Article 6

Racially Restrictive Covenants

Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri

What does it mean to call a neighborhood “exclusive?”

Who should be able to control who a person sells their property to?

Does your house have a restrictive covenant on the deed?

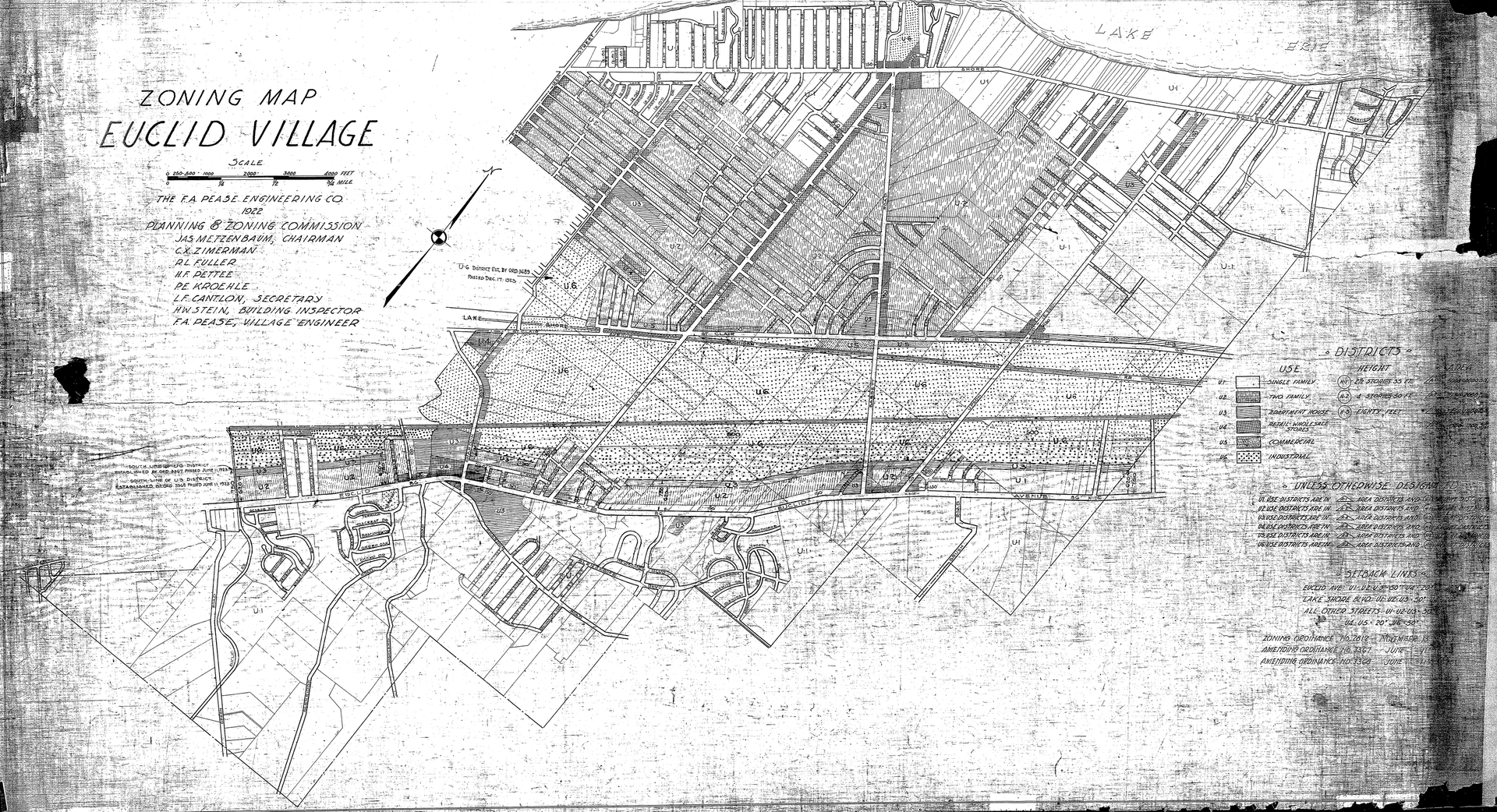

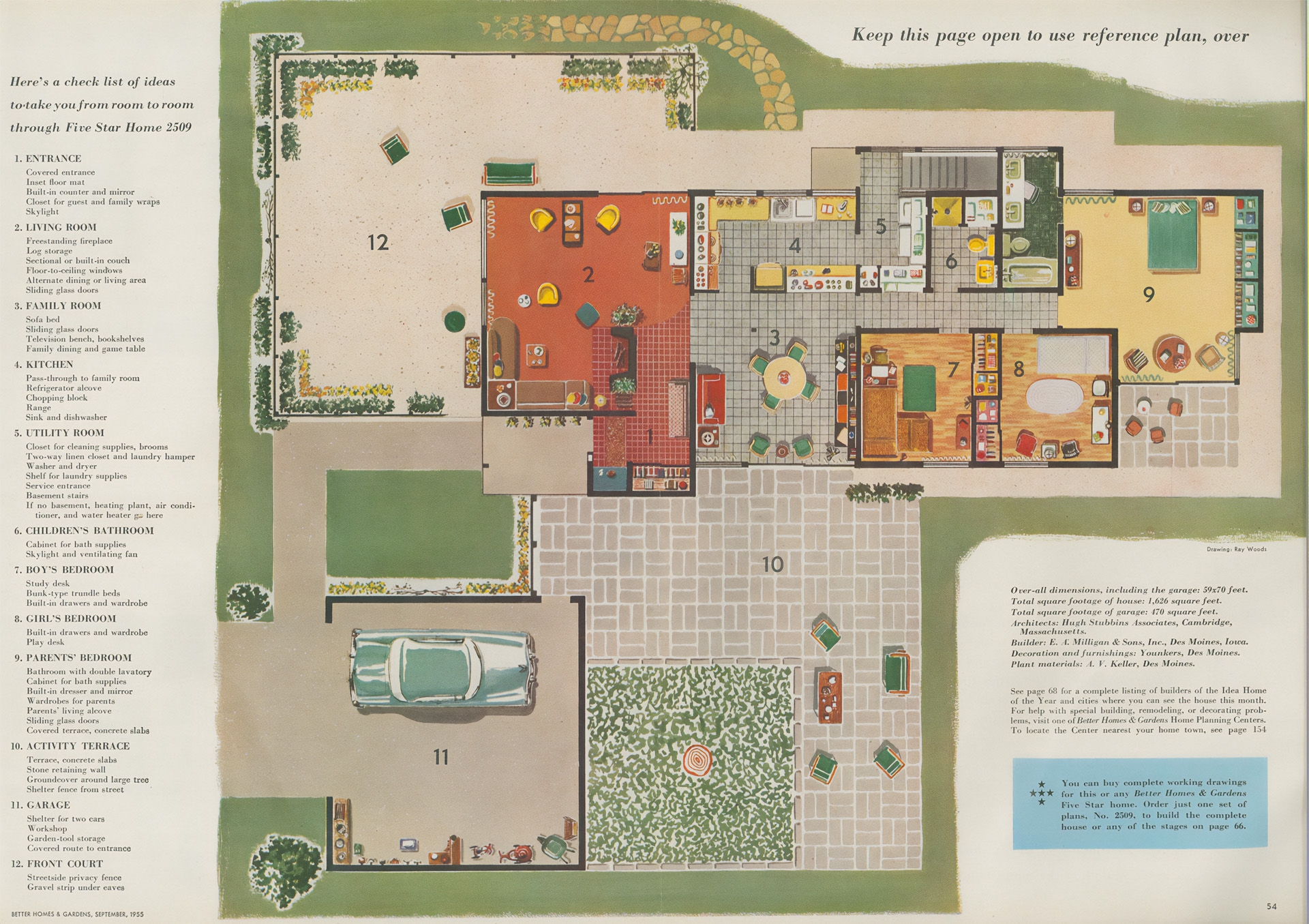

Zoning governs neighborhoods, but another level of exclusion was designed for individual pieces of property. Restrictive covenantsRestrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group. are agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Most home deedsDeeds: A deed is a written legal document which identifies individuals and other entities that have a claim to a property. Deeds are commonly associated with transferring property titles. include covenants. Often, they limit how a house can be used, whether more buildings can be added, or what the house looks like from the street. Covenants are a way to assure neighbors, buyers, and lenders that the value of their homes will not decline.

