Local Spotlight

Columbus, Ohio

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

Community Profile

- Community: Columbus, 1797

- County: Franklin, Delaware, and Fairfield

- State: OH

- Type: Urban

- Metro: Columbus

Ohio was the ancestral homelands of the Shawnee, Seneca-Cayuga, Lenape, Wyandot, Ottawa, and Myammia. The first non-Indigenous settlement in Central Ohio, Franklinton, was erected in 1797 by surveyor Lucas Sullivant, among others. This area became Columbus, which would later become the capital city of the state. The 1810 US Census counted 43 Black Americans in the new Franklin County. The Black American population grew steadily until the early 1900s, when the population increased dramatically due to the large migration of Black Americans from the South into northern urban areas. Many historic Black communities in Columbus established their early roots during this time, including the Near East Side. This community’s Black American historical tapestry includes threads of the Great Migration, community activism, art and music, and family history. Today, Columbus is home to over 905,000 people, including a Black American population of 264,000.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 53.4%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $175,000

- Median Gross Rent: $974

- Median Income: $61,305

- Poverty Level: 15.7%

- High School (ages 25+): 91.2%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 40%

A Place to Call Home — The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of Poindexter Village

Poindexter Village, a crowd gathers to see the finished housing and if it indeed had the amenities promised in its promotion.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

Reita Smith grew up in Poindexter Village, a public housingPublic Housing: The Housing Act of 1937 provided subsidies for local authorities to build affordable, safe housing for low-income families and seniors, known as public housing. Currently, there are 3,300 public housing authorities in the United States that house around 1.2 million residents. development in Columbus, OH. She remembers living there with such joy and fondness that she recently fought to have the complex preserved on the National Register of Historic Places. Poindexter Village, one of the first public housing complexes for Black residents, is integral to Columbus’ fair housing story.

A decade of effort by the community, including former residents, preservationists, historians, activists (including Reita Smith) and other partners working together resulted in a museum and cultural center.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

Throughout the nineteenth century, many Black enclaves developed in the Columbus area. The promise of economic opportunities and freedom from racial violence and terror led millions of Black Americans to move from the rural South to the urban North. From the years after the Civil War through the peak of the Great Migration,Great Migration: Approximately six million Black people migrated from the southern states to the northern, midwestern, and western states from 1910 to 1970 to escape violence and threats of violence prompted by living under Jim Crow. Better working and educational opportunities were sought primarily around the larger urban areas of the country with the most significant migrations happening between World War I and World War II. Despite seeking better opportunities elsewhere, the Great Migration prompted demographic changes that incited increased racial discrimination and continuing racial inequity.

thousands of Black citizens arrived in Columbus. Many quickly learned that opportunities for Black people in the North were also limited, and it took time to establish thriving communities. By the 1940s, Columbus’ Near East Side was a popular migrant destination and a flourishing hub for Black businesses, churches, social organizations, and other community institutions.

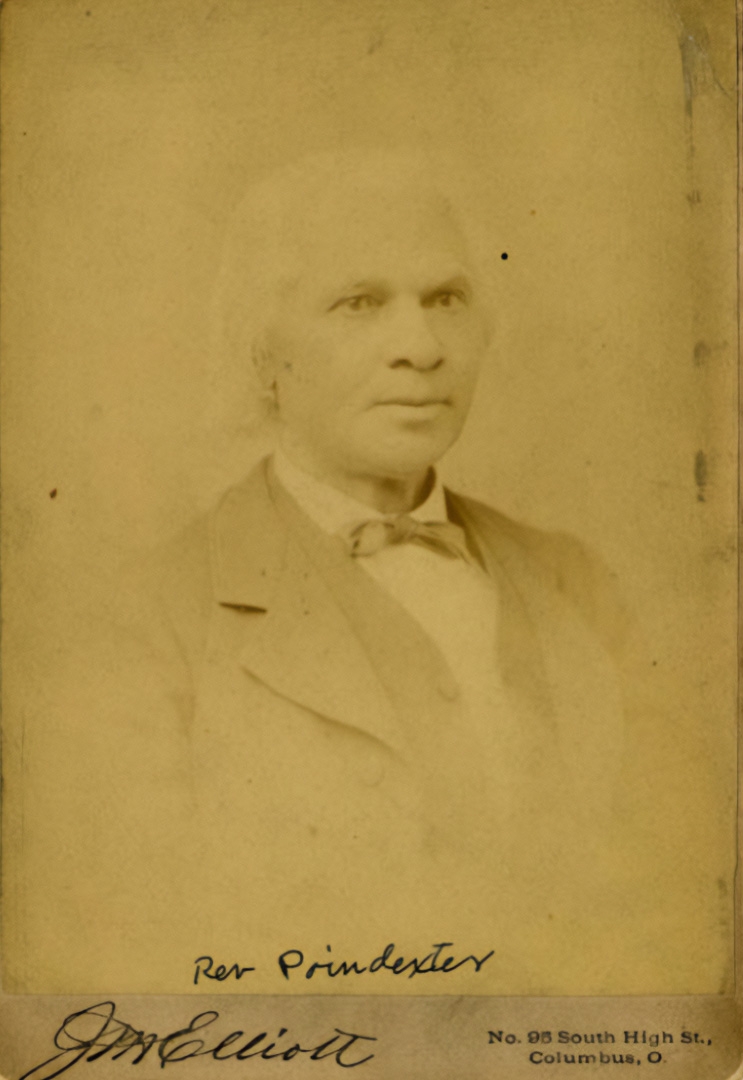

Carte de visite portrait of Reverend James Poindexter (1819-1907) of the Second Baptist Church in Columbus, Ohio.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

As Columbus’ Black population increased, White residents employed discriminatory devices and practices of segregation such as restrictive covenants,Restrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group. violence, and the threat of violence to severely limit the settlement of Black newcomers. Though Ohio’s Civil Rights Law of 1884 banned racial segregation and discrimination in public facilities, it was weakly enforced. White businesses openly disregarded the law by posting “Whites Only” signs in their windows and refusing to hire or serve Black residents. Civic associations lobbied to block construction of Black housing near traditionally White neighborhoods. Schools were segregated by gerrymanderingGerrymandering: Manipulating the borders of electoral districts to favor one political party or interest over another.

student attendance zones that divided neighborhoods by race. When Black families attempted to move into White neighborhoods, they were met with intimidation.

In the early twentieth century, increased racial segregation coupled with the expanding Black population caused overcrowding and deteriorating living conditions in Columbus’ constricted Black neighborhoods. On the city’s Near East Side, this lack of housing choice contributed to the emergence of the Blackberry Patch, a neighborhood of substandard housing and sanitation. Like many places in the country during the 1920s, White residents in Columbus founded a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) grounded in white supremacy. For two years, the pro-Klan film Birth of a Nation played twice a day at the Hartman Theater. However, Black community life thrived in Columbus despite the intense discrimination and segregation.

