Article 11

Living and Losing in the City

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

What is White flight?

Should old buildings be razed to make way for the new? Whose homes should be the first to go?

Can good intentions sometimes create bad outcomes?

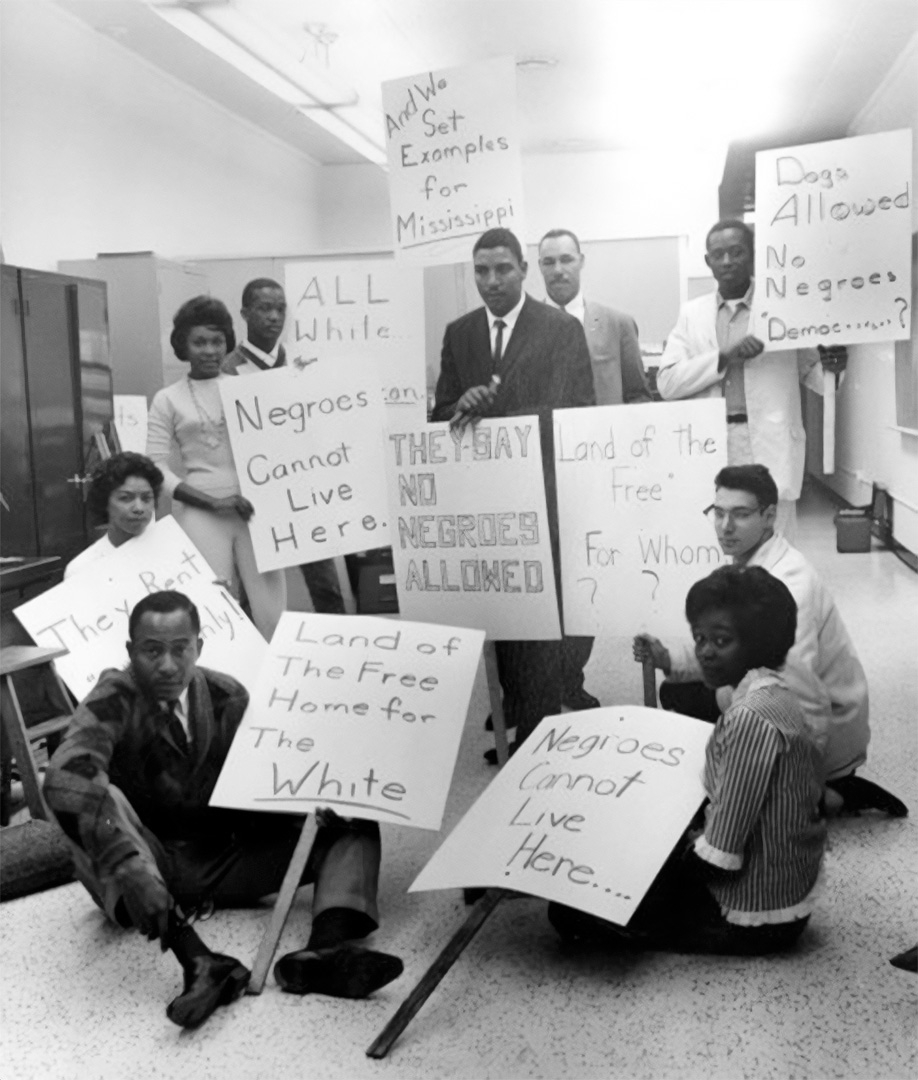

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) protests conditions in slum housing in New York City in 1964.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

