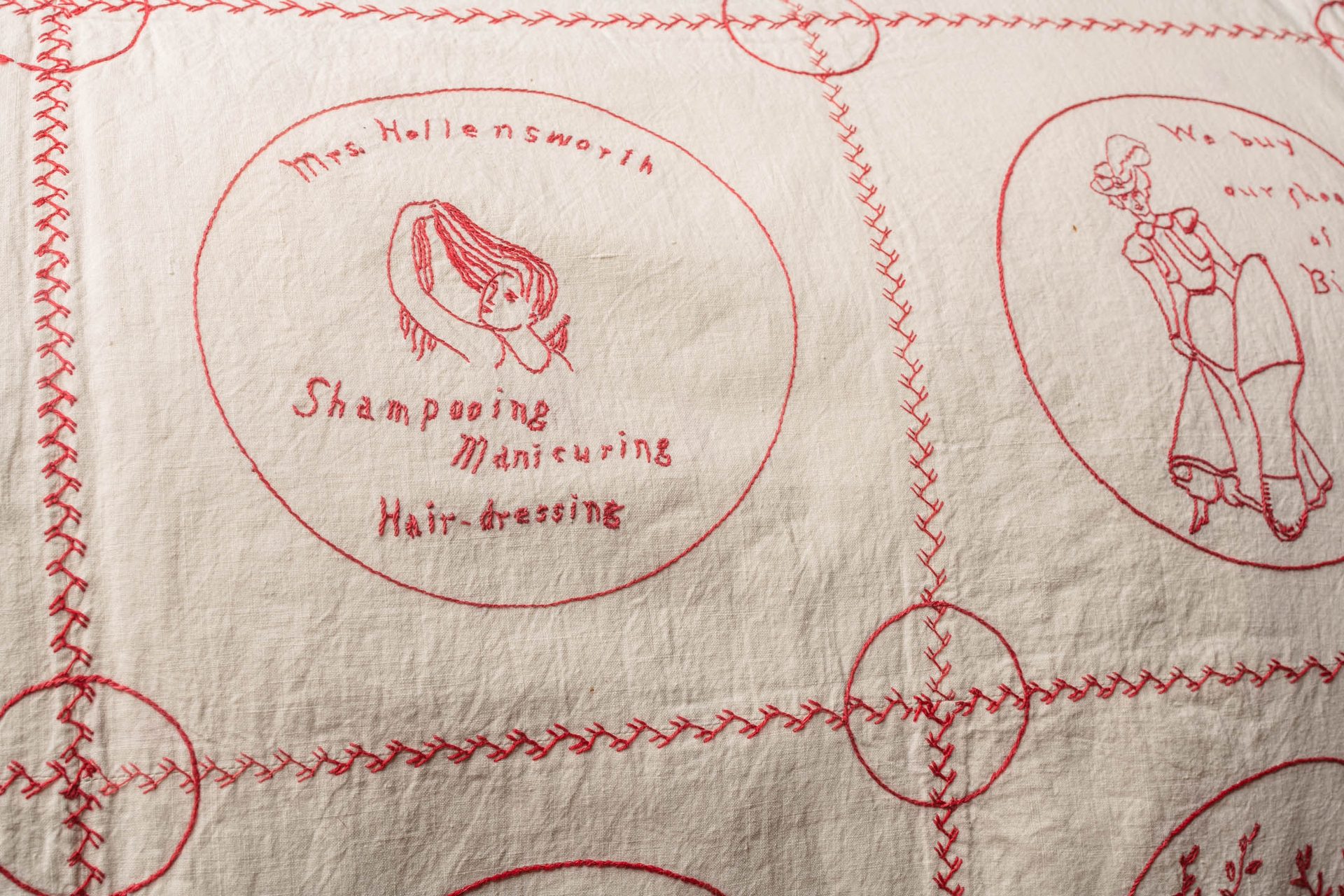

In 1916, Oshkosh Daily Northwestern reported that after the death of resident William Cleggett, there were no longer any Black people in Appleton.

