Article 5

Discriminatory Zoning

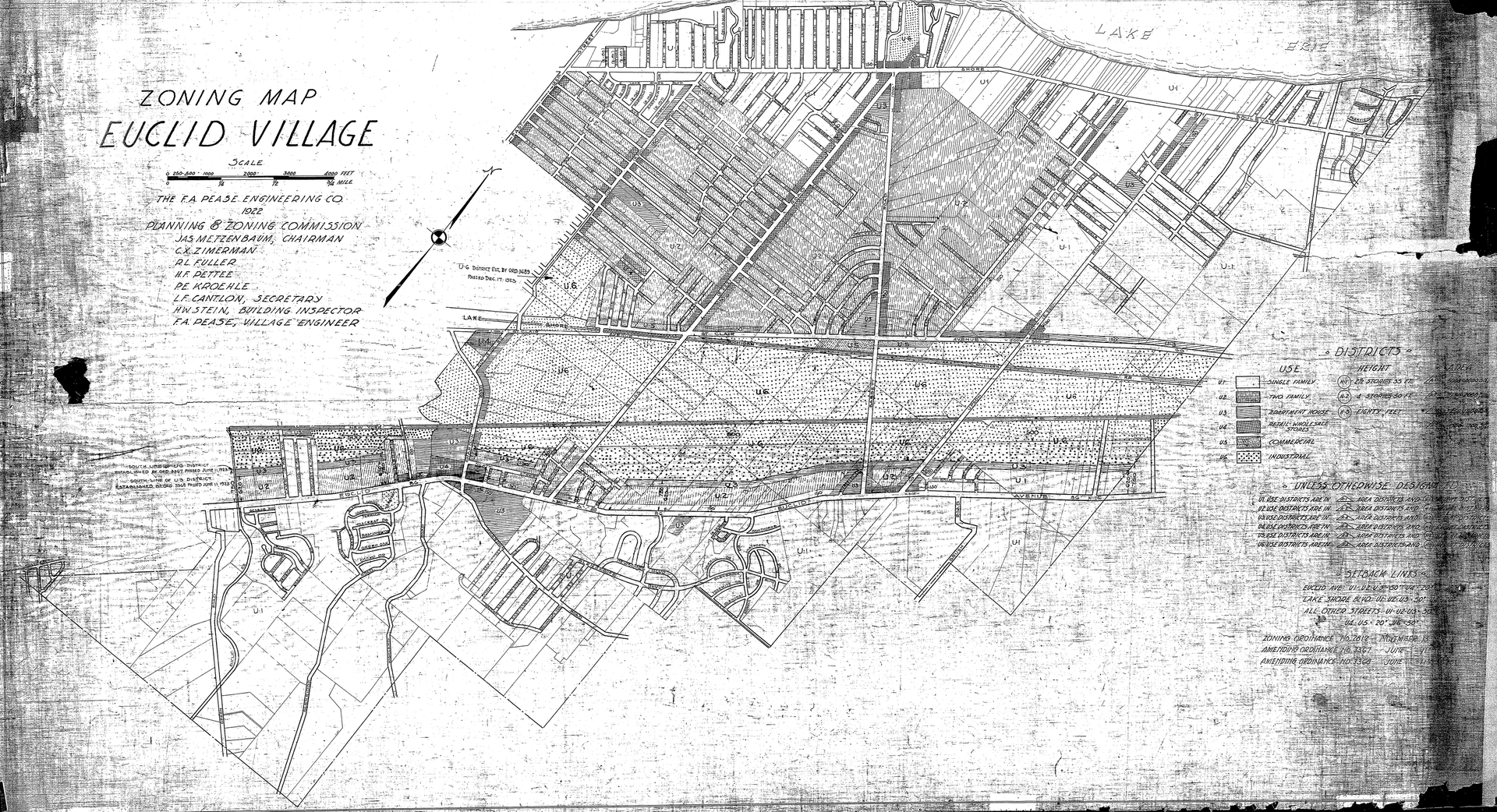

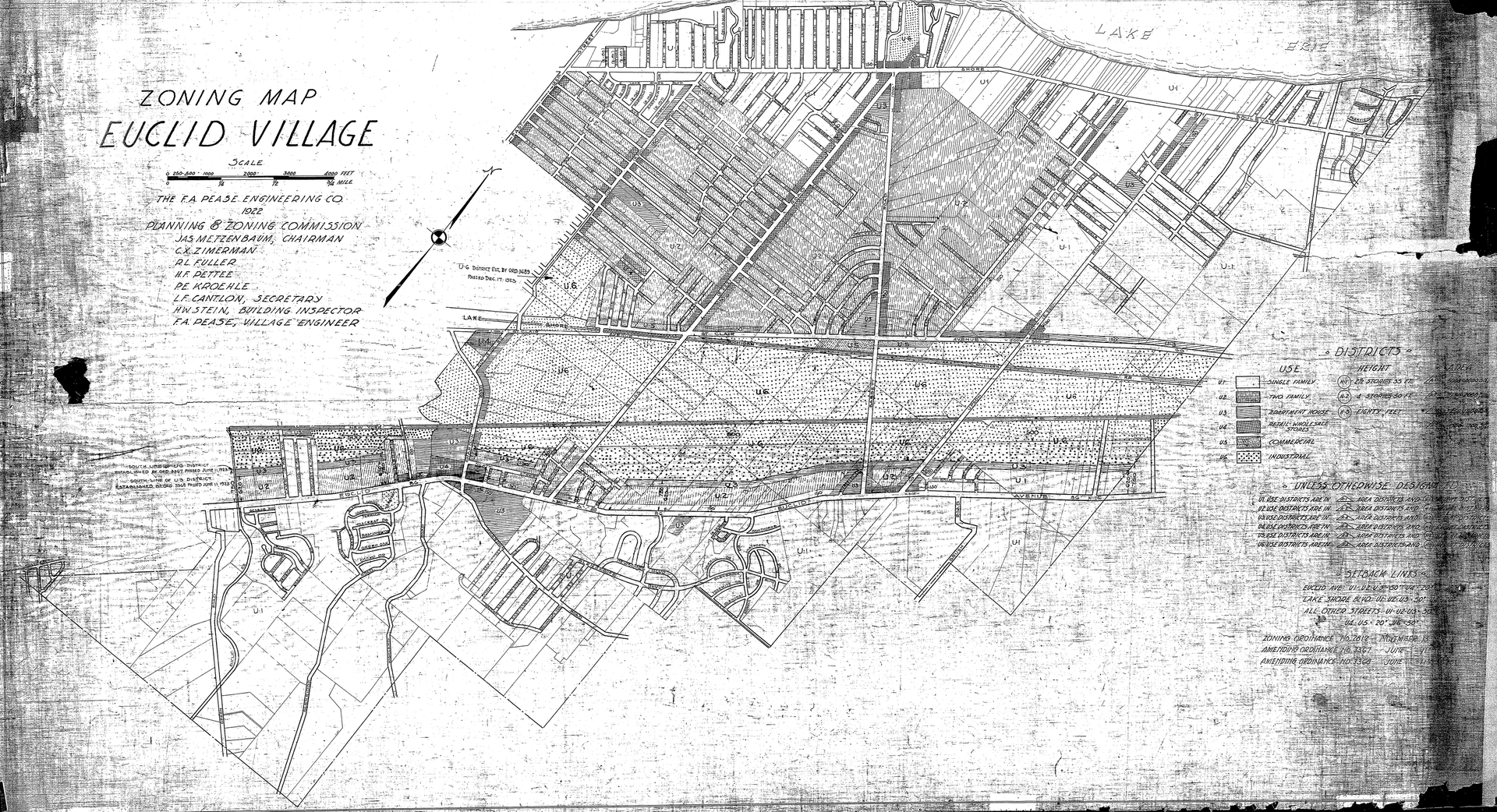

Courtesy of the City of Euclid, Ohio

Discriminatory Zoning

ViewHide Transcript

Over the last century, residential segregation was enforced through two key tools: public zoning laws and private restrictive covenants.