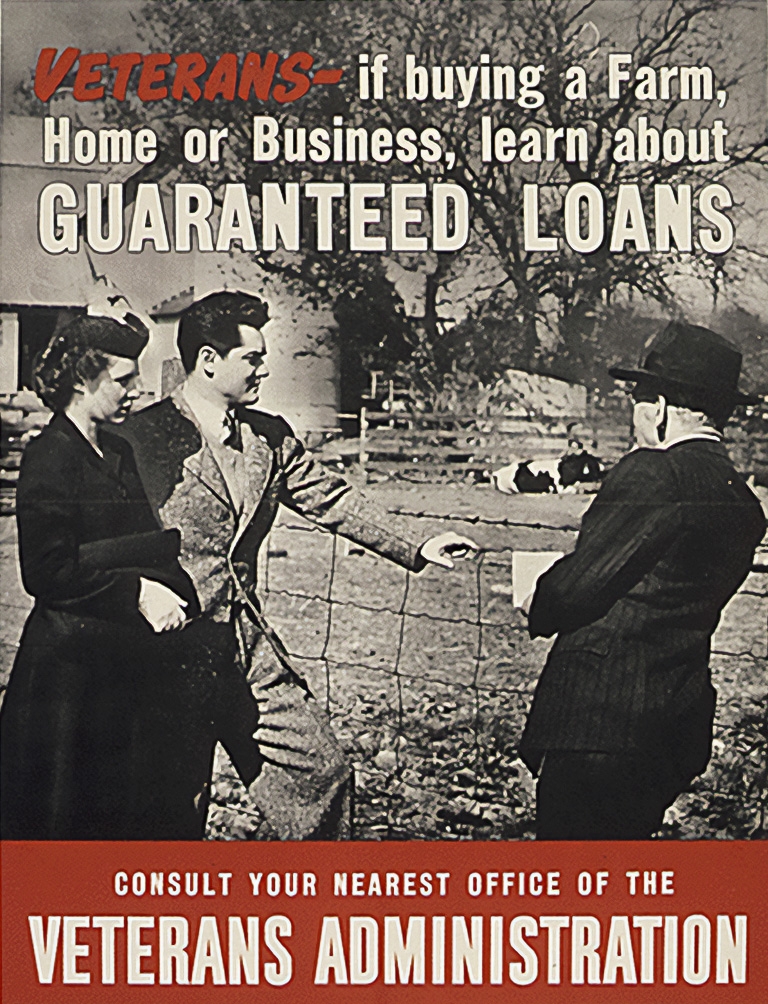

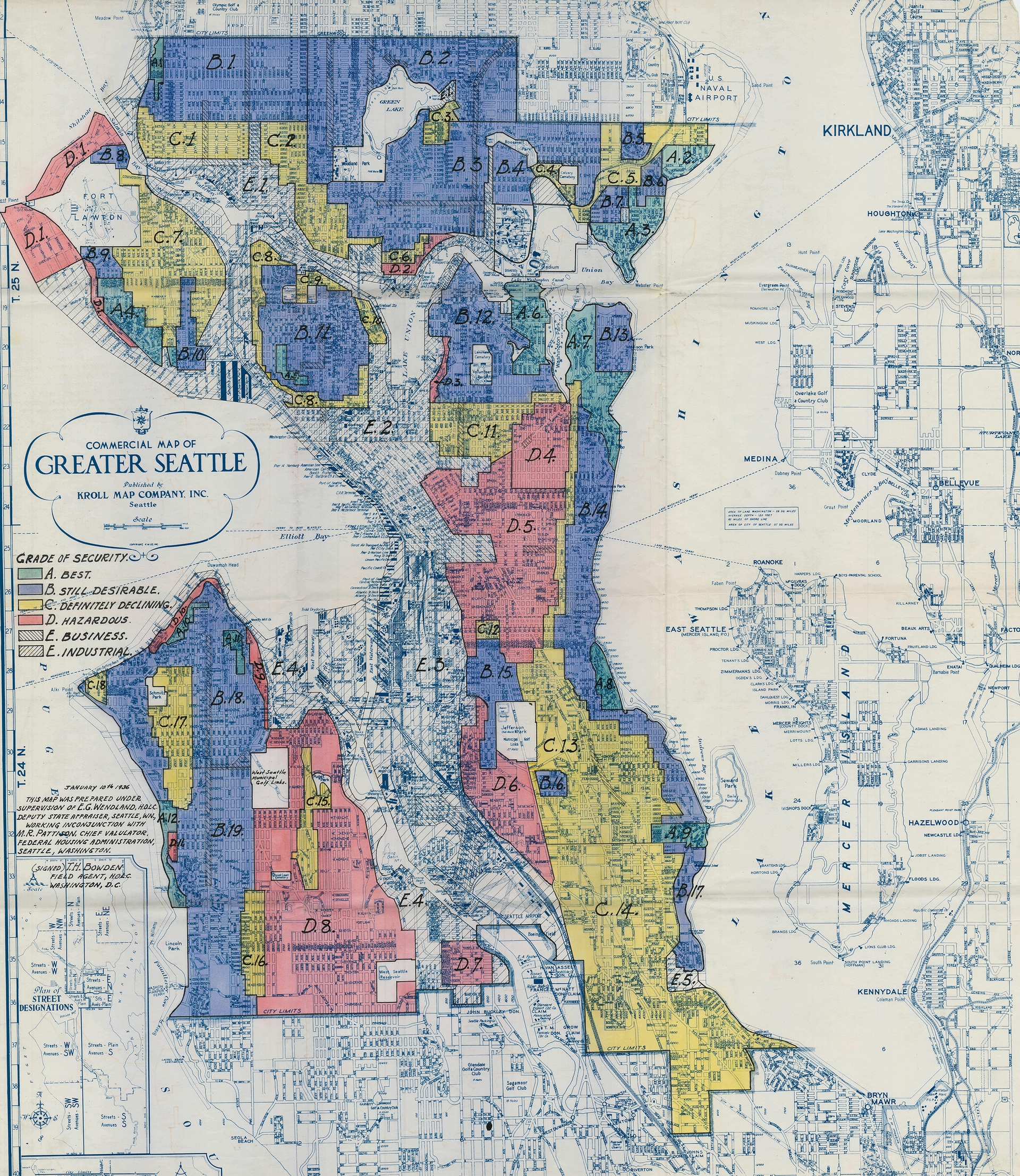

As suburbs boomed, America’s cities deteriorated. After a century of growth, cities began losing residents to the suburbs. In a major migration known as White flight,White Flight: The process by which White Americans, driven by the fear of rapidly shifting neighborhood demographics, moved in large numbers to different areas. In the mid-twentieth century US, this process often involved White Americans abruptly moving from urban areas to new suburban developments leaving more economically vulnerable communities of color left in cities which were experiencing disinvestment. White people used growing wealth and new home loan access to move out of the cities. In some places, Blacks also fled to the suburbs. As the number of Black professionals multiplied, middle-class Black families, able to afford houses in White neighborhoods, moved beyond Black districts. But many suburbs that attracted Black buyers soon experienced a suburban version of White flight. When they left, middle-class White and Black families took their higher average incomes, tax contributions, and power to invest along with them. Cities were left poorer and less diverse. Even during the Great Migration, about two White people left the city for every Black person who moved in. The overall population of center cities decreased by 25%.

Highways, public housing, and urban renewal pushed the dual housing markets even farther apart.