Courtesy of the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern

By the 1920s, sundown town customs were so widespread that many White residents assumed Appleton had an official ordinance. In 1923, local White residents formed local chapters of the Ku Klux KlanKu Klux Klan (KKK): An organization founded in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1865 with the most violent and aggressive reaction to Reconstruction and the freedom of Black Americans. The Klan committed acts of domestic terrorism against Black Americans and northern sympathizers including physical and psychological intimidation, cross burnings, and lynching. The Klan attempted to prevent Black Americans from participating in social life and promoted the superiority of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans. There have been many resurgences of the Klan, most notable in the teens and 1920s where the revived Klan as well as the Women of the Ku Klux Klan attracted mainstream Protestant Americans such as elected officials, law enforcement agents, ministers, and housewives to the organization. The 1920s Klan had members across the nation and Klan targets expanded to Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and others considered enemies. (KKK) in communities throughout the Fox Cities. The effort to maintain Appleton as an all-White city reinforced racial discrimination at the individual and institutional levels.

Embroidered on this redwork quilt made by Teresa Wagg in 1900 is "Mrs. Hollensworth Shampooing Manicuring Hair-Dressing" promoting a Black-owned business. Business owner Emma Hollensworth also worked at the Appleton Children's Home as a matron. Her daughter, Gertrude Louise Hollensworth, was a school teacher. They were part of the "Black Aristrocracy" of Appleton.

Courtesy of the History Museum at the Castle

The Chicago Defender occasionally promoted the region as an outdoor recreation destination for Black Chicagoans. Black tourists, however, faced segregation on the road. They could not stay in most White-operated hotels, eat at White-owned restaurants, or rent cottages in White communities.