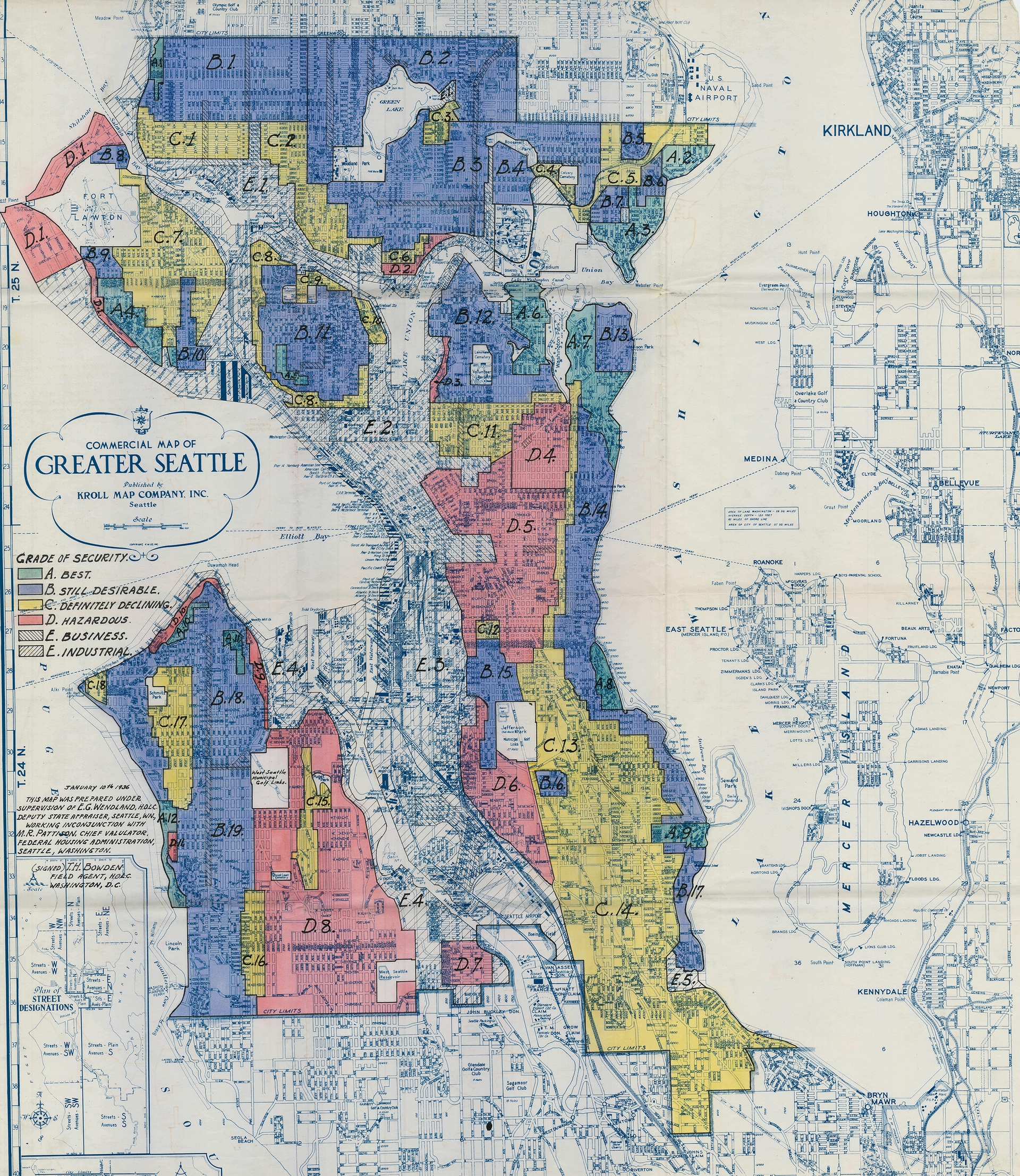

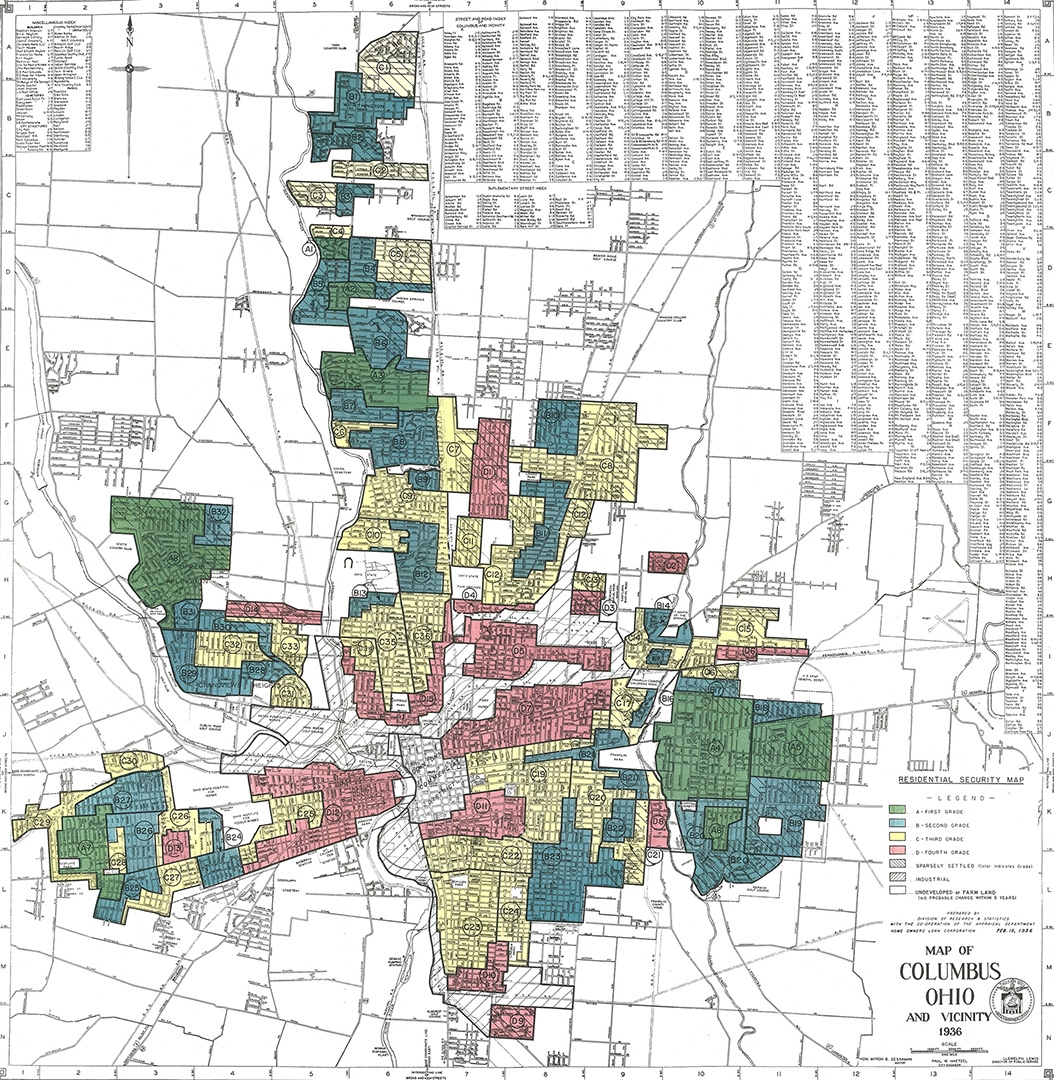

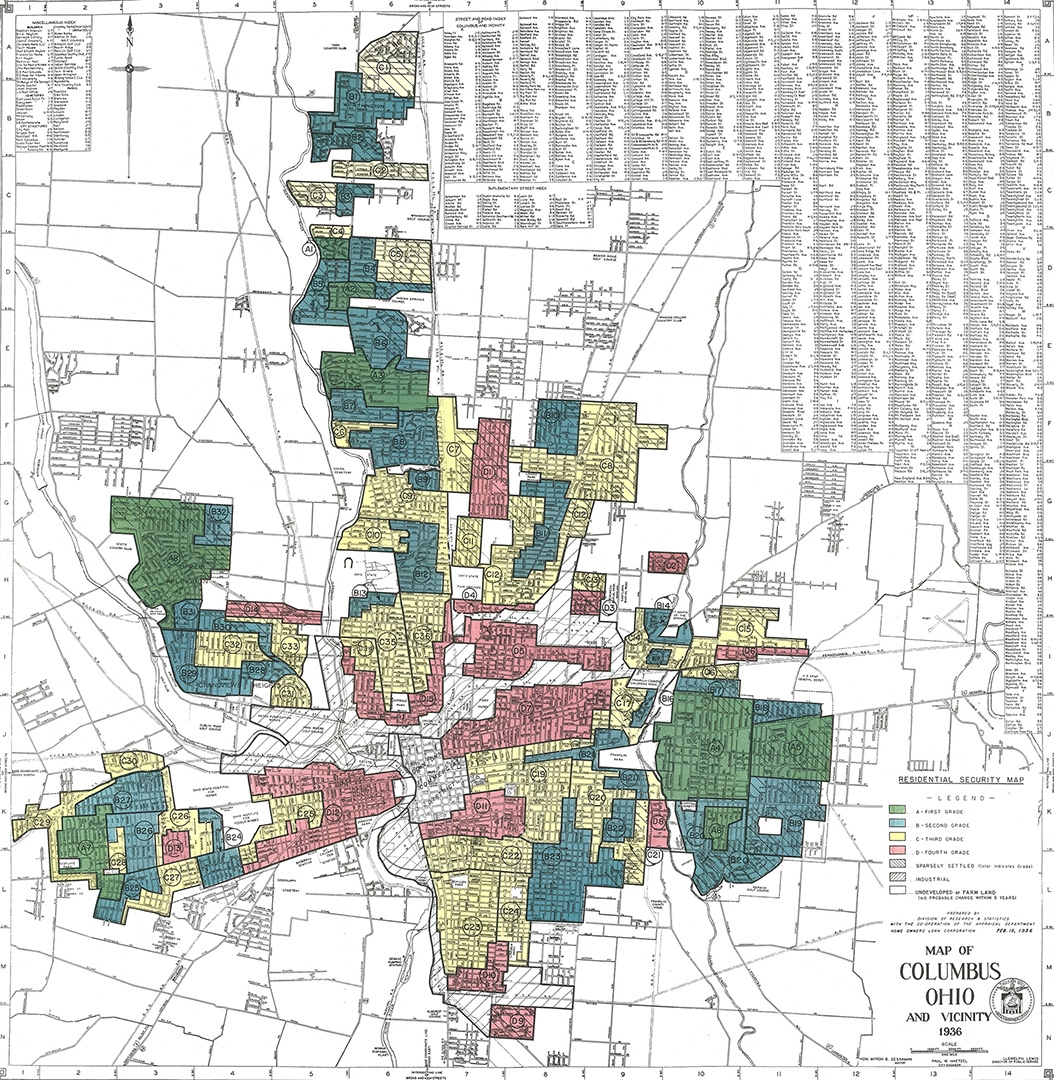

Redlining Map of Columbus, Ohio.

Courtesy of the National Archives

In 1937, the Federal Housing Act provided federal funds for the construction of affordable public housing for Americans suffering from the impacts of the Great Depression. This legislation explicitly stated that public housing developments must reflect the racial composition of the neighborhoods where they were to be built. Over the next decades, housing projects were disproportionately built in White neighborhoods, leaving people of color with limited access to affordable public housing. Only a fraction of funding went to segregated housing for Blacks.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt greeting the Columbus community at the October 12, 1940 opening of Poindexter Village. Community members have fond memories of the First Lady's dedication to the project.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

In 1940, the Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority completed the construction of Poindexter Village, the city’s first affordable public housing project and one of the earliest in the nation. The 400-unit low-rise apartment complex was built exclusively for Columbus’ Black population. Though many inhabitants of the Blackberry Patch moved into Poindexter Village, there was not room for all. The Blackberry Patch was razed in the 1930s and racial segregation and redliningRedlining: Redlining is the practice of denying mortgage loans to people living in neighborhoods determined to be financially risky. The name comes from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which during the New Deal commissioned maps that color coded neighborhoods from Green (Best), Blue (Still Desirable), Yellow (Declining), and Red (Hazardous). It was virtually impossible to get a loan in a red area and almost every Black neighborhood was denoted as red. left fewer than 100 units of replacement housing available to its former residents throughout the city. Those who moved into these units faced higher rents and overcrowding.

Unlike White public housing developments, which skewed toward a lower-income demographic, Poindexter Village’s residents were socioeconomically diverse. Though many middle-class Black residents could afford homes in other neighborhoods, they were barred by racial restrictions from renting or purchasing those homes. Early residents of Poindexter Village formed a diverse community of doctors, professors, and lawyers mixed with factory workers, domestic servants, chauffeurs, and merchants. Poindexter Village offered its residents a place to call home.

