Article 9

Driving While Black

Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections

Have you ever felt unsafe while traveling?

When you need a safe place to stop, what do you look for?

Have you ever been on a road trip?

More Americans traveled in the mid-twentieth century than ever before. New interstate highways, less expensive cars and fuel, and higher disposable incomes made it possible for many more people to hit the road for business and pleasure. Most people understood the segregated boundaries of their own hometowns. But what about when they traveled?

Obry Wendall "Winks" and Ruth Hamlet built Winks Lodge in 1925 in Lincoln Hills Country Club, the only resort designed for Black travelers at the time. Black artists like Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, among others stayed there after performing in Denver.

Courtesy of Lincoln Hill Cares

For travelers of color, danger was always just around the corner. Choosing the wrong place to stop for a meal, a night’s stay, or a public restroom could lead to anything from humiliating confrontation to a physical attack. Some families learned to travel with a stash of ready-to-eat food, blankets and pillows for sleeping in the car, gas cans, and portable toilets – just in case.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) owned the Fantastic Caverns from 1924 to 1930. During this time, they held meetings inside the cave.

Courtesy of Missouri State University

U.S. Route 66, completed in 1936, was one of the first highways to connect the nation. It ran through 44 all-White counties—almost half of the 89 counties between Chicago and Los Angeles. Black travelers learned to recognize signs of danger. A business that included three “Ks” in its name (such as “Kozy Kamp Kottages”) or advertised “all-American” cuisine was often code for businesses run by a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) member. Klansmen even ran roadside tourist attractions. During the 1920s, the Missouri KKK owned Fantastic Caverns, a drive-thru cave. They used the cave’s Grand Ballroom for ceremonies and cross burnings.

Resource

Candacy Taylor discusses the experiences of Black motorists on Route 66 and the Negro Motorist Green Book.

Jewish travelers often had trouble finding hotels that would rent them rooms.

The Borscht Belt welcomed and attracted upper-middle-class Jewish families from the New York City area. Jews were often not welcome at resorts and country clubs.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Jewish travelers often had trouble finding hotels that would rent them rooms. Starting in the 1920s, the Borscht BeltBorscht Belt: A popular location for Jewish tourists from New York City from the 1920s to the 1960s. Responding to other hotels refusal to serve Jewish clientele, these resorts in the Catskills (particularly Sullivan, Orange, and Ulster counties in upstate New York) were prime vacation destinations. At its height, approximately 500 hotels, bungalow communities, and summer camps catered to 150,000 visitors a year. in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York was advertised as a welcoming place for American Jews to vacation. Travelers’ information in Jewish newspapers listed restaurants, hotels, and resorts that hosted up to one million Jewish travelers a year by the 1950s. Those culturally specific travel guides set an example adopted by others.