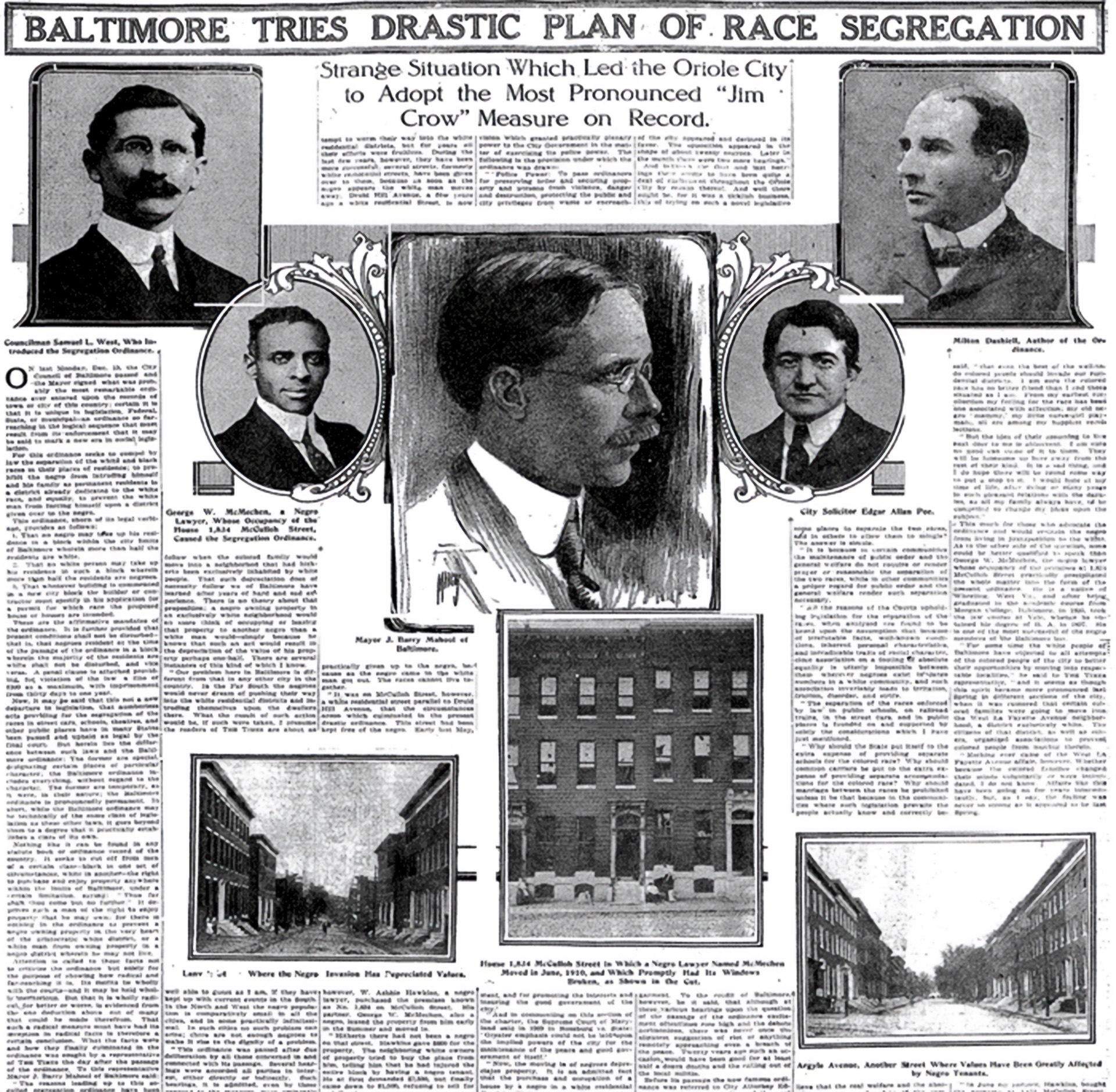

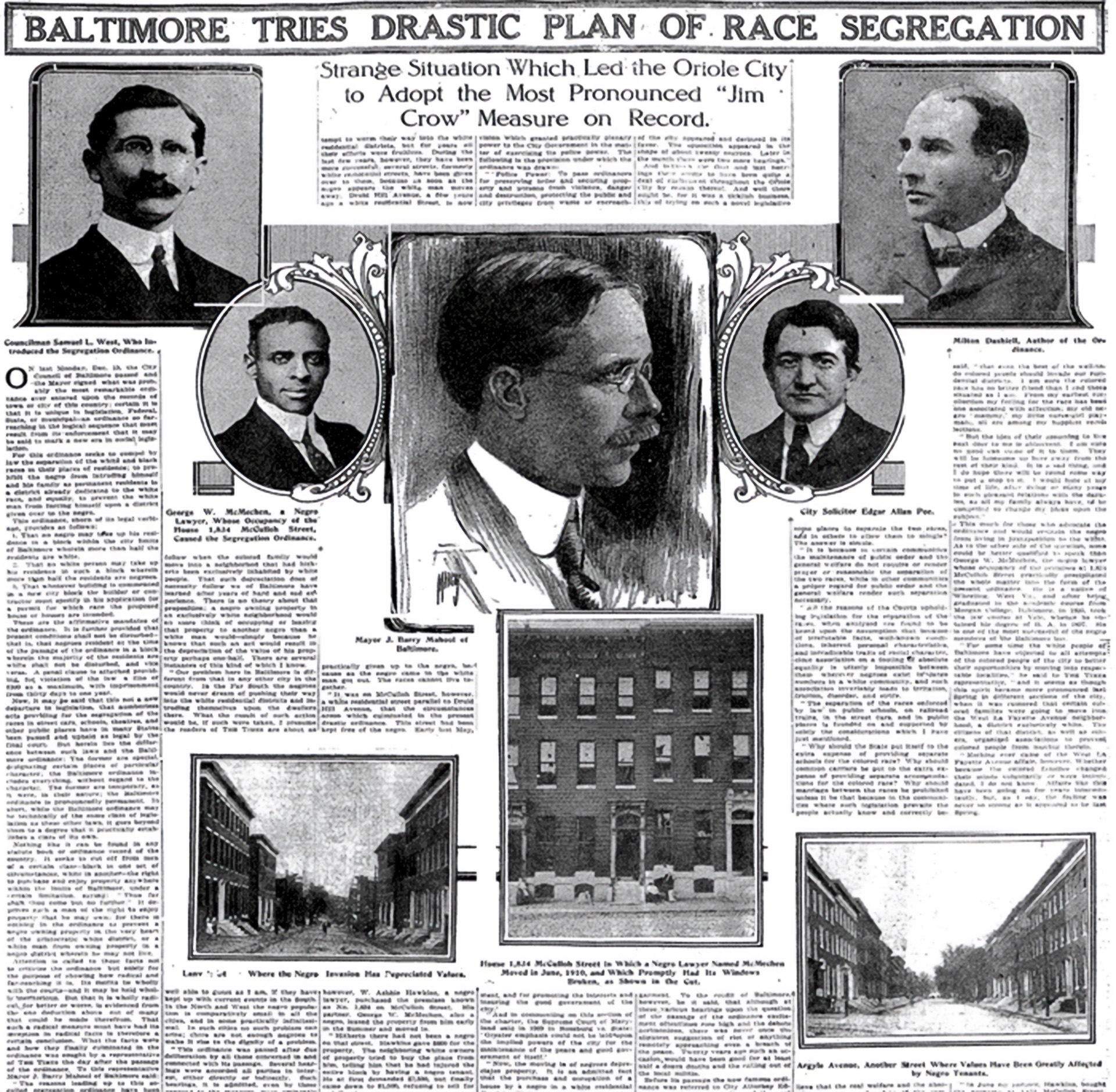

In 1910, the first zoning ordinance was created in Baltimore after a Black attorney bought a house in a prestigious White neighborhood.

In response, the city passed a law to stop Black people from moving into majority White blocks, and vice versa. Anyone who did faced a hefty fine and a year in jail.

The Baltimore ordinance was too vague to stand up in the courts, but the idea behind it took off. Within a few years, Louisville, Kentucky had its own zoning ordinance. It was an attempt to curb rising Black property ownership in the city.