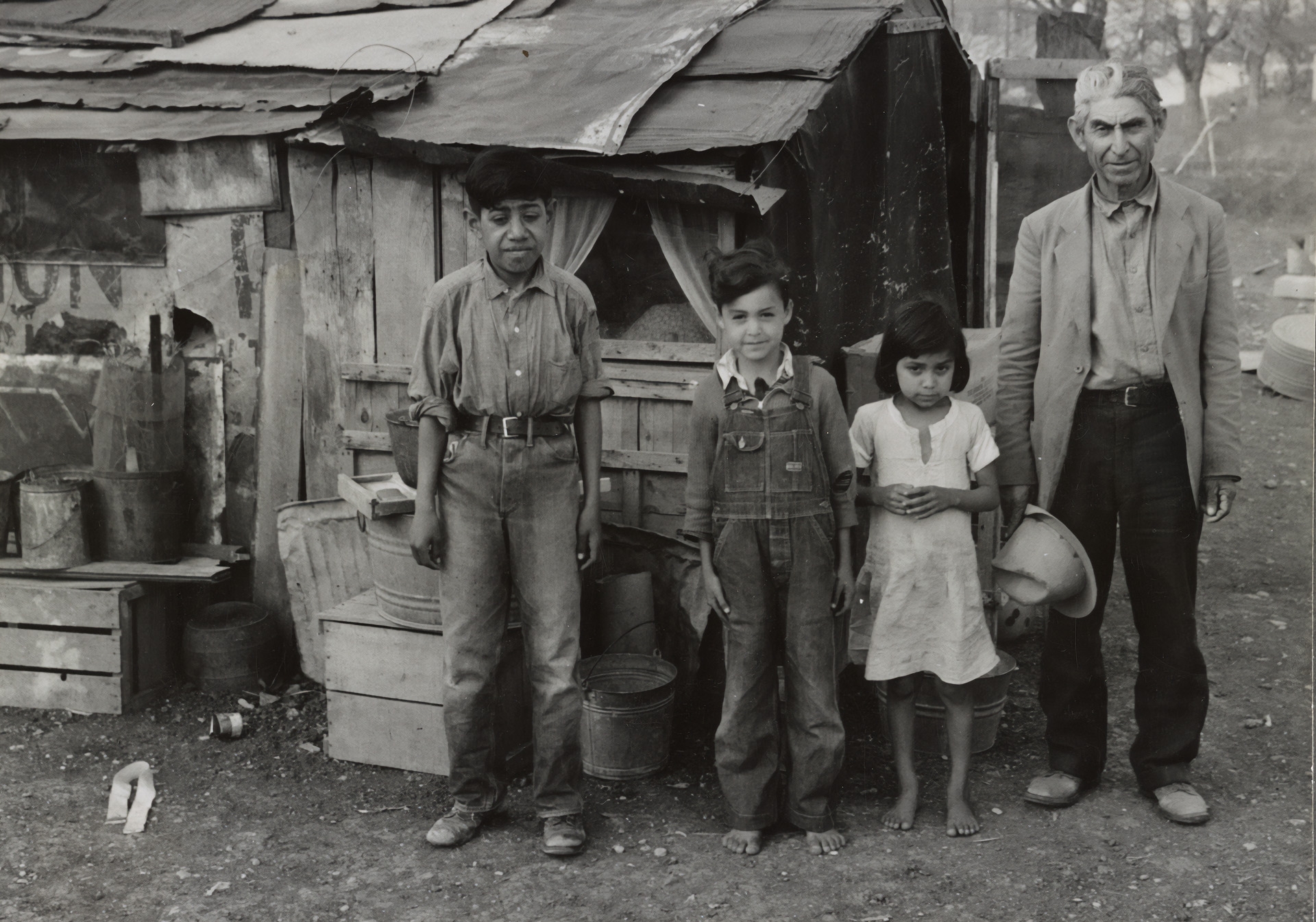

Senor Vigues and three of his five children outside of their homemade shack home opposite Santa Rita Courts, an early segregated public housing project. Located in Austin, Texas the project was one of the first to be completed under the Housing Act of 1937 and was constructed for Mexican American families.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Those who stayed saw their cities decline. Their homes and neighborhoods had not seen new investment in decades. Dilapidated buildings, ancient plumbing, and broken fixtures were a way of life in what officials now called slum housing. The federal government developed programs to improve matters, but in the end, they only made segregation worse.