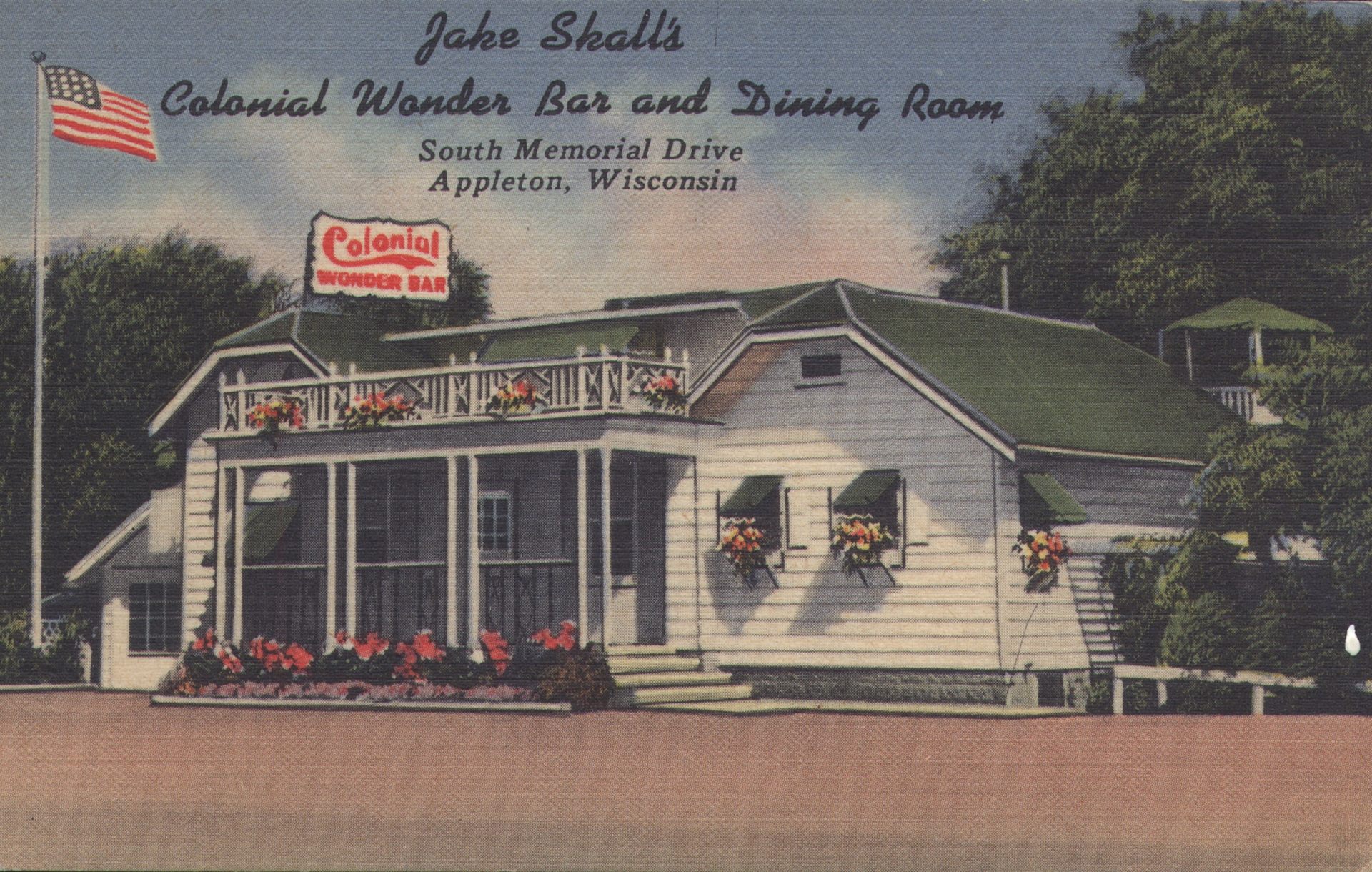

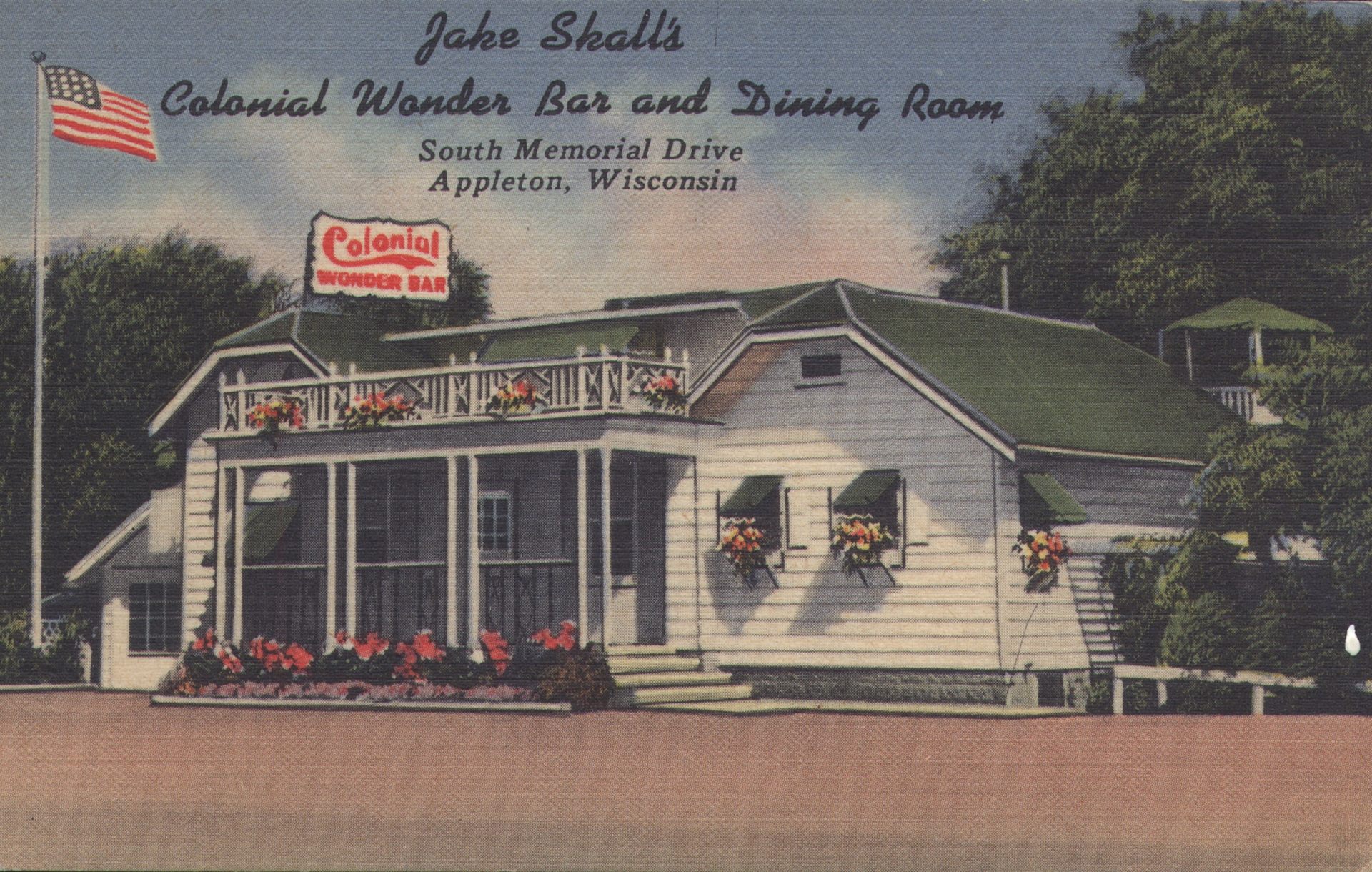

Access to Appleton hotels was severely restricted starting in the 1910s and continued to pose a problem for travelers. On a visit to Lawrence University in 1941, concert singer Marian Anderson was able to stay at the Conway Hotel in downtown Appleton but had to eat in her room to keep her presence unknown to guests. Seven years later, Lawrence student Rosalie Keller documented restrictive policies at businesses, restaurants, and hotels in Appleton, including the Conway Hotel and the supper club Jake Skall’s Colonial Wonderbar. Keller encouraged resistance.

It is our duty as world citizens and decent people to do something, right now, about this very important problem. Whether it is by boycotting restricted places or by speaking and crusading in our own communities or by just not sitting back and letting people talk in bigoted, narrowminded terms about the ‘ni**er,’ I don’t know. But we can’t be passive any longer.

—Rosalie Keller, Student

At Jake Skall’s Colonial Wonderbar, Black people were required to order from the back door on the outside of the building.