The NAACP prepared a legal challenge, and in 1917, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In Buchanan v. Warley, the Court struck down racial zoning. They recognized it as a violation of the 14th Amendment and the practice became illegal.

But this didn’t stop cities from passing zoning laws. Zoning was often used for the public good, but it was also used as a tool for discrimination. Within twenty years, more than 1,000 American cities had zoning ordinances on the books.

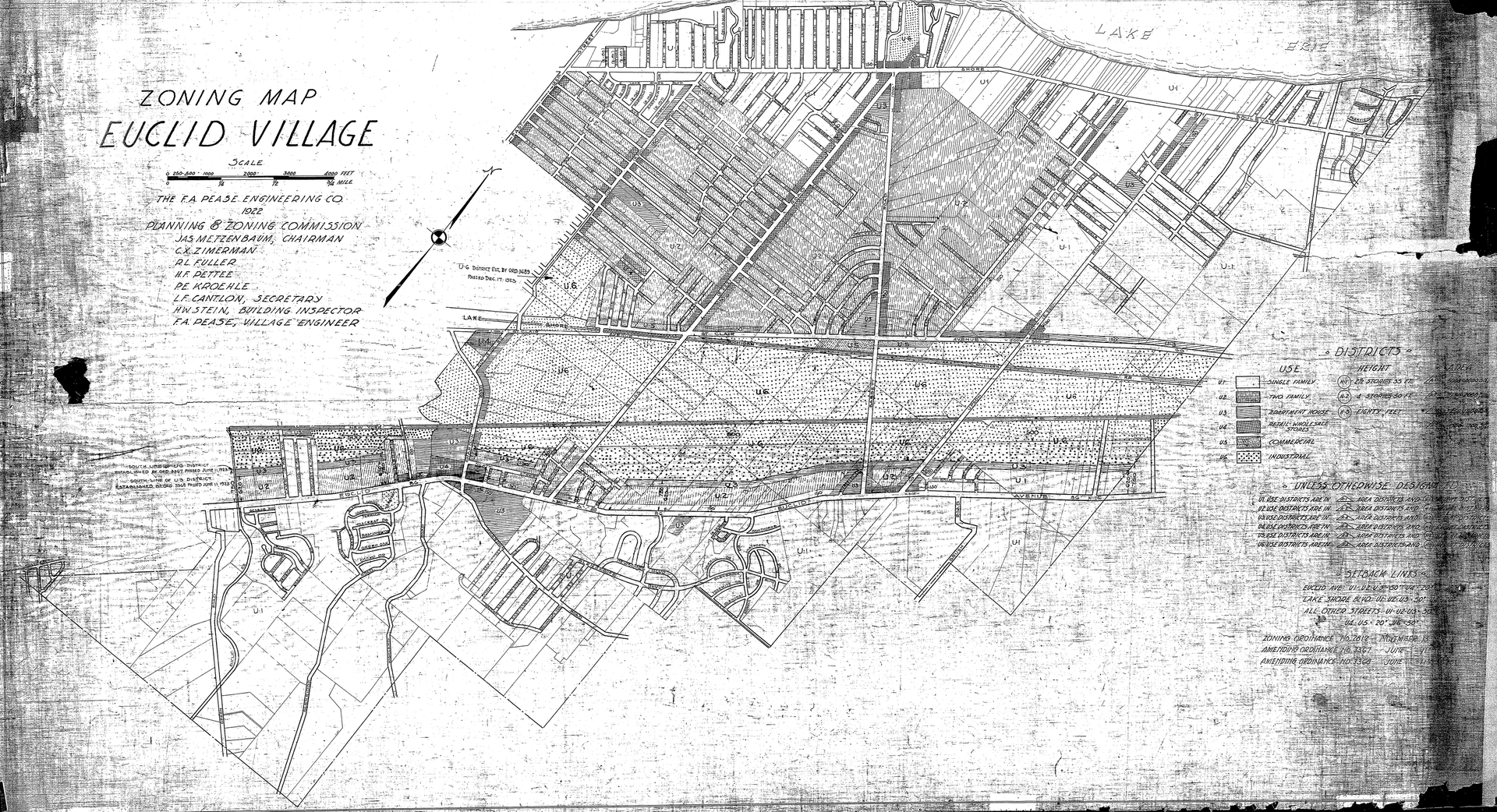

In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court bolstered zoning with another decision, Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co.

The Court ruled that zoning was a reasonable extension of municipal power. The decision gave legal standing to the zoning laws spreading across America.

The impact would be felt for decades. Zoning was and remains a powerful government tool to keep neighborhoods segregated. But segregation was also enforced privately, through restrictive covenants.

Restrictive covenants are rules imposed on property deeds and contracts. Often, these covenants set property requirements like approved paint colors or tree varieties.

But starting in the 1890s, restrictive covenants began to set rules around who could rent or buy a home.

These restrictive covenants were designed to exclude certain races, religions, and ethnicities—whether Chinese residents on the West Coast, or Black migrants in the urban North, or Jews on the East Coast.

They were born out of a common idea—based in racism—that all-White neighborhoods were better investments and places to live. Keeping areas homogenous, became the ideal for White homeowners.

But like racial zoning, restrictive covenants were challenged in the courts.

In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its Corrigan v. Buckley decision, ruling that restrictive covenants were constitutional because they were private contracts.

But in 1948, the Court struck down the legality of restrictive covenants in the case Shelley v. Kraemer. That did not immediately stop people from using them. It would take another twenty years for the federal government to put in place policies that effectively ended the practice.