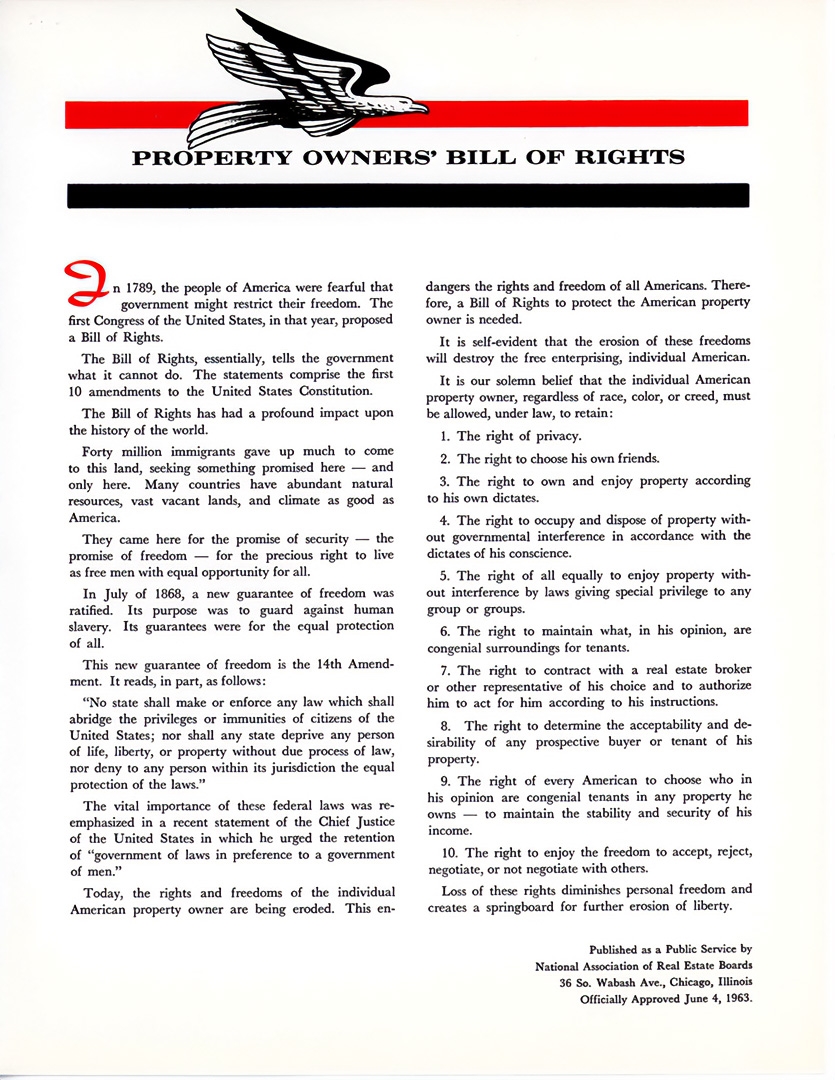

The National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) completed this Property Owner's Bill of Rights in 1963. The document advances segregation by connecting American ideals of freedom with property ownership and the rights of homeowners, neighbors, and realtors.

Courtesy of the National Association of REALTORS®

Public housing was one effort. Using public money, the government paid cities to demolish old slum housing and rebuild new, publicly owned housing for low-income renters. The Housing Act of 1937 provided $800 million for 587 of these new developments. To avoid competing with local investors, the government enforced rules that required cities to maintain the existing racial balance and not to build on empty land that might become valuable. Instead, most projects tore down existing buildings—homes to thousands of people.

Resource

A history of the relationship between government and housing and the debate over public housing.

Approximately 15,000 people lived in Cabrini-Green (the Frances Cabrini Rowhouses and Extension and William Green Homes) at its peak. Cabrini-Green became synonymous with the failures of public housing. From 1995-2011, the Chicago Housing Authority tore down the mid- and high-rise buildings. Only the rowhouses remain.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The 1949 Housing Act aimed to provide “a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.” It promised one billion dollars to improve cities through urban renewal.Urban renewal: A program of seizing deteriorated or slum neighborhoods in urban areas with the intention of knocking them down and rebuilding and modernizing infrastructure to attract new businesses, better housing, and more public and private investment. It occurred around the world during the twentieth century. From 1949 to 1974, the US federal government provided financial support for these programs that reshaped cities and displaced many people of color and poor residents. In these plans, the government used its power of eminent domainEminent domain: The right of a government or government agent to seize private property for public use with a compensation payment. to declare sections of land blighted and seize it for redevelopment. Then, the government contracted with private developers to use the land to build completely new neighborhoods. More than one million people, two-thirds of them Black or Puerto Rican, were forced to leave their homes for urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s. Developers and the government promised funds and relocation assistance, but they rarely followed through. People were left to find housing on their own, cramming into already overcrowded neighborhoods or leaving the city entirely. Writer James Baldwin observed that urban renewal really meant “Negro removal.”