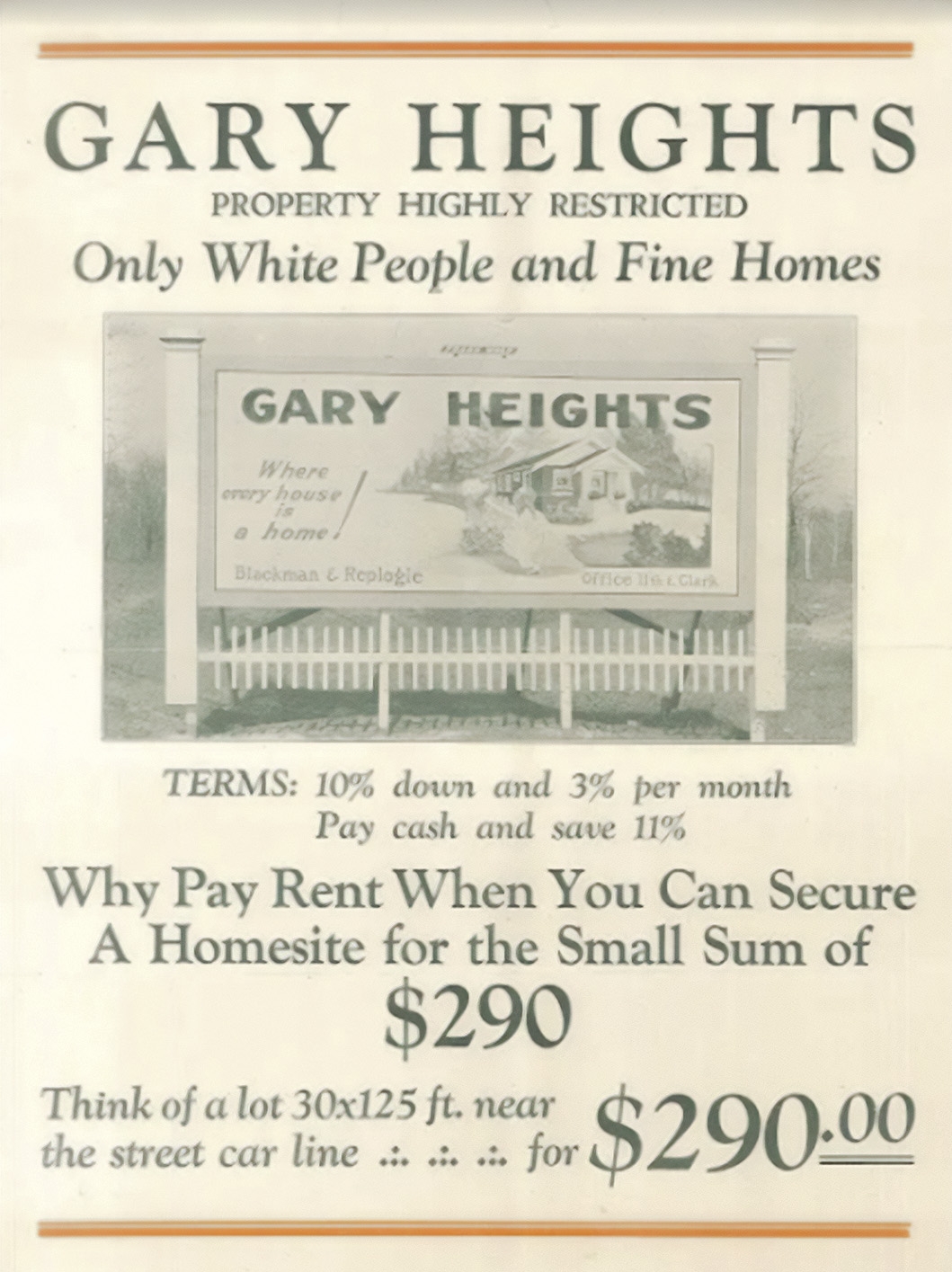

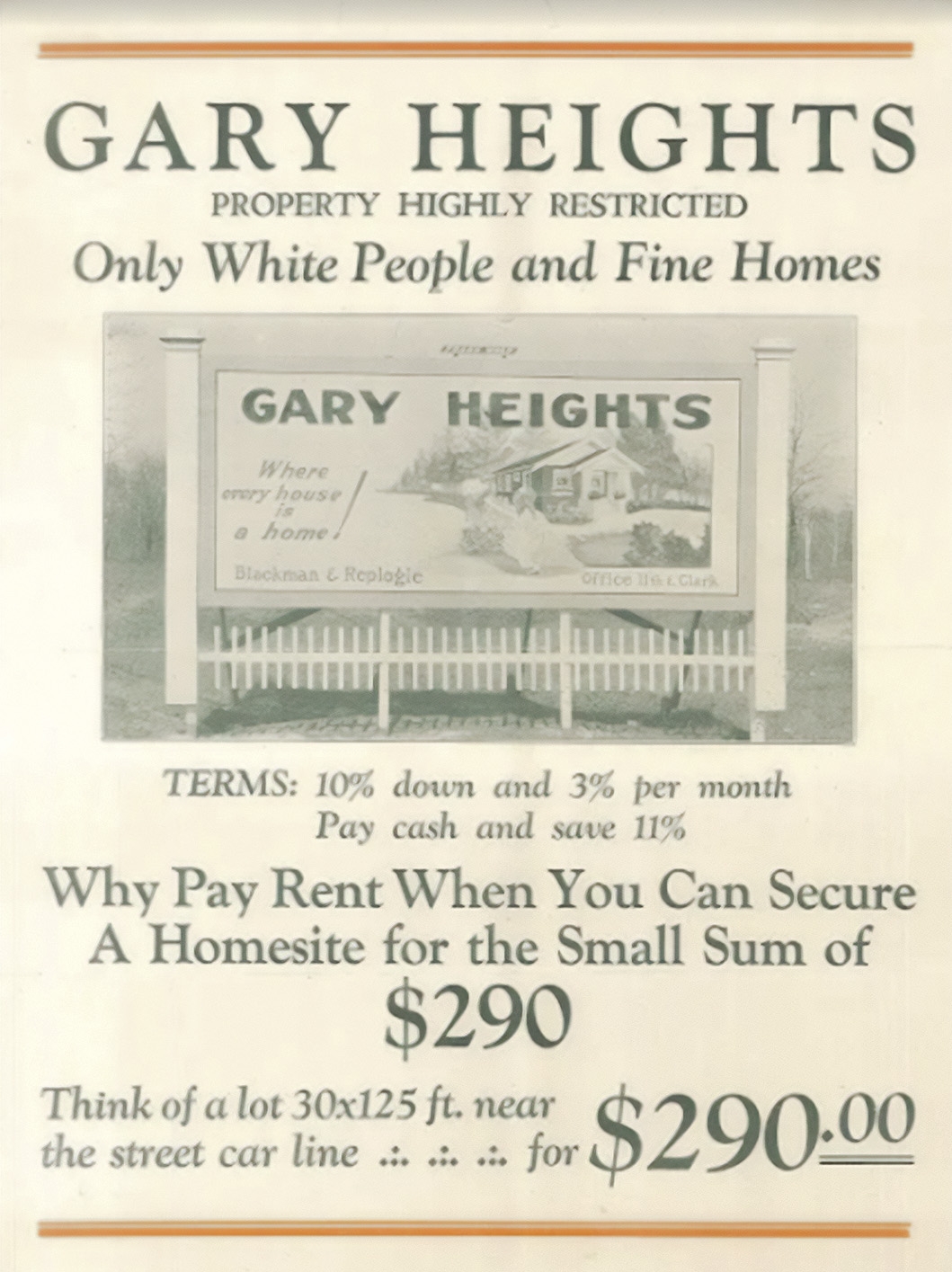

An advertising booklet for Gary Heights, Indiana, highlighting its restricted nature of "Only White People and Fine Homes" from the mid-1920s.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