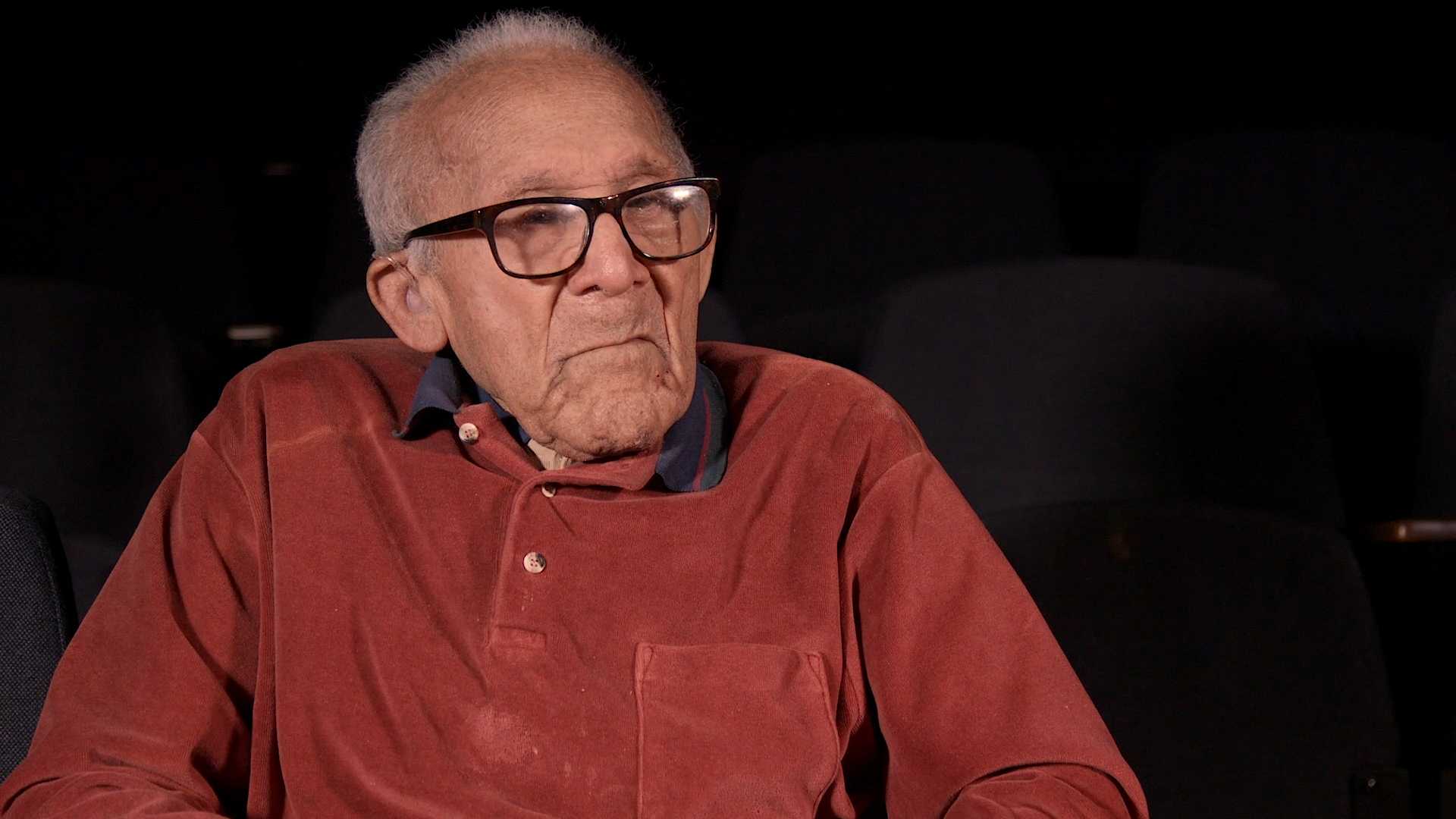

She knew what was going on in the neighborhoods and all over the country.

Former Poindexter Resident

ViewHide Transcript

After the first Poindexter village was built, they had a parade for him in an open sedan here in Columbus. And I was as close to him almost when he passed by, as I am to you. And the car stopped and I got, you know, I looked at him just like I'm looking at you right now. He was in an open sedan. It was a great day. Every colored person. That could line the street, lined the street. When he went around because it wasn't so much Roosevelt, it was Eleanor Roosevelt that influenced him. Eleanor Roosevelt was one great woman. No doubt about it. She would travel around and she got hear, talk to the people and she knew what was going on in the neighborhoods and all over the country. She traveled all over the country.