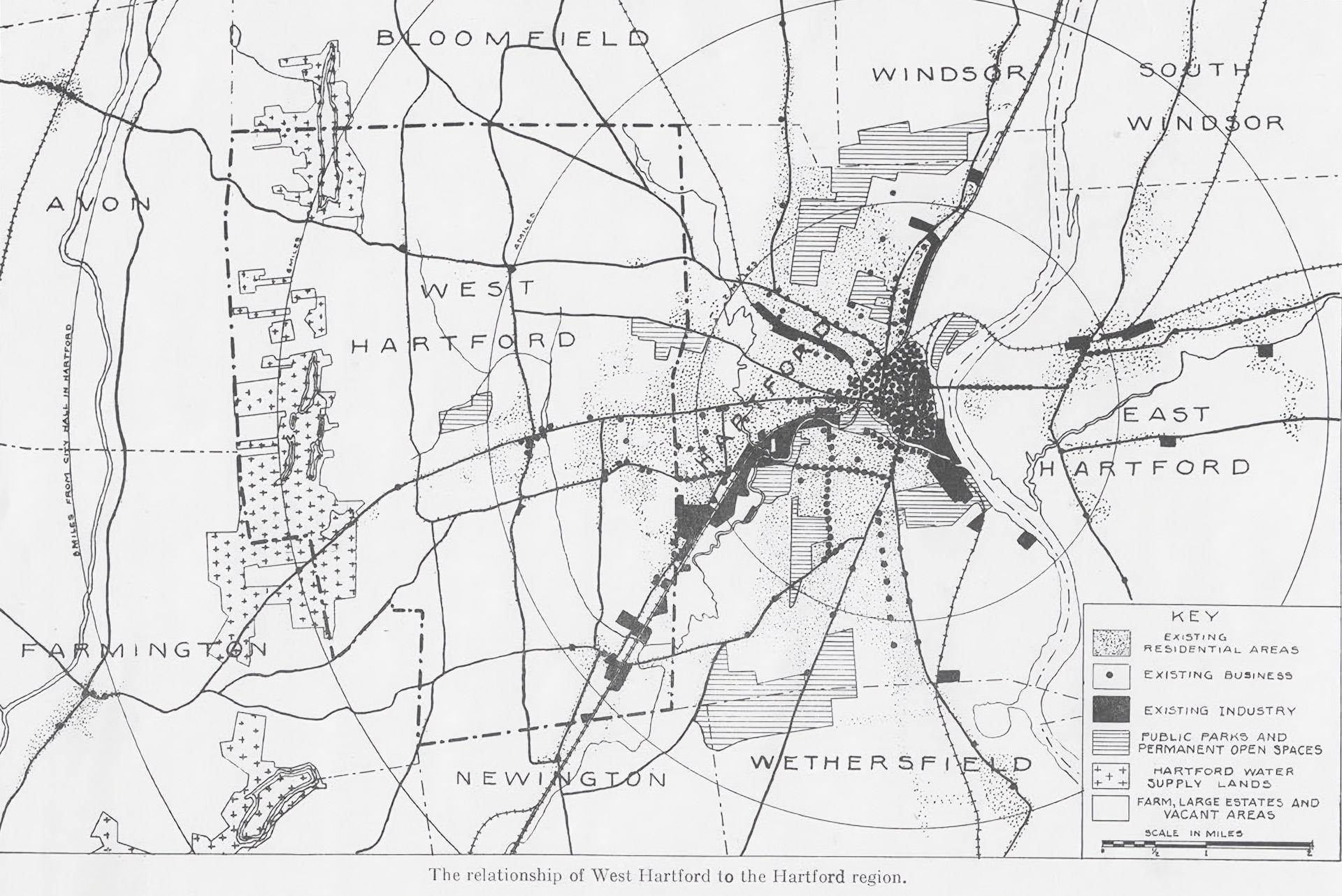

New highways also shattered city neighborhoods or wiped them off the map completely. Suburbs depended on fast roads for commuting to city centers. After the Federal Highway Act of 1956, 41,000 miles of new interstate highways spread over the nation. Highway planners routed roads through the centers of cities without concern for what was in the way. In city after city, White-majority neighborhoods were spared while Black and Hispanic ones were demolished or cut in half by high-speed roads. In Detroit, the thriving Black business district of Paradise Valley was bulldozed to make way for Interstates 75 and 375. In Columbus, Ohio, construction for I-70 destroyed the Black Near East Side while leaving Bexley, the White neighborhood just to the north, untouched. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Hill District lost more than 400 businesses and 40,000 residents to make way for I-579.

Highways, public housing, and urban renewal pushed the dual housing markets even farther apart. Suburban housing, mainly available to White people, boasted new construction, open space, and convenient highways. The urban market was a messy mix of older buildings, public housing, unaffordable new luxury districts, and redlined neighborhoods where minority residents were concentrated. In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made a landmark speech that connected prosperity in the suburbs to poverty in the ghetto. Unless housing discrimination came to an end, he said:

There can be no lasting escape for those of you who have fled behind the suburban curtain, for your Black brother yet languishes in the slums, crying out to you. Your lot is inextricably interwoven with his, since he retains the capability of ringing down the curtain on the American Dream. A minority that is sick with despair can poison the wellsprings from which the majority, too, must drink.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., ActivistDespite King’s urging, the flow of investment from city to suburb remained largely unrecognized by most White Americans.

Additional Resources

A history of the relationship between government and housing and the debate over public housing.