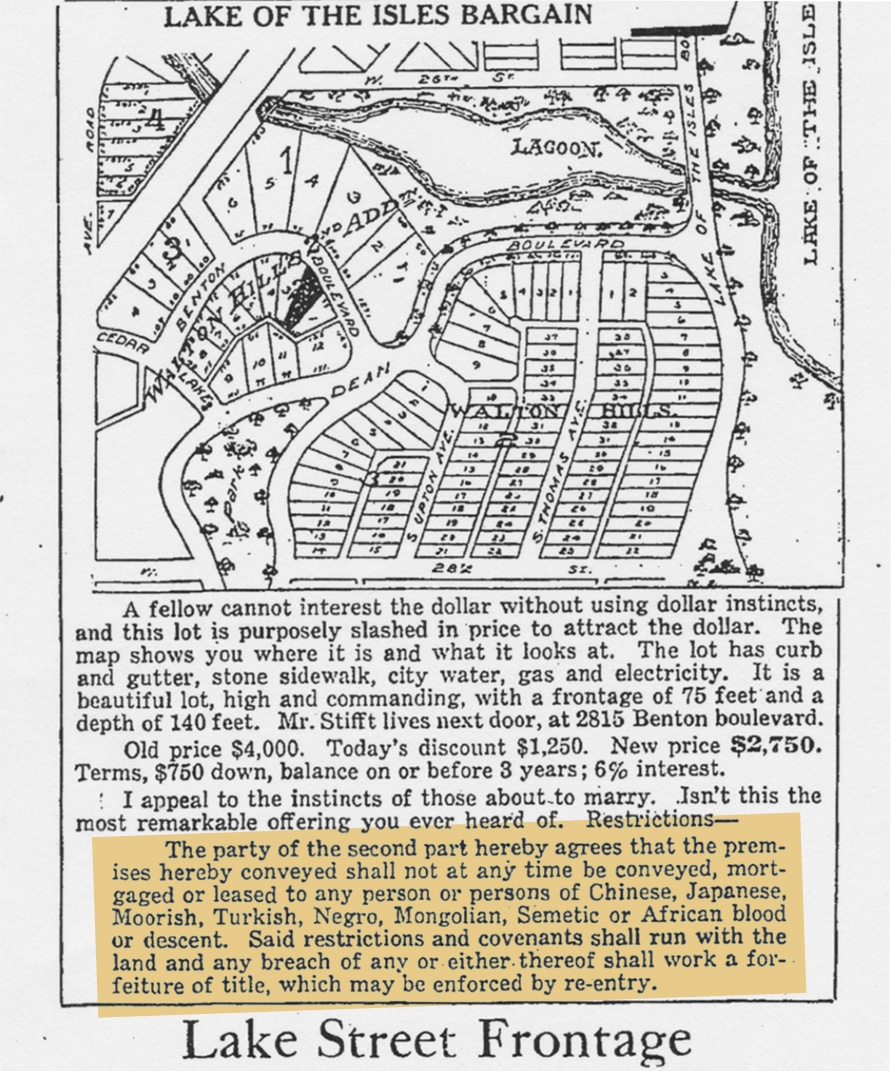

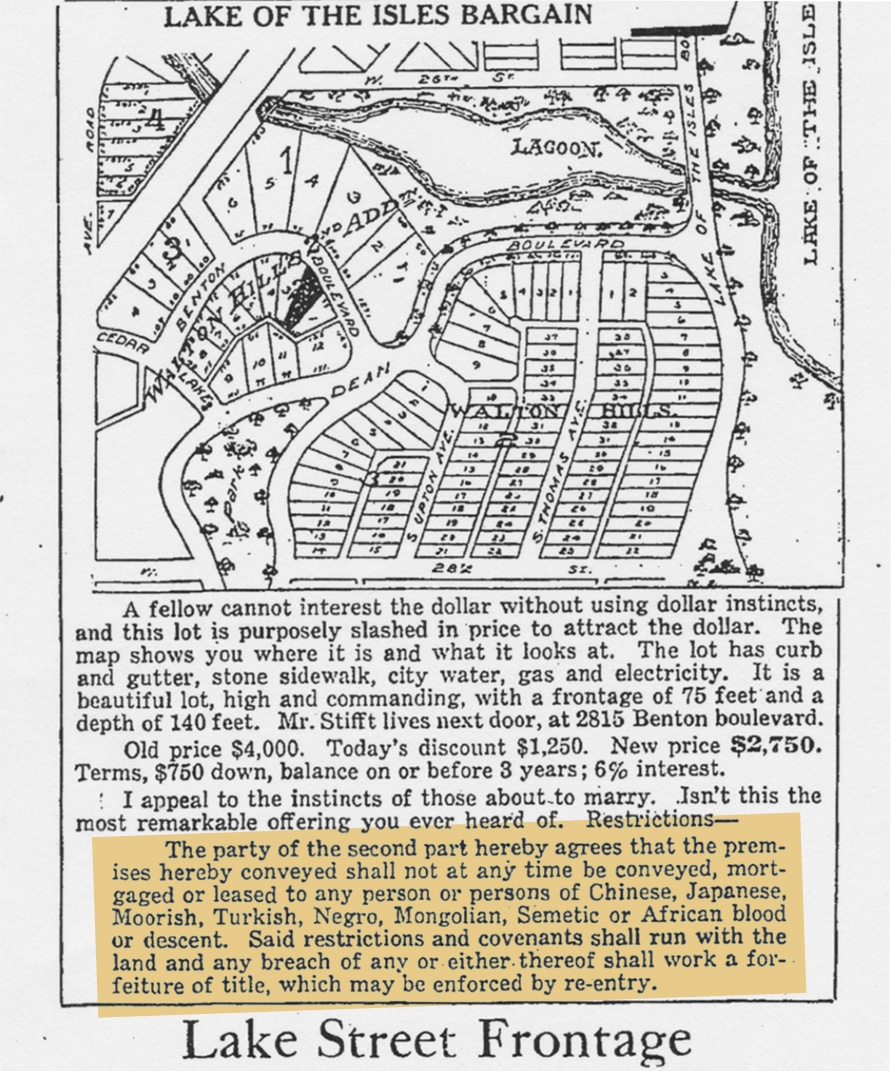

Starting in the 1890s, developers and lenders began adding covenants preventing the future sale of a property to certain buyers based on race, religion, or ethnicity. A typical covenant might say, “…hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be…occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race.” This language reflected White beliefs that people of other races were inherently inferior or even dangerous. Restrictive covenants often included words like “in perpetuity” to place those neighborhoods under White control forever. Developers advertised these homes as better places to live because of their “exclusive” community. In some places, White neighborhood associations enforced covenants with intimidation and violence.

Real estate advertisements broadcast their restrictions to make their developments attractive to potential White buyers, from the Minneapolis Morning Tribune, January 12, 1919.