Even so, once restrictive covenants were on property deeds, they were difficult to remove. Two decades later, the Federal Housing Authority was still granting mortgages on properties with restrictive covenants.

And today, there are an increasing number of states passing legislation to help homeowners to remove racially, religiously, and ethnically restrictive covenants from deeds.

“There goes the neighborhood!” Have you ever heard the phrase? What does it mean?

Do you live in a single-family home, a multiple-family building, or somewhere else? Do you own or rent? Do your neighbors’ homes look like yours?

Should local governments be able to control where people live?

In June 1910, W. Ashbie Hawkins, a Black lawyer, bought a house in one of Baltimore’s most prestigious neighborhoods. He rented it to his law partner George W. F. McMechen and his family. Both men were moving up in the world, part of an emerging Black middle class.

In 1910, Baltimore adopted one of the first residential racial ordinances, limiting home buyers to White blocks or Black blocks. The ordinance made Baltimore a national leader in segregation and encouraged other cities to pass similar legislation.

Courtesy of the New York Times Digital Archive

McMechen was the first Black resident on the all-White block. Neighbors responded with rage. They formed a neighborhood association and pushed the city of Baltimore to create the nation’s first racially based municipal segregation law. The law divided Baltimore into “white blocks” and “colored blocks.” Moving onto a block zoned for the other race brought a $100 fine and up to one year in jail.