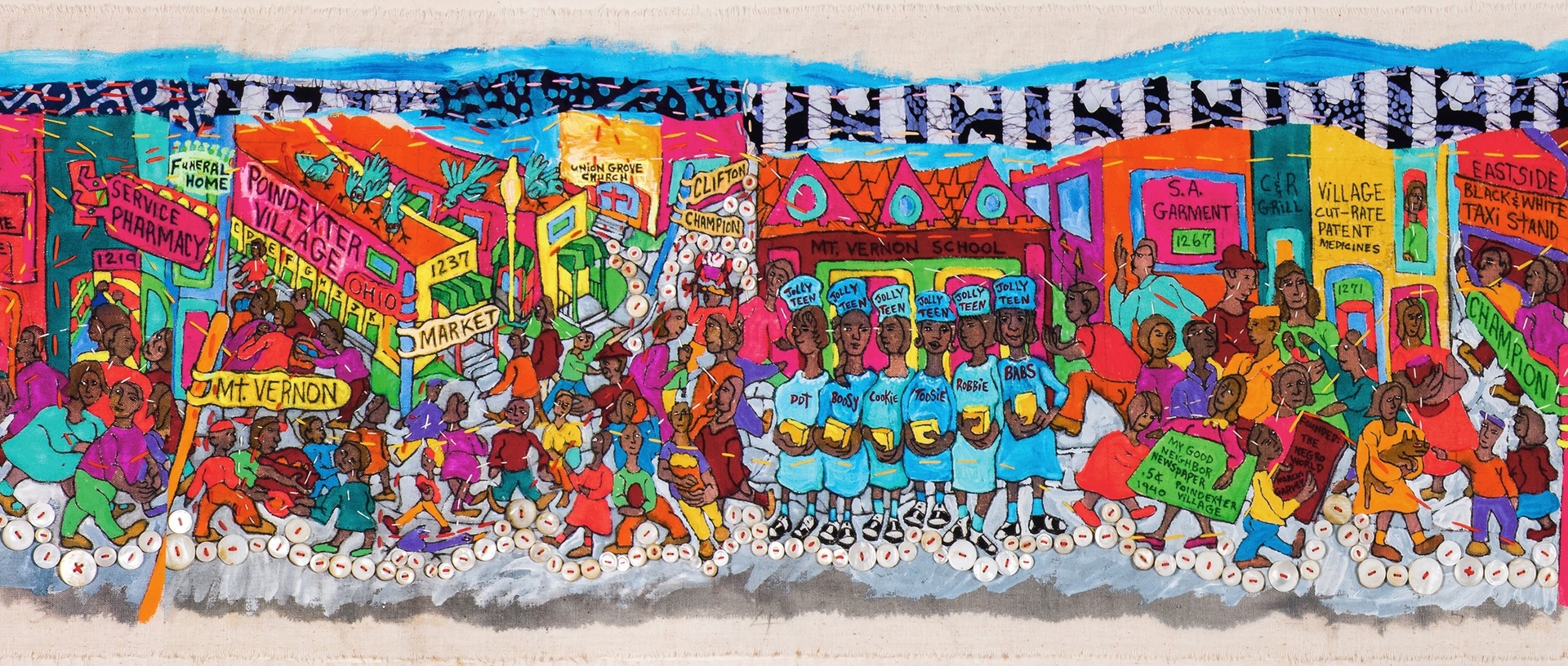

It provided a sense of community and dignified housing they had been previously denied. The units featured steam heat, gas stoves, and other amenities that were not available in the Blackberry Patch. Residents of Poindexter Village supported an adjacent flourishing business district of Black-owned companies and cultural institutions. Residents took pride in Poindexter Village, and it became the center of Black activism, culture, and community life in Columbus. Poindexter Village thrived through the 1960s. The community nurtured its residents, producing many successful individuals. One notable resident was Amina Brenda Lynn Robinson, a world-renowned artist. Robinson, in her colorful mixed-media work, brought to life the vibrancy of the Poindexter Village community.

Poindexter Village offered its residents a place to call home.

Mixed-media artist Aminah Robinson’s work A Street Called Home is her tribute to the community of Poindexter Village. Robinson used old city directories and photos the capture all the businesses on the street.

Courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio Museum Purchase with funds donated by Wolfe Associates, Inc.

Dated May 13, 1940, photograph of two men carrying a bed frame into one of the units at Poindexter Village in Columbus, Ohio.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