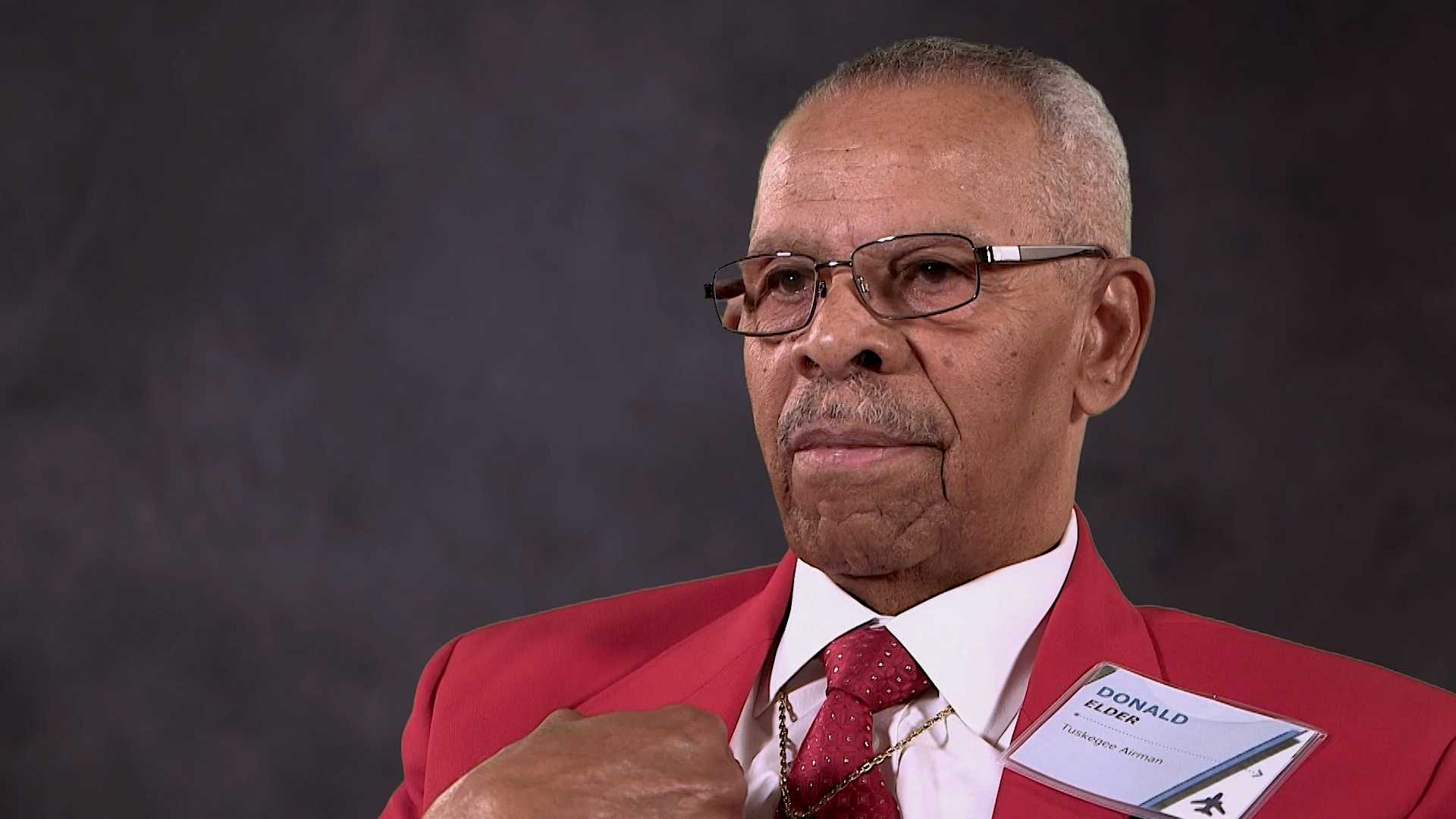

I told him I had a reservation. And I remember him saying, ‘I don't care what you have. You can't stay here.’

Tuskegee Airman

ViewHide Transcript

While I was there, Grumman decided to send a person, no, it was Northrop, well Northrop Grumman, to send a person to Albuquerque on an airplane they had out there, and the long and short of it is he ended up leasing my house from me because I went back to Columbus.

Well, matter of fact, North American sent Tom Johnson out there to join me after a while. You see, those times again I can always remember, like driving from Columbus. I stayed at the Holiday Inn in St. Louis, Missouri. But when I left St. Louis driving further, they had made a reservation for me in Oklahoma City. When I got to Oklahoma City and I went to the counter at the Holiday Inn. The guy looked at me really startled, and I told him I had a reservation. And I remember him saying, “I don't care what you have. You can't stay here.” Oh, okay. I couldn't stay. So I stayed some little fly-by-night somewhere, and I left Oklahoma City. When I got to Albuquerque, that's when Wizner met me and he made certain that I got into a nice hotel, motel on Central Avenue in Albuquerque. I had that kind of an experience, but that was in 1950, 1960.