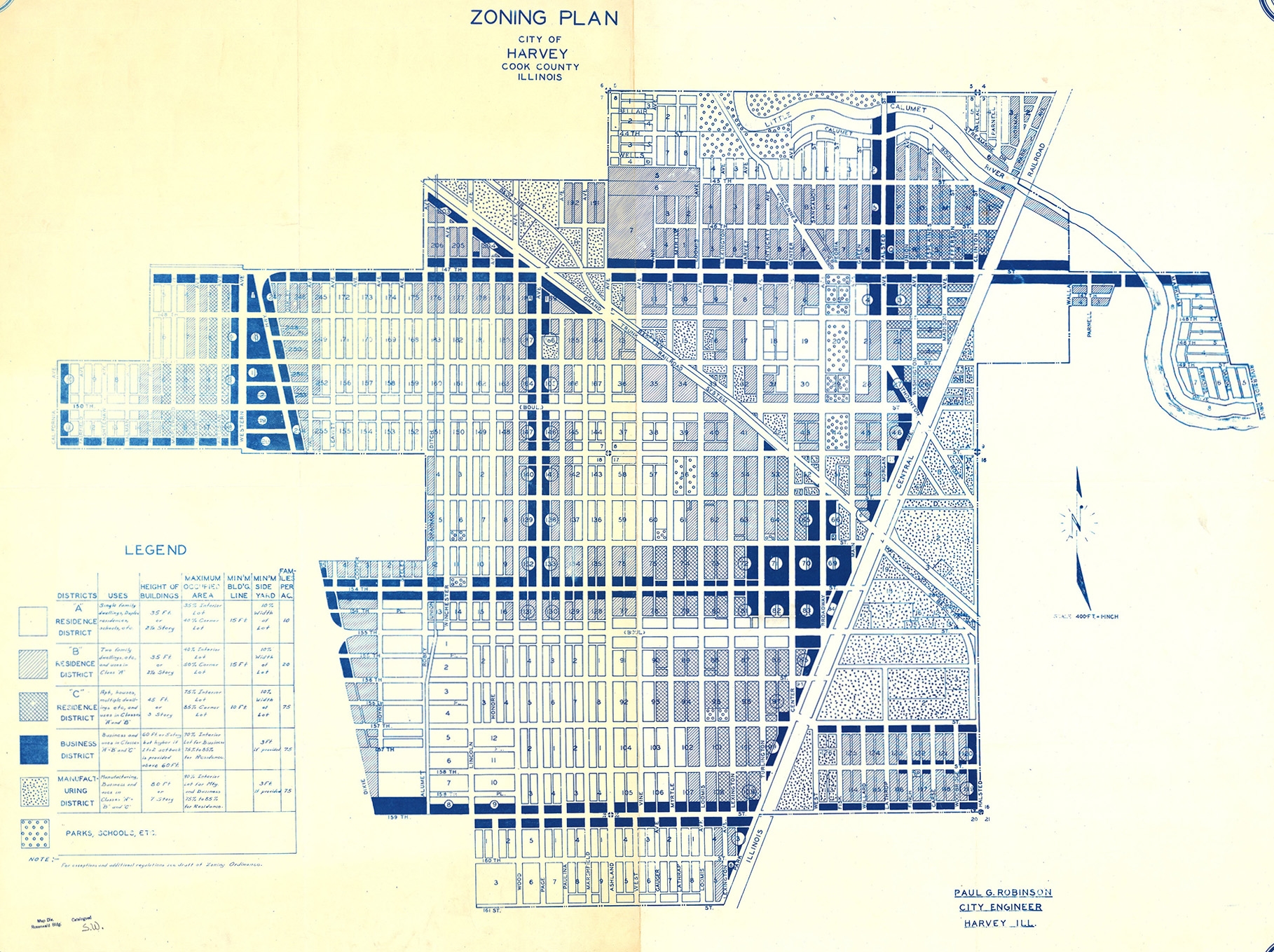

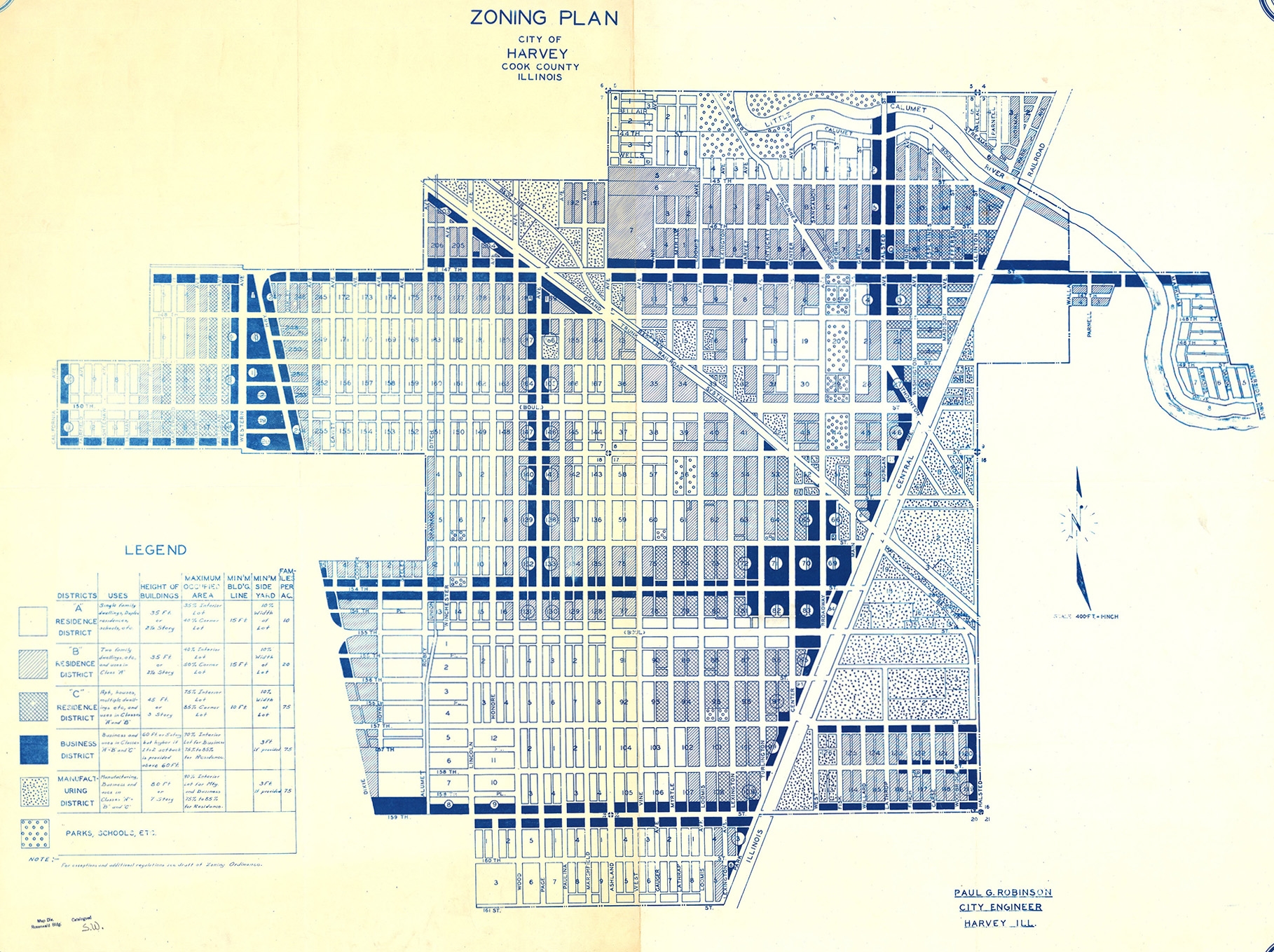

Baltimore’s law was an early instance of zoning.Zoning: A tool of city planning where cities are divided into specific zones with requirements for new development that set the zones apart from one another. Common zones are residential, business, and manufacturing/industry that can also include differentiation with zones for single-family homes or multi-family units among others. Zoning laws are local laws that draw boundaries around different districts and how properties within them can be used. Cities use zoning to arrange landscapes by function – designating living areas, business areas, open space, and manufacturing zones. Each zone may have different requirements for building size, fire protection, allowed activities, or even paint colors. Many of these regulations help make cities and towns safer, cleaner, more attractive places to live by, for example, separating heavy industrial zones from residential ones. But in cases like McMechen’s and many others, zoning has also been used to exclude.

An example of zoning, this map from Harvey, IL includes three types of residential districts (A-C), a business district, a manufacturing district, as well as land set aside for public use.

Courtesy of the University of Chicago Map Collection

Baltimore’s racial zoning ordinance failed several legal challenges, but the idea spread. Racially segregated zoning became popular in places where Black property ownership was increasing. In 1917, the city of Louisville, KY’s new racial zoning ordinance was swiftly challenged by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In Buchanan v. WarleyBuchanan v. Warley, 1917: A US Supreme Court decision that ruled that racially segregated zoning violated the 14th Amendment. (1917), the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with the NAACP, ruling that racially segregated zoning violated the 14th Amendment. Zoning could no longer restrict housing by race.