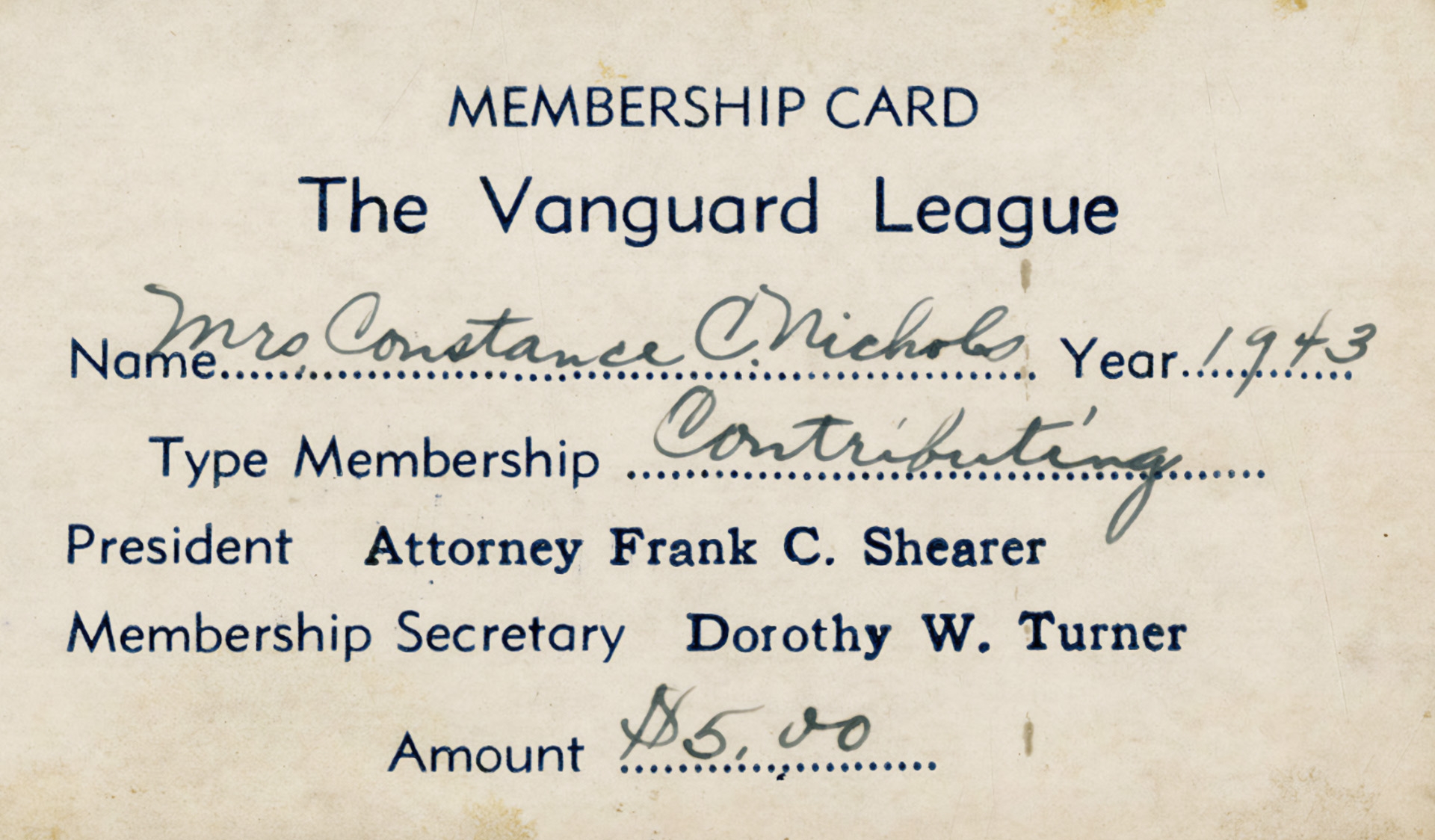

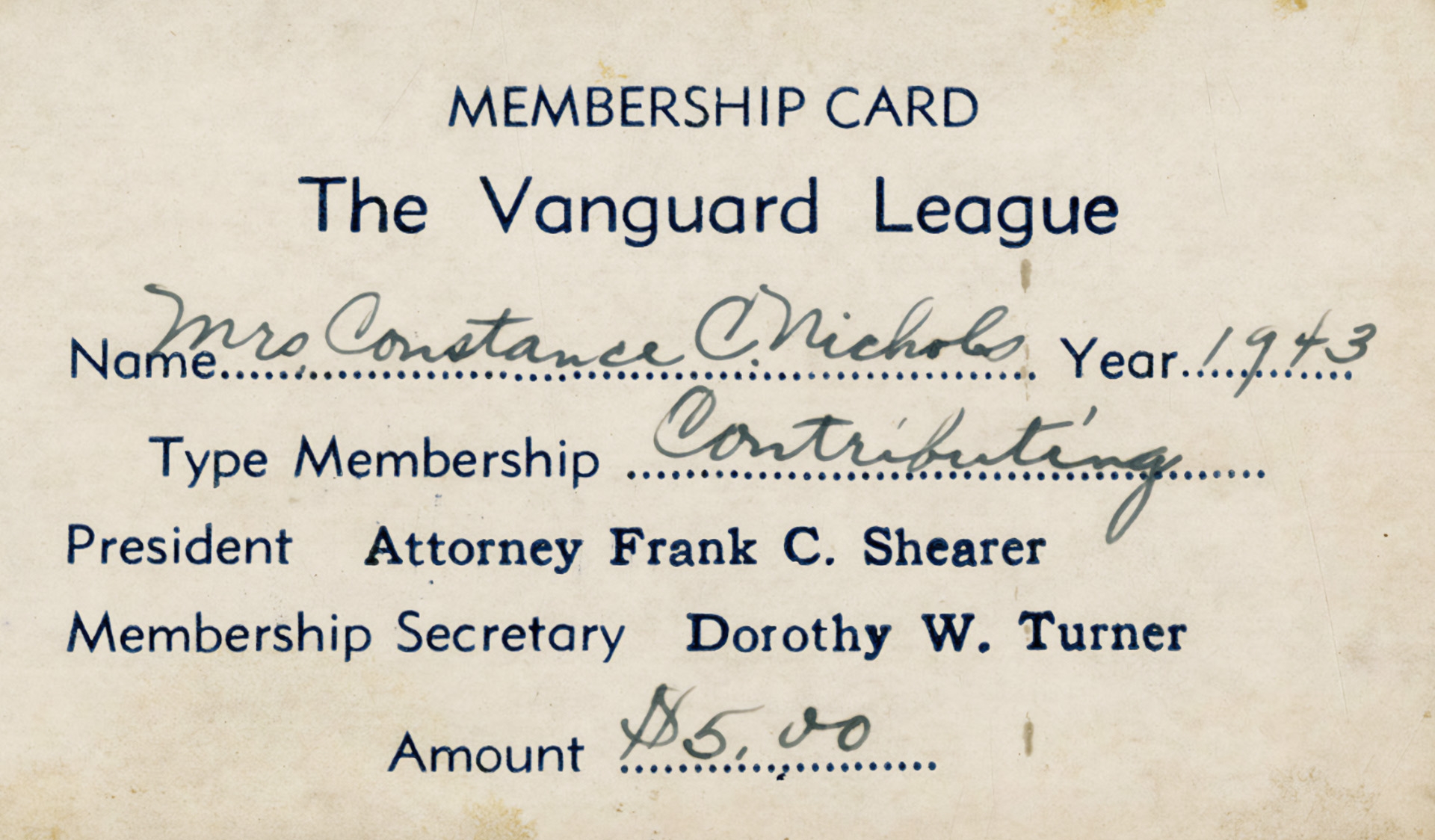

Even before the mid-twentieth century civil rights movement, Columbus’ Vanguard League led efforts for change. The League began meeting in the home of Mrs. Constance C. Nichols in 1940 to discuss possible solutions to racial discrimination. League members sought to use nonviolence to address discrimination in hiring, housing, schools, and community conduct, uniting under the motto “For equality, opportunity, liberty, and democracy for Negroes.” Using lawsuits, picketing, and other methods, they achieved significant success. Their campaigns were able to secure positions for Black women at the Curtiss Wright aeronautical plant, and they successfully desegregated many theaters in Columbus. However, the group’s efforts to desegregate schools were unsuccessful. By the 1950s, membership waned as more civil rights organizations formed on the East Side. The League joined the Columbus chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), whose mission was to “bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background.”

Membership card for Mrs. Constance C. Nichols in the Vanguard League for the year 1943.The Vanguard League was dedicated to civil rights in the Columbus, OH area. As a contributing member her annual dues were $5.00. Nichols was a founding member of the League, which formed during a meeting at her home in 1940.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