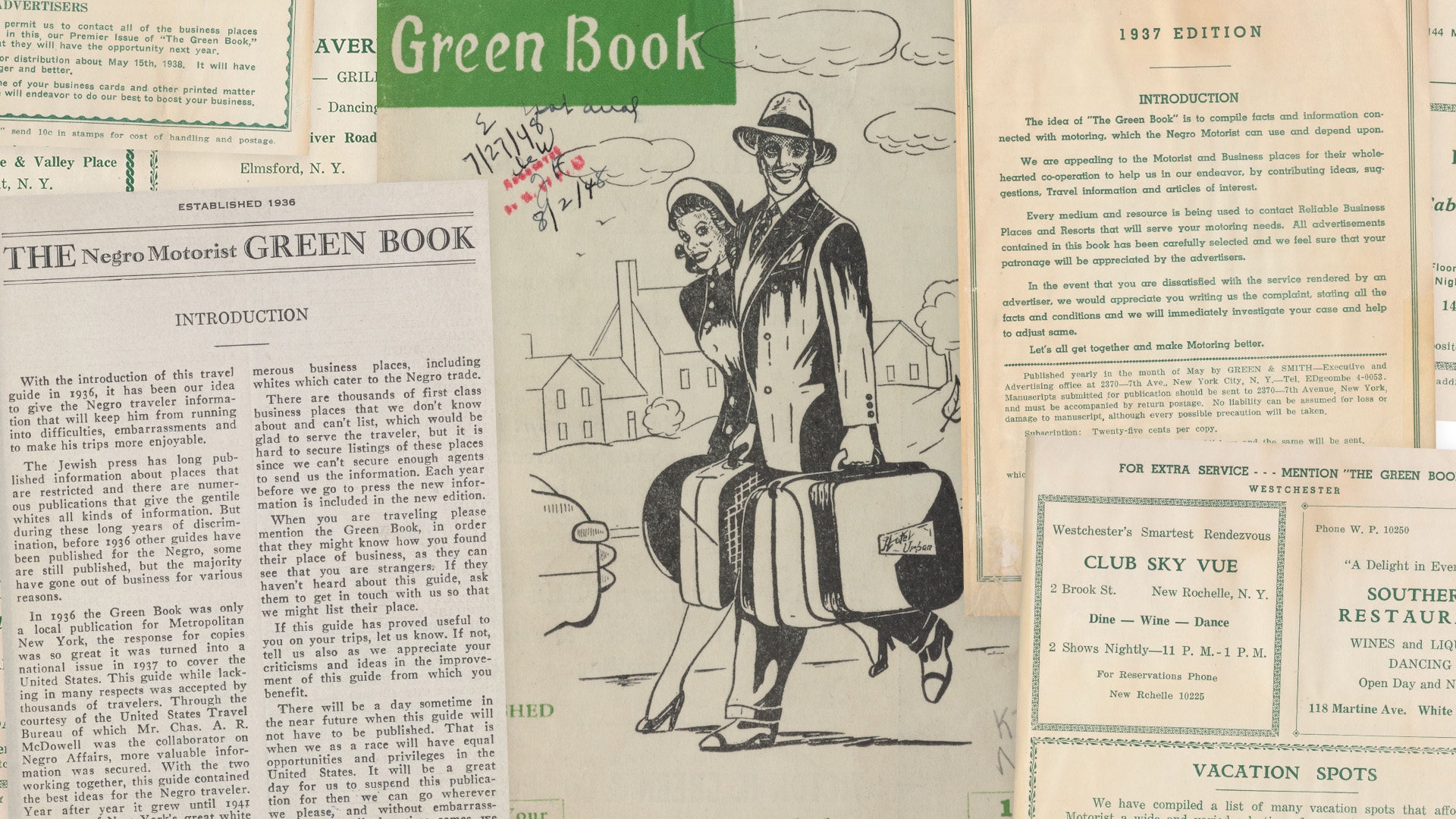

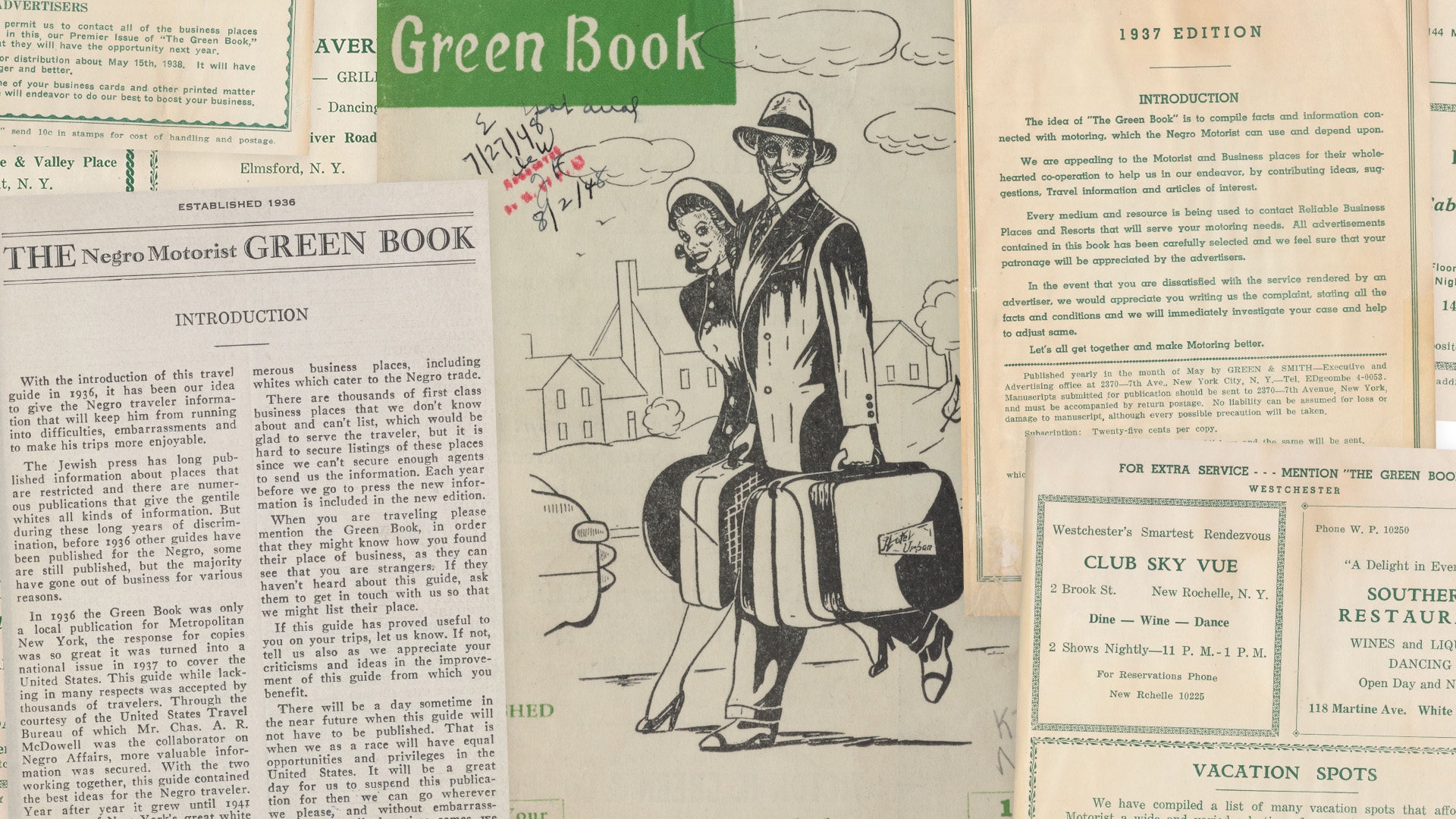

The Negro Motorist Green Book provided recommendations for Black American travelers seeking lodging, dining, and other services while vacationing in the United States.

Courtesy of the The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Victor H. Green, a postal worker from Harlem, launched a popular Black travel guide in 1936. The Negro Motorist Green Book stayed in print until 1966. The Green Book and similar guides listed Black-owned restaurants, hotels, barber shops, gas stations, attractions and even the homes of local Black residents willing to rent rooms. By 1962, two million Green Books were circulating each year, thanks in part to a deal with Esso Gas Stations (known as Exxon Mobil today). People of color supported one another by starting businesses that served tourists. Rooming houses in vacation spots, like Shearer Cottage on Martha’s Vineyard, Rock Rest in Kittery, Maine, or the Oakmere Hotel in Idlewild, Michigan, sprang up to offer Black travelers a tourist experience in a segregated land.

Resource

The New York Public Library has digital versions of Victor Green's travel guides to explore.

Additional Resources

Candacy Taylor discusses the experiences of Black motorists on Route 66 and the Negro Motorist Green Book.

The New York Public Library has digital versions of Victor Green's travel guides to explore.