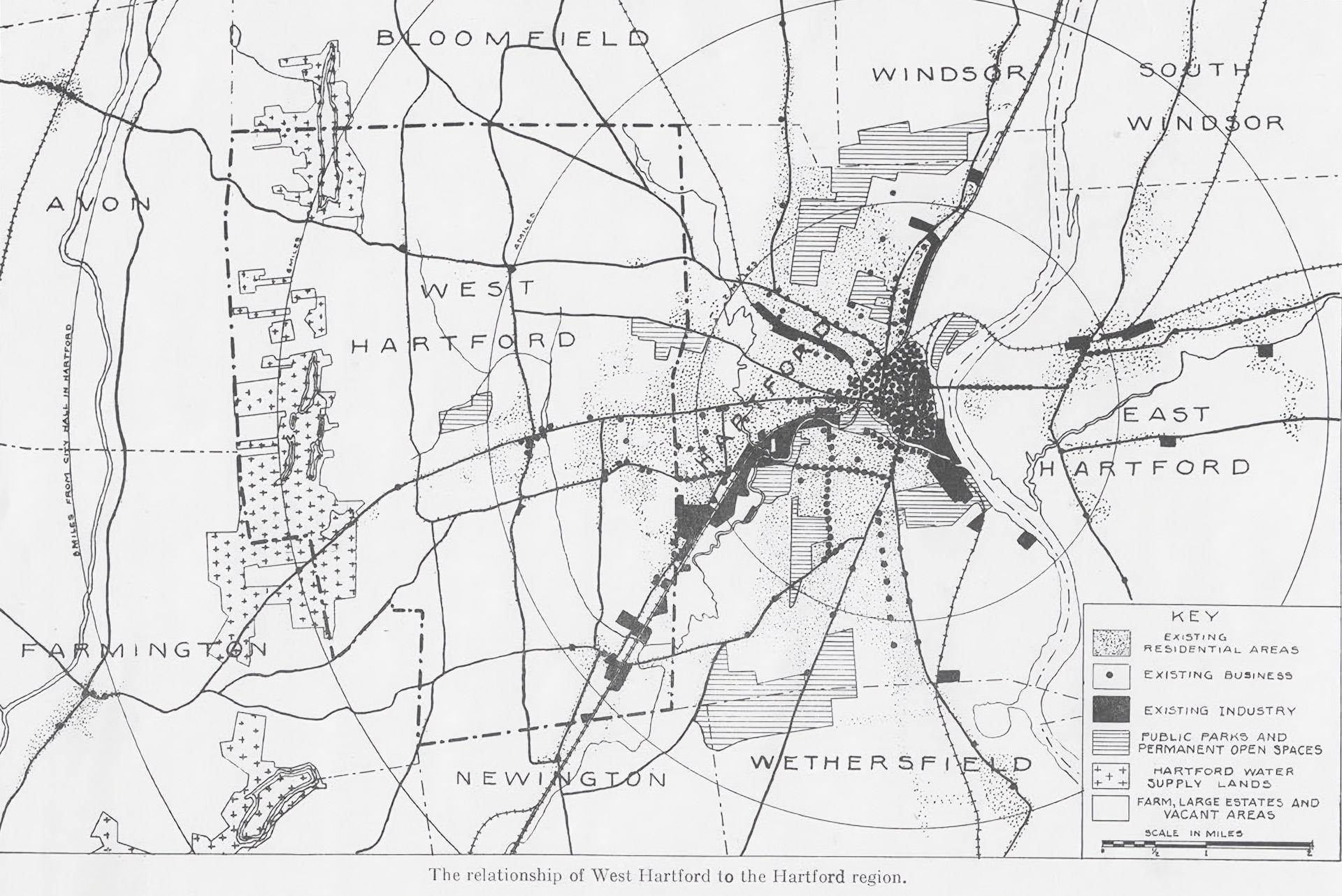

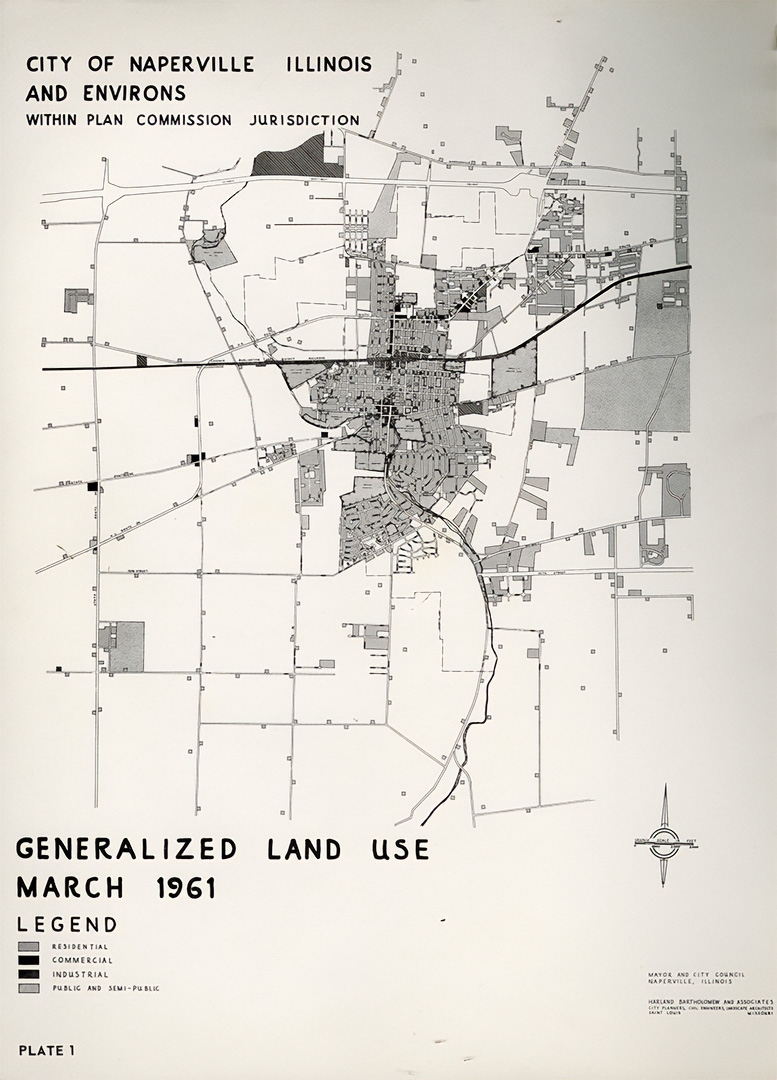

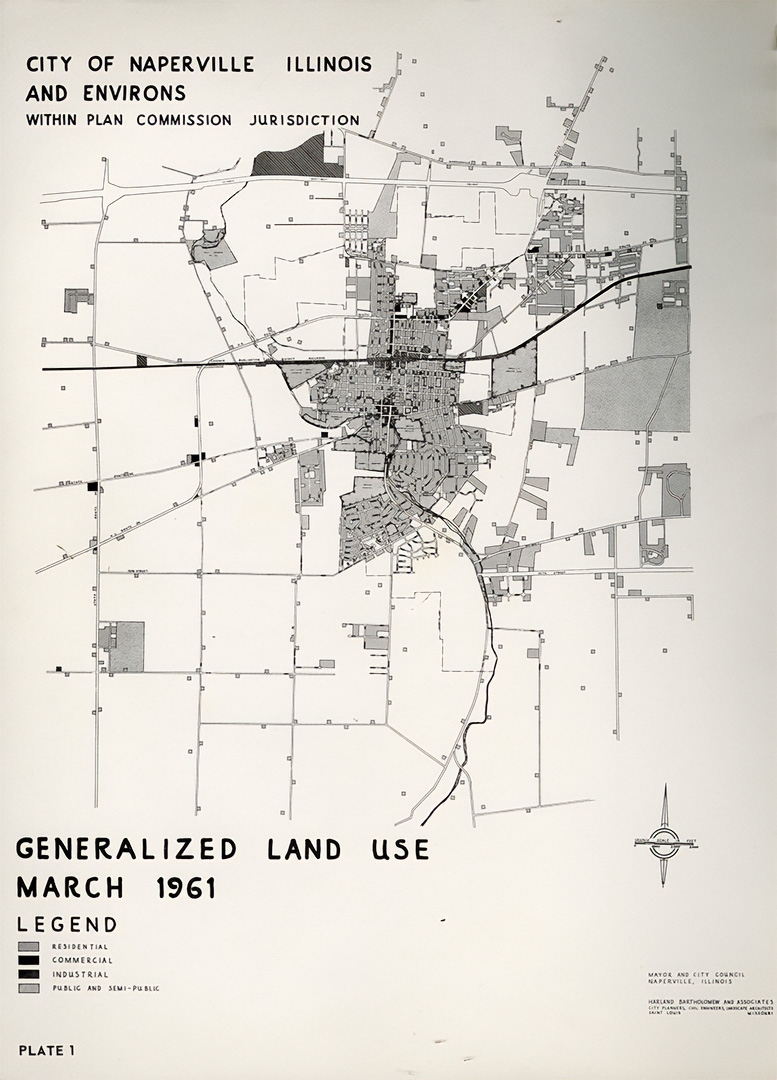

As seen in this 1961 map from Naperville, IL, zoning divides communities into residential, industrial, and commercial zones. Separating land use can make for more desirable living conditions, but it can also exclude people who cannot access their preferred home style or price.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

But cities still found ways to segregate using more indirect zoning. In 1919, the St. Louis city government decided that too many Black families were moving in and changed zones from residential to commercial so that no more housing could be offered. Seattle’s 1923 zoning ordinance designated zones commercial solely because Black and Chinese American families lived in them. Some rules set minimum and maximum lot and building size, or maximum number of housing units in a building. Other rules restricted how many people could live in one home and made it difficult to build multi-family homes, rental apartments, or smaller, more affordable homes.

At the time of the Buchanan v. Warley decision, only eight cities had zoning laws of any kind. 20 years later, more than 1,200 did. In 1926, a U.S. Supreme Court decision declared zoning a reasonable use of municipal power. Cities now had a legal endorsement for the widespread adoption of zoning, allowing them to plan and shape the future landscape.

The Village of Euclid established a zoning ordinance in 1922 to prevent the industrial expansion of Cleveland. Ambler Realty claimed that the ordinance limited the value of their land holdings by limiting its use and sued. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Village of Euclid, Ohio vs. Ambler Realty that municipal zoning was a legitimate extension of city police powers in 1926. This ruling provided support for thousands of zoning laws across the United States.

Courtesy of the City of Euclid, Ohio

In the 1970s, the NAACP launched a campaign to fight exclusionary zoning. They helped to argue the case of James v. Valtierra (1971), saying that Black and Mexican families in California were hurt by a requirement that affordable housing in certain zones had to be approved by popular vote. The US Supreme Court determined that requiring voter approval hurt all poor people and therefore was not racially discriminatory. Financial discrimination was not illegal. Modern housing advocates still struggle with a system that locks poor people out of many neighborhoods based on income, not race —even where the population of poor people includes a larger share of people of color.