Courtesy of the University of Minnesota

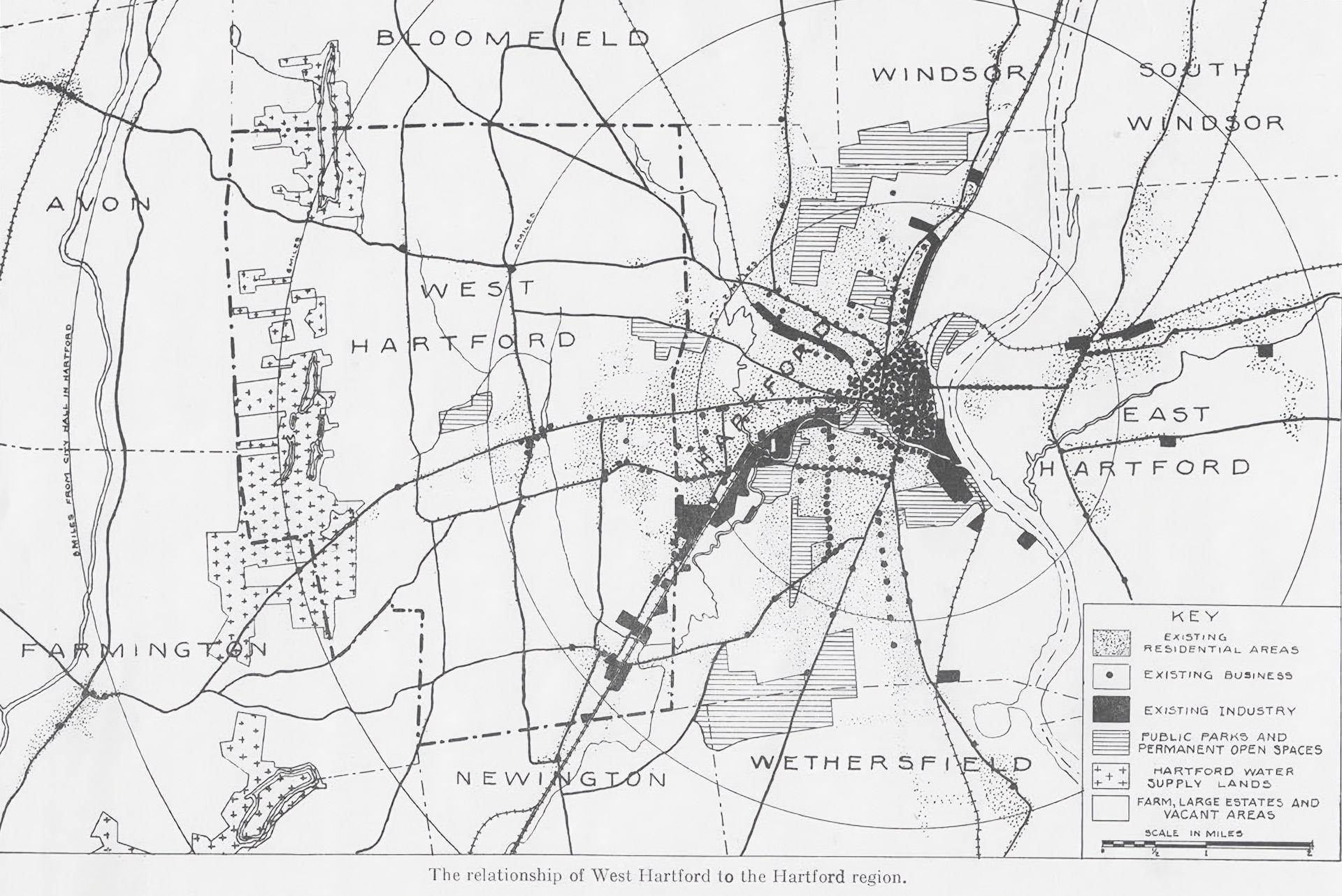

On the West Coast, some of the earliest restrictive covenants were used against Chinese Americans. As the Great Migration gained momentum, restrictive covenants became common in the North to prevent Black families from moving in.

As the Great Migration gained momentum, restrictive covenants became common in the North to prevent Black families from moving in.

When William and Daisy Myers moved into Levittown they experienced harassment, threats, and a cross burning. Some of their White neighbors attempted to intervene and the family received national support. Harassment gradually declined as it was clear they were not leaving.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The legality of racially restrictive covenants was tested in a 1926 U.S. Supreme Court case, Corrigan v. Buckley.Corrigan v. Buckley, 1926: A US Supreme Court decision that upheld racially restrictive covenants asserting that private contracts were not subject to the 14th Amendment. Irene Corrigan, a White woman in Washington, D.C., sold her home to a Black couple. She was sued by a group of 30 White neighbors for breaking a racially restrictive covenant on the deed. The Supreme Court sided with the neighbors, ruling that a housing sale was a private contract not governed by the 14th Amendment.14th Amendment: The 14th Amendment to the US Constitution granted newly emancipated Black Americans citizenship as well as equal protection under the law. These legal and civil rights did not equally apply to women until the passage of the 19th Amendment. The decision affirmed that racially restrictive covenants were legal. People from restricted groups who had managed to buy restricted property could now be sued and lose their homes.

The Country Club District is a series of upscale residential neighborhoods outside of Kansas City, Missouri. Developer J. C. Nichols included racially restrictive covenants on home deeds, preventing Black Americans from purchasing homes.

Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri

Civil rights activists continued to fight restrictive covenants. In 1948, they brought the case of Shelley v. KraemerShelley v. Kramer, 1948: A US Supreme Court decision that ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. It did not remove them from property deeds and many remain on deeds to this day. to the U.S. Supreme Court. A Black couple, J.D. and Ethel Lee Shelley, bought a home in St. Louis with a restrictive covenant against “people of the Negro or Mongolian race.” They were sued by a White neighborhood association. In its ruling, the Supreme Court did not challenge the private nature of the contracts, but did require states to enforce equal protection, as promised in the 14th Amendment. That made it legally impossible to use lawsuits or police to enforce racially restrictive covenants.