Courtesy of History Museum at the Castle

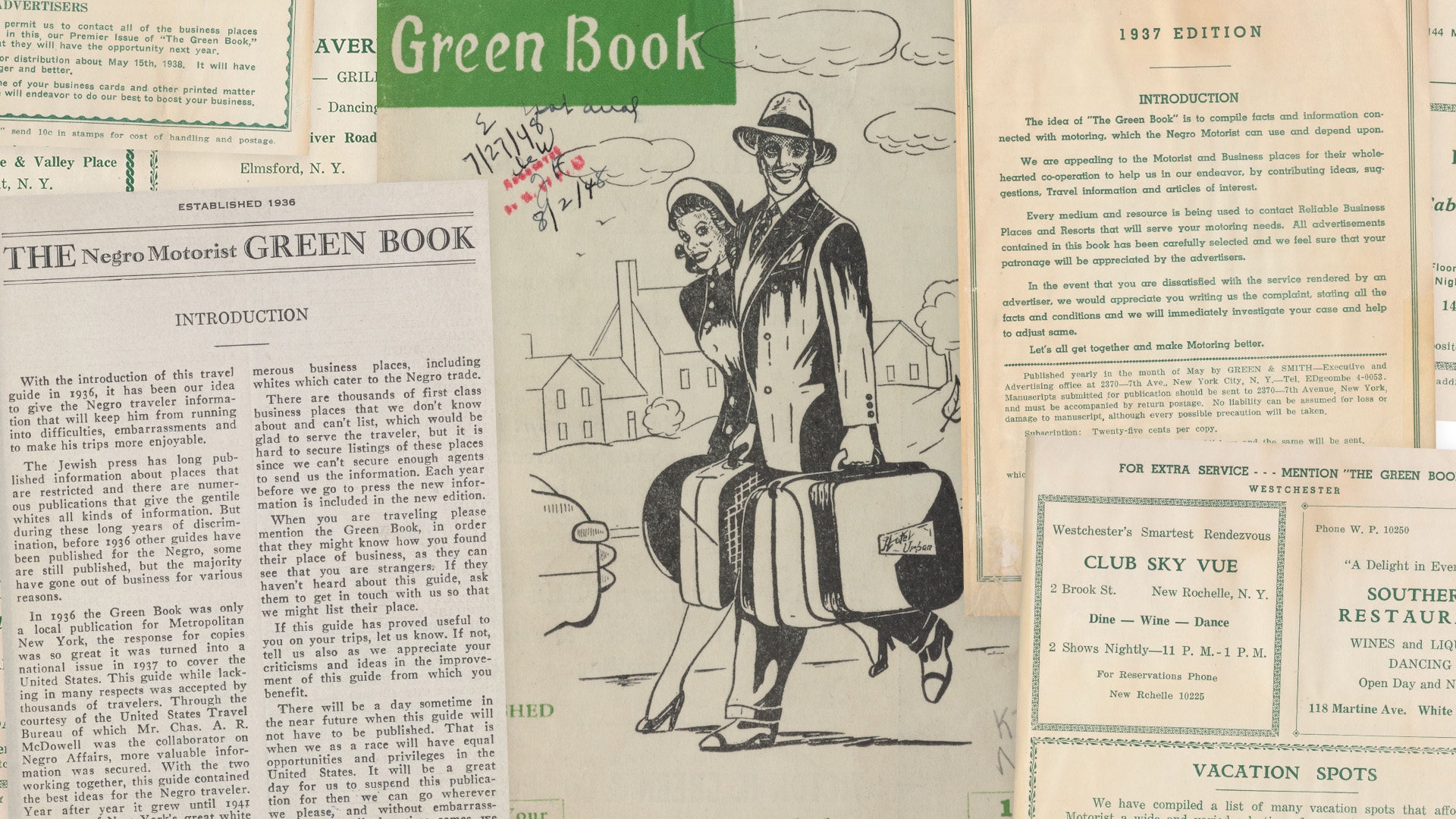

In the face of segregation, Black tourists relied on the members of the established Black community for safe passage. Motorists from Milwaukee used the Negro Motorists’ Green Book to plan stops at Black-friendly tourist homes in Oshkosh and Fond Du Lac, both operated by Black women who were among the last community members from the early Black settlements, and one hotel each in Oshkosh and Green Bay. The tourist homes and their residents were often subject to excessive policing.

Resource

Green Book locations in Oshkosh and Fond Du Lac represented efforts by the last of the early Black settlers to continue making the region accessible to Black travelers.

Local White support for segregation remained strong.

The Fox Cities formed a regional chapter of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in 1923. This rally in Oshkosh in 1925 illustrates the popularity of the KKK at that time.