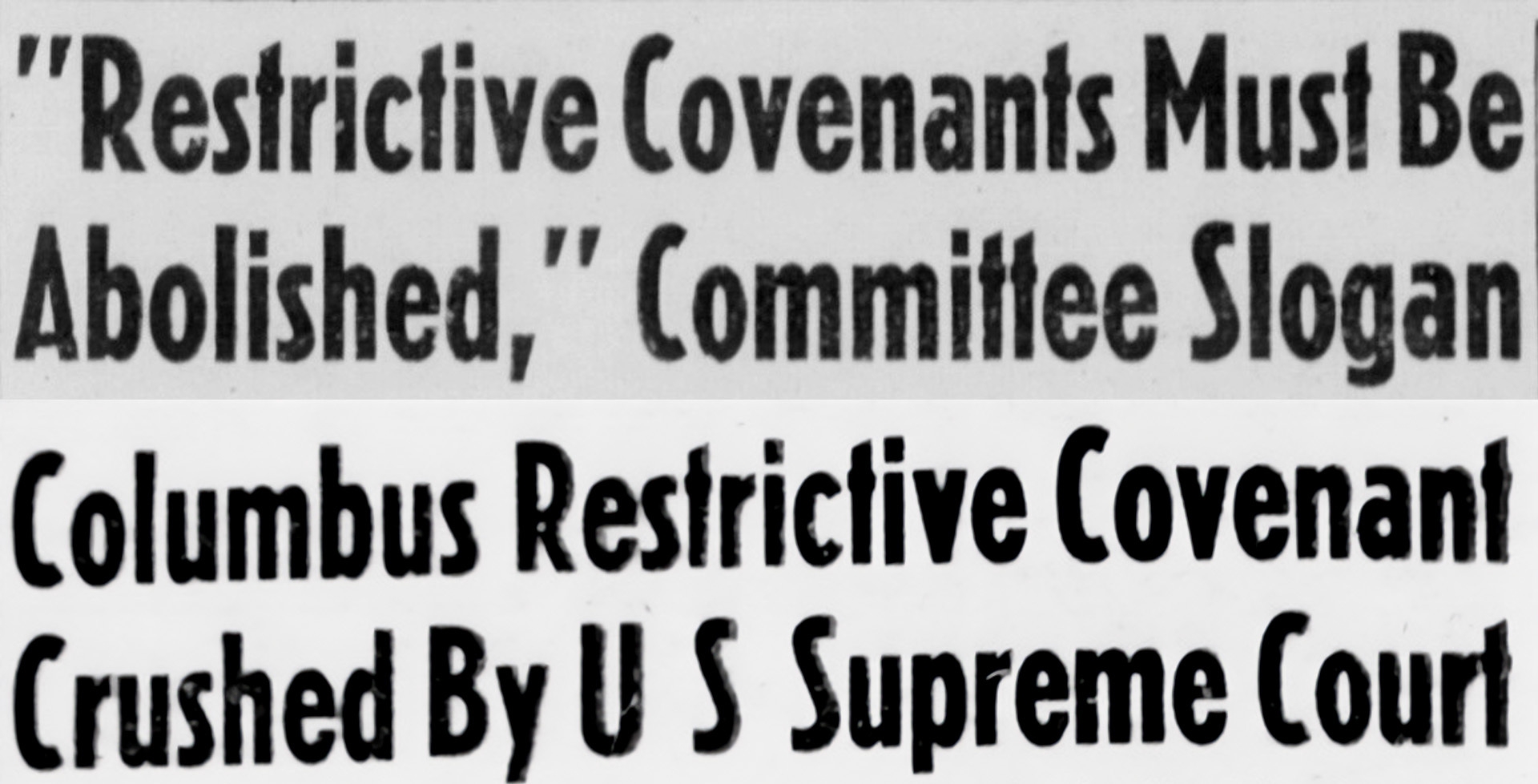

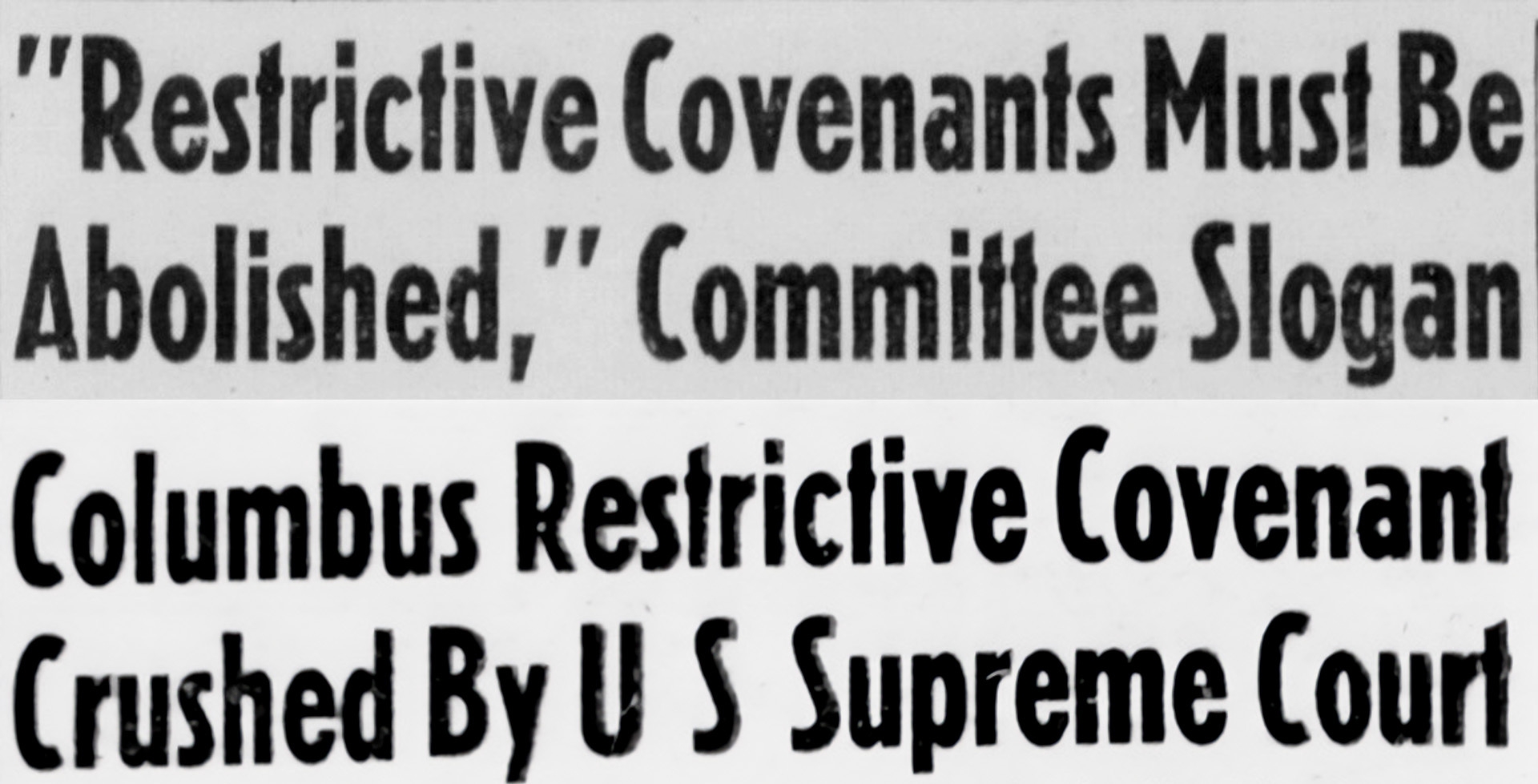

In 1947, the Ohio Supreme Court refused to hear a case about restrictive covenants, deeming “the question of the covenant was not one of great public interest.” In contrast, journalist Wilhelmina Jones, writing for the Black newspaper the Ohio Sentinel, found the public interested in her coverage about the unfairness of restrictive covenants and the shortage of housing for Black residents.