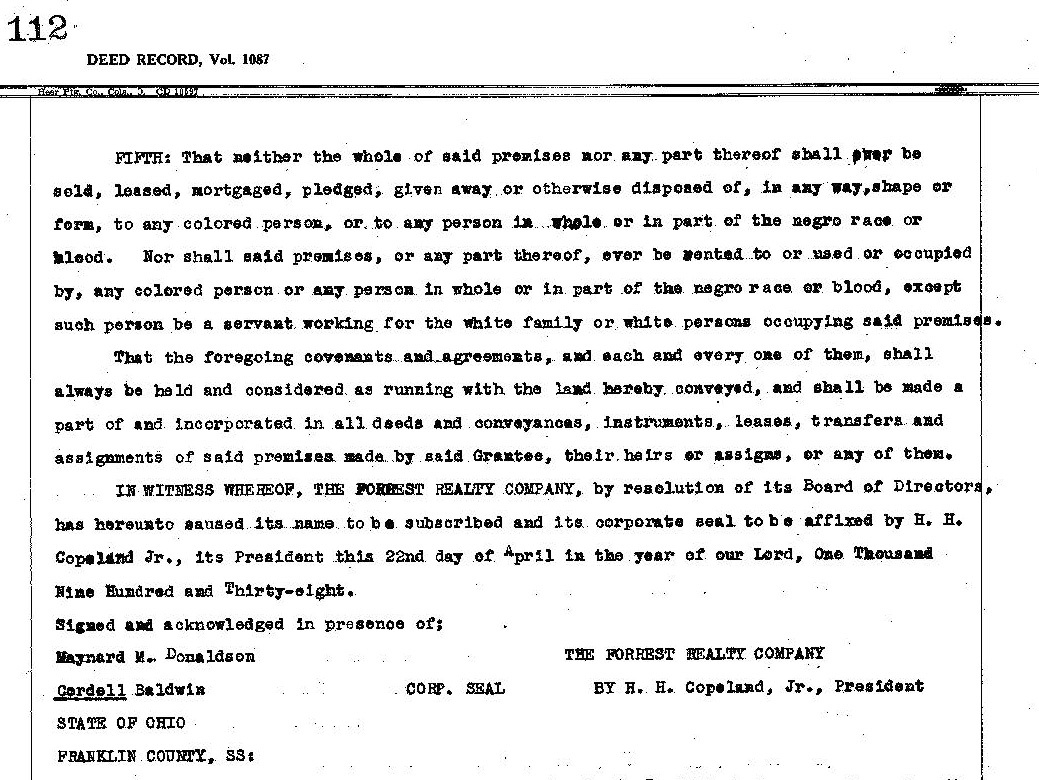

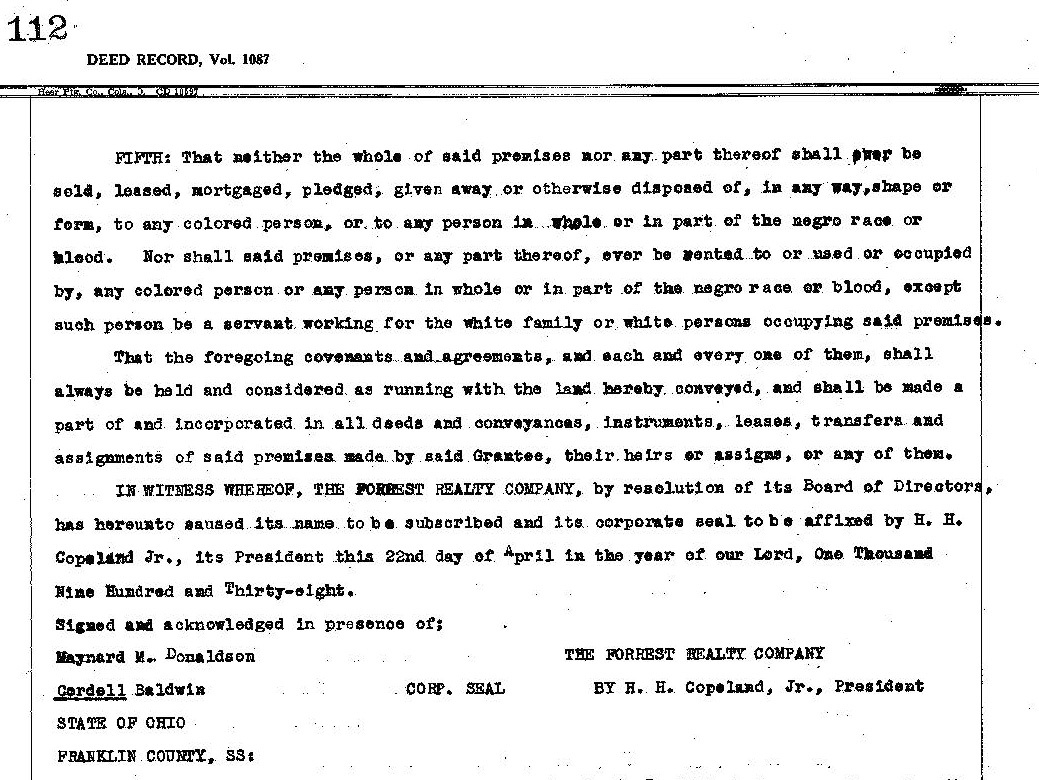

Restrictive covenants on deeds such as this one from Bexley, Ohio illustrate the type of language used to limit roles of Black people to servitude and exclude them as residents.

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection

Housing activists, homeowners, and lawyers worked for more than 20 years to make private discrimination illegal. Still, racially restrictive covenants continued to appear on deeds. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) granted mortgages to deed-restricted properties until the 1960s. Since deeds are not often revised, covenants still exist on many of them. Recently, a national movement for deed scrubbing has inspired people to find and remove ethnic, racial, and religious restrictive covenants on deeds for their own properties.