Courtesy of the Oshkosh Public Museum

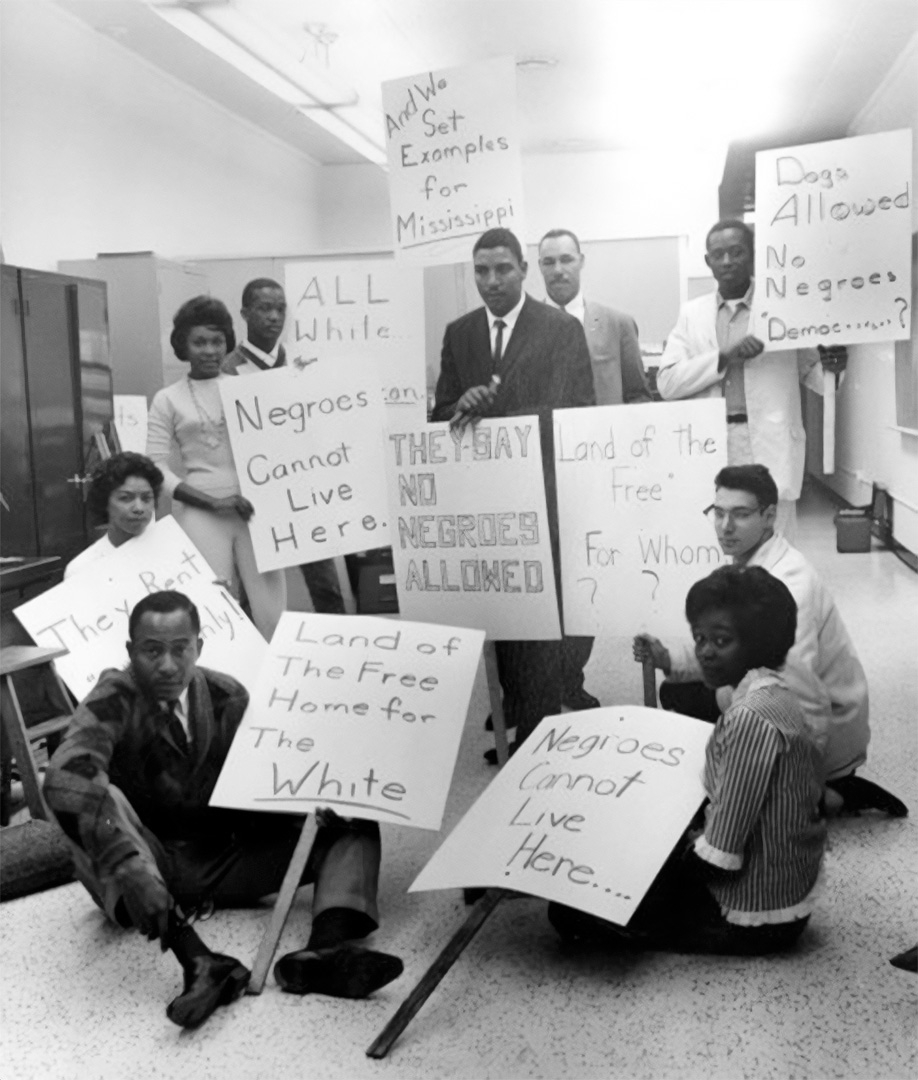

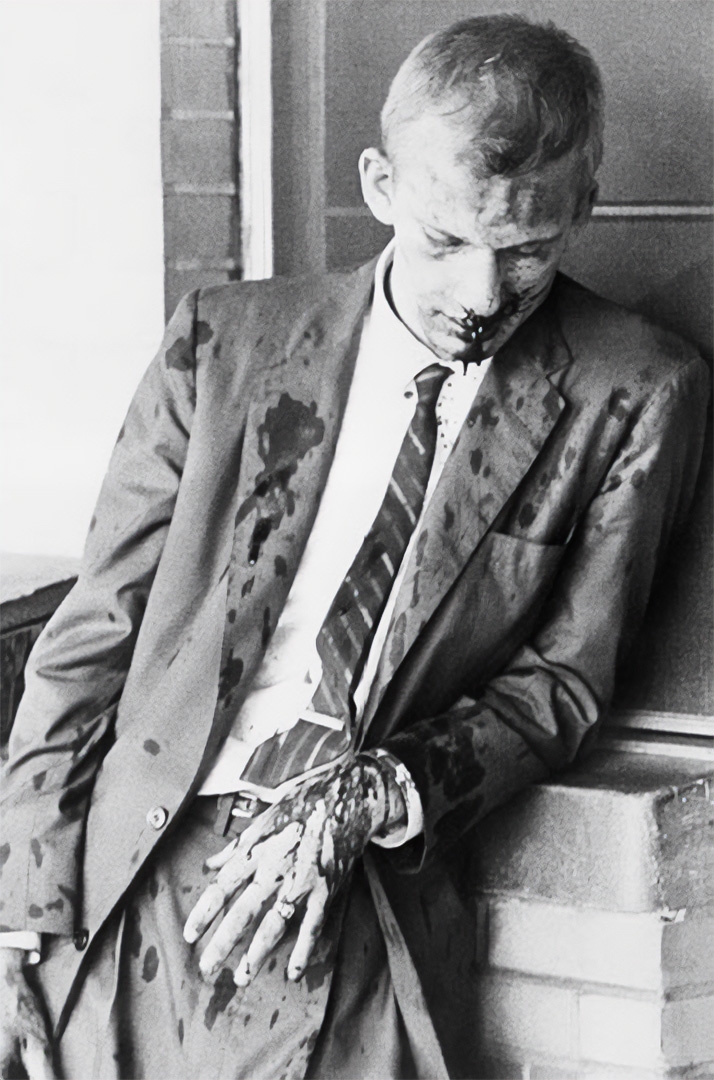

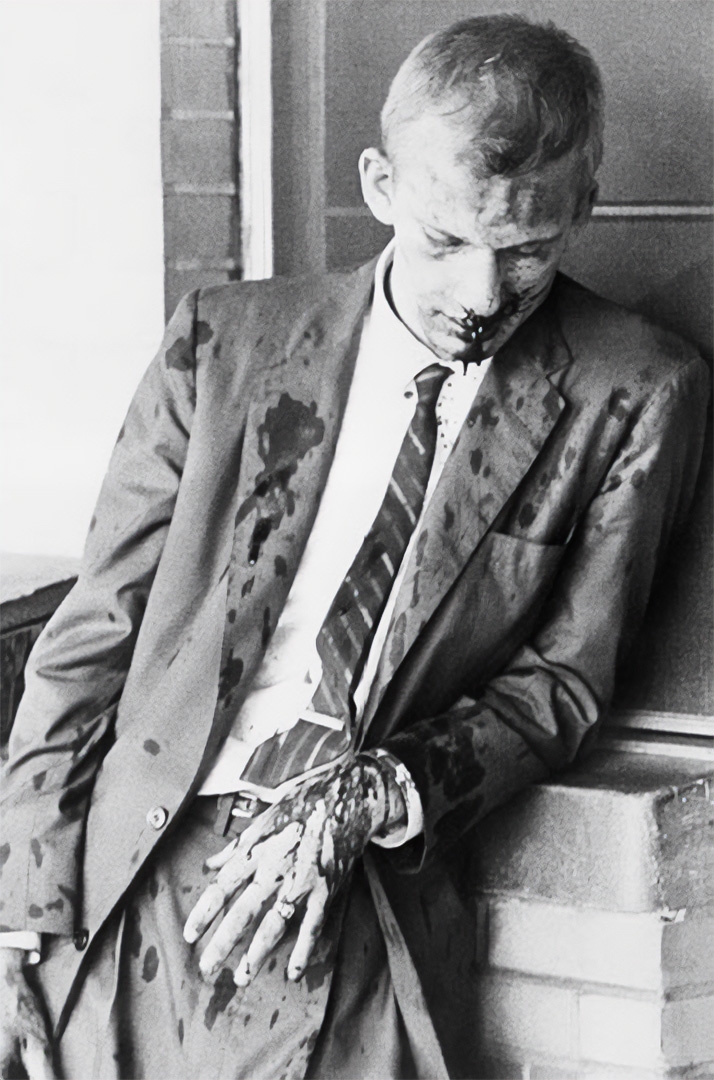

In the spring of 1961, 21-year-old White Appleton resident Jim Zwerg joined civil rights activists in the Freedom Rides to challenge segregatedSegregation: The act of separating people based on race, class, or ethnicity enforced through legal means or customary practice. travel in the South. Zwerg described his hometown as “lily White Appleton,” recalling no persons of color living in the city during his childhood. On May 20, 1961, Zwerg was violently beaten in Montgomery, Alabama. His attack sparked renewed conversations about segregation back home in Appleton. In 1964, Alabama Governor George Wallace launched his presidential campaign at the Appleton Rotary Club, during a special invitation event at the Conway Hotel. Wallace was famous for his rallying cry “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Local White support for segregation remained strong.

Appleton resident Jim Zwerg was battered and bloodied while participating in the 1961 Freedom Rides in Montgomery, AL.

Courtesy of Corbis Images

Starting in the 1960s, Black residents began returning to the region known as the Fox Cities, which included Appleton. Among the most visible Blacks were students. Lawrence University joined a growing number of mostly White campuses in the 1960s in recruiting students of color. Prominent civil rights activists joined with student leaders to demand change. In 1967, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited the University of Wisconsin at Fox Valley and spoke about discrimination in housing and employment. The local newspaper reported on Dr. King’s visit:

“I am sure that Negroes could get along here if they were sure they could get good jobs” and would be granted privileges equal to those of others in the community, he said. “Such an effort, he added, would help fill local employment needs while relieving the crowded conditions of large city slums.”

It is our duty as world citizens and decent people to do something, right now, about this very important problem.

Ella Fitzgerald is intentionally photographed for the Appleton Post-Crescent in 1961 having breakfast at the Conway Hotel to illustrate more open access to Black people.

Courtesy of the History Museum at the Castle

King’s visit fueled protest against racism in Appleton. In July 1967, the Appleton Housing Authority was established to address the need for housing for low- and moderate-income families. After Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968Fair Housing Act (Civil Rights Act of 1968): A Congressional Act that protects people from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, religion, disability, and familial status when renting or buying property or applying for a mortgage., Appleton finally enacted its own fair housingFair Housing : The assertion that people ought to determine the roof that they want over their heads without unlawful discrimination based on race, age, sexual orientation, religion, ability, or any other protected class. Commonly referred to as open housing in the mid-twentieth century, the fair housing movement and racial integration in communities were core demands of the Civil Rights movement. ordinance.

Students advocating for racial equality picket outside the Lawrence University Administration Building in 1972.

Courtesy of Lawrence University Archives

By 1970, some companies headquartered in Appleton, like Kimberly-Clark Corporation, began recruiting people of color to their workforce. The African American Employee Network, founded in 1990, continued to support Black professionals working at Kimberly-Clark. As job opportunities for Black workers expanded between 1980 and 2010, Appleton’s Black population grew from just 31 people to 1,179.

Organized by African Heritage Inc., Appleton's contemporary Juneteenth Festival began in 2010. It has grown to an annual attendance of thousands. Congressman John Lewis was featured speaker at the 2018 event.

Courtesy of African Heritage Incorporated

Residents of color in the Fox Cities continue to face disparities in employment, housing, and education. According to a 2013 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing submitted by the Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council, “Appleton’s Black and Hispanic populations are more integrated than other Wisconsin communities; however, the segregation of the Asian and Native American populations in Appleton is relatively high.” The 2019 City of Appleton: Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing report highlighted continued issues, stating:

"Persons of color received a disproportionately low share of loan originations. Lending discrimination can be subtle and sophisticated and may be embedded in credit and institutional policies. These factors can make it very challenging for borrowers to recognize discriminatory experiences, which leads to underreporting of unlawful discrimination in the lending market."

Today, many area residents continue to advise and work with city officials, schools, and businesses to encourage diversity and inclusion through education, policy, employment, and fair housing efforts. The Black community’s story in Appleton is one of resistance and resilience in the face of racist discrimination.