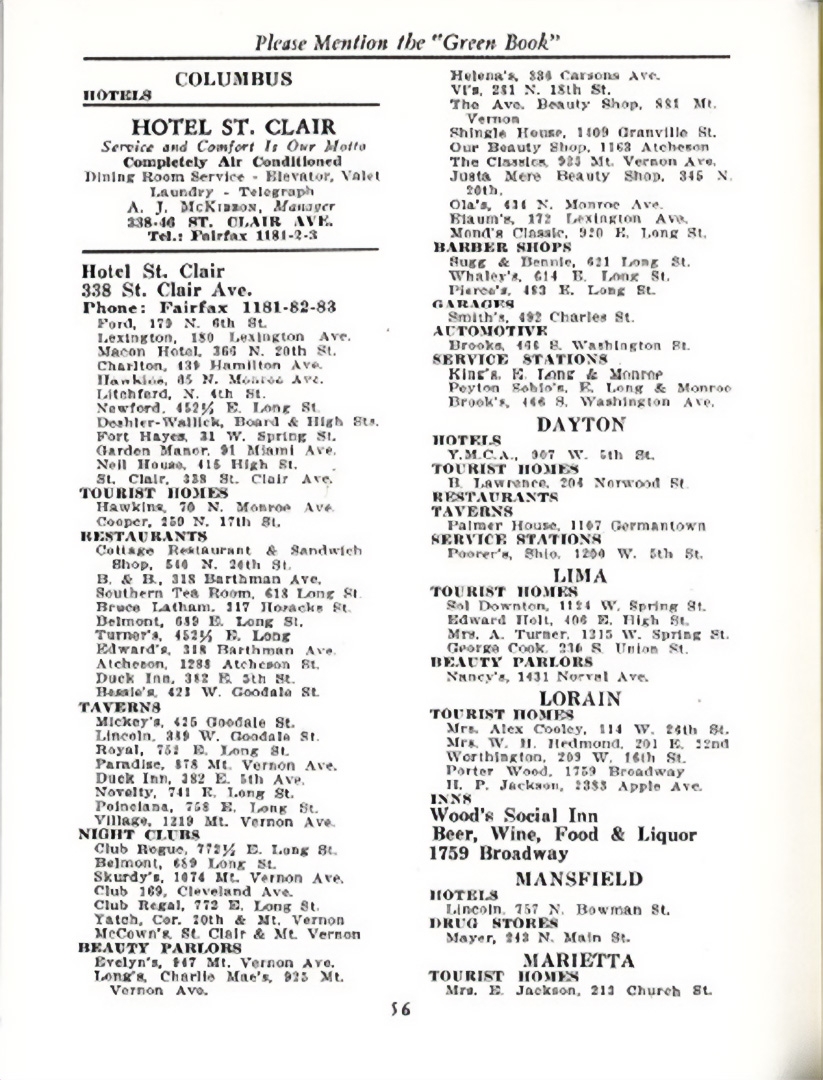

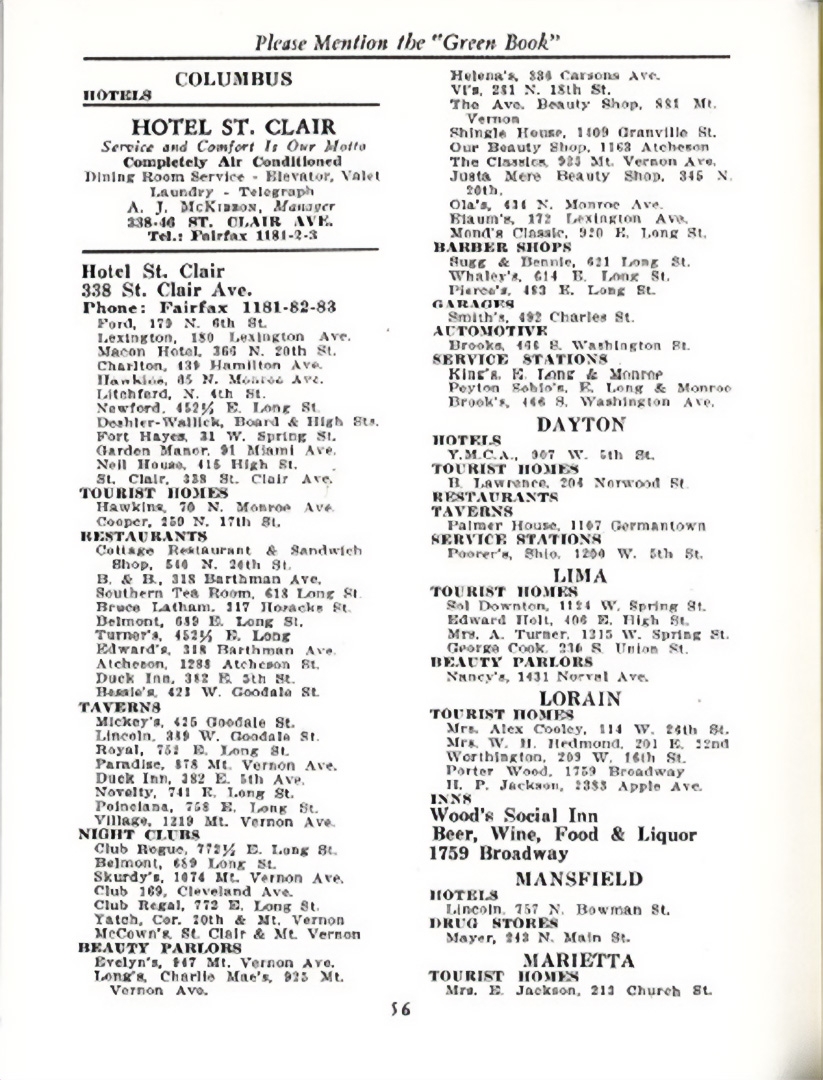

Published by Victor H. Green annually from 1936 to 1966, The Negro Motorist Green Book served as a guidebook for Black people traveling in the United States during a time of racial prejudice, violence, and unfair treatment. These pages are from the Columbus edition of the 1953-1954 Green Book.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

Even as Columbus’ civil rights leaders organized, Poindexter Village deteriorated. Similar trends were impacting Black public housing throughout the country. In 1952, six Black couples purchased abandoned farmland east of Poindexter and created the Livingston Heights Place subdivision. Ten years later, two couples purchased vacant land to the northeast, creating Teakwood Heights, a Black subdivision of 13 homes that eventually expanded to 77 houses. These sold by word of mouth to professionals and upper-middle-class Black families, though some had to go as far as New York to secure financing. A racially-mixed East Side suburb, Berwick, also developed. In the late 1960s, fair housing acts and ordinances eased some restrictions on housing for middle-class Black families, spurring them to buy houses in previously restricted areas.

The Columbus Black community resisted and fought against racial restrictions like restrictive covenants through court cases and major organizations such as the NAACP, the Vanguard League, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, and especially the Black Press.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

The exodus of these residents from public housing left more financially vulnerable people behind, with their choices still limited by redlining and neighborhood isolation caused by highway construction. Public investment in affordable housing declined, resulting in a cut to services and maintenance in older public housing units. Many vacant units, too costly to repair, were boarded up. Due to this disinvestmentDisinvestment: The act of withdrawing financial support or investment., public officials called for the demolition and redevelopment of Poindexter Village. A coalition of former residents and preservationists fought to protect and restore the buildings, but of the 37 buildings that once made up this thriving community, only two were saved. With new construction neighboring these older sites, Poindexter Village is now beginning a new chapter. Once restored, the two remaining buildings will house a museum and learning center. This historic site will share the story of a thriving early-twentieth century Black American community and the legacy of the Great Migration in Columbus.