Article 12

Taking to the Streets

Taking to the Streets

ViewHide Transcript

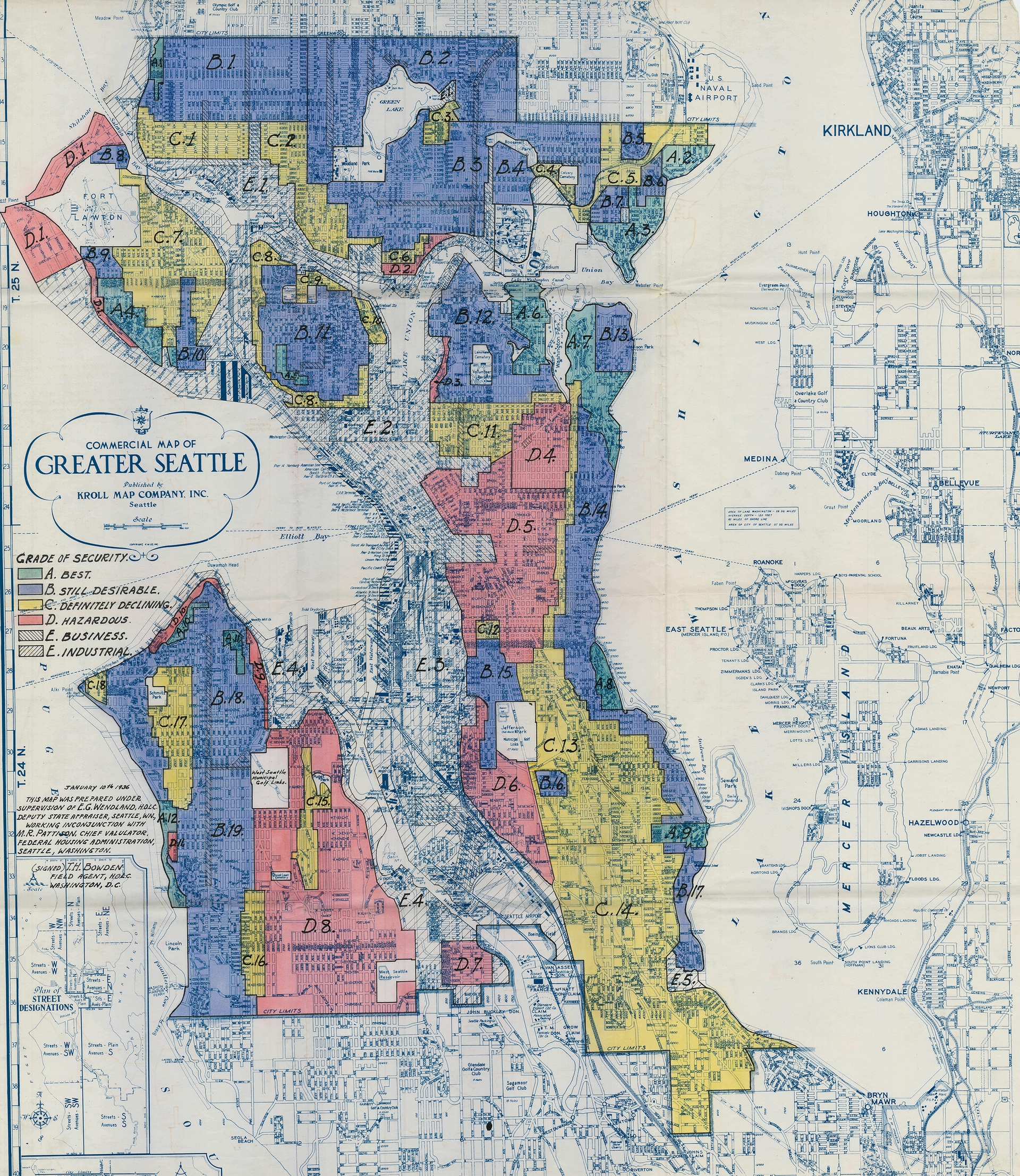

Between 1890 and 1950, the segregation and isolation of communities of color deepened.

But there were always those who fought back.

Although most Americans are familiar with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the seeds of that movement were sown a century earlier. In fact, the first Civil Rights Act entitling all Americans to full and equal enjoyment of public accommodations passed in 1875, only to be repealed by the US Supreme Court in 1883.

At the turn of the twentieth century, people began organizing in new and unified ways to attain full civil, economic, and social rights.

Some resistance was born out of the church. Religion had long been a powerful source of unity for Black communities, and Black congregations challenged Jim Crow laws, segregation, and violence.

Between 1890 and 1910, the number of Black professionals doubled, and more and more middle-class Black families moved into White neighborhoods.

Though many were met with fierce resistance, others became pioneers forging strong communities in urban spaces. On the forefront of the battle for Black civil rights was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP.

In 1909, Black leaders including W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell and White activists founded the NAACP to challenge discrimination and violence.

Within a decade, there were more than 90,000 members across 300 branches. The NAACP took the fight against residential segregation to the courts, with cases challenging racial zoning and restrictive covenants.

The era would see the founding of more organizations working to protect the rights of people of color including the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1896, and the National Urban League in 1910. In 1913, The Anti-Defamation League was founded to fight the escalation of anti-Semitism, including violence against Jewish businesses and religious institutions that was inspired by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

As Black people advocated for their rights, white supremacists reacted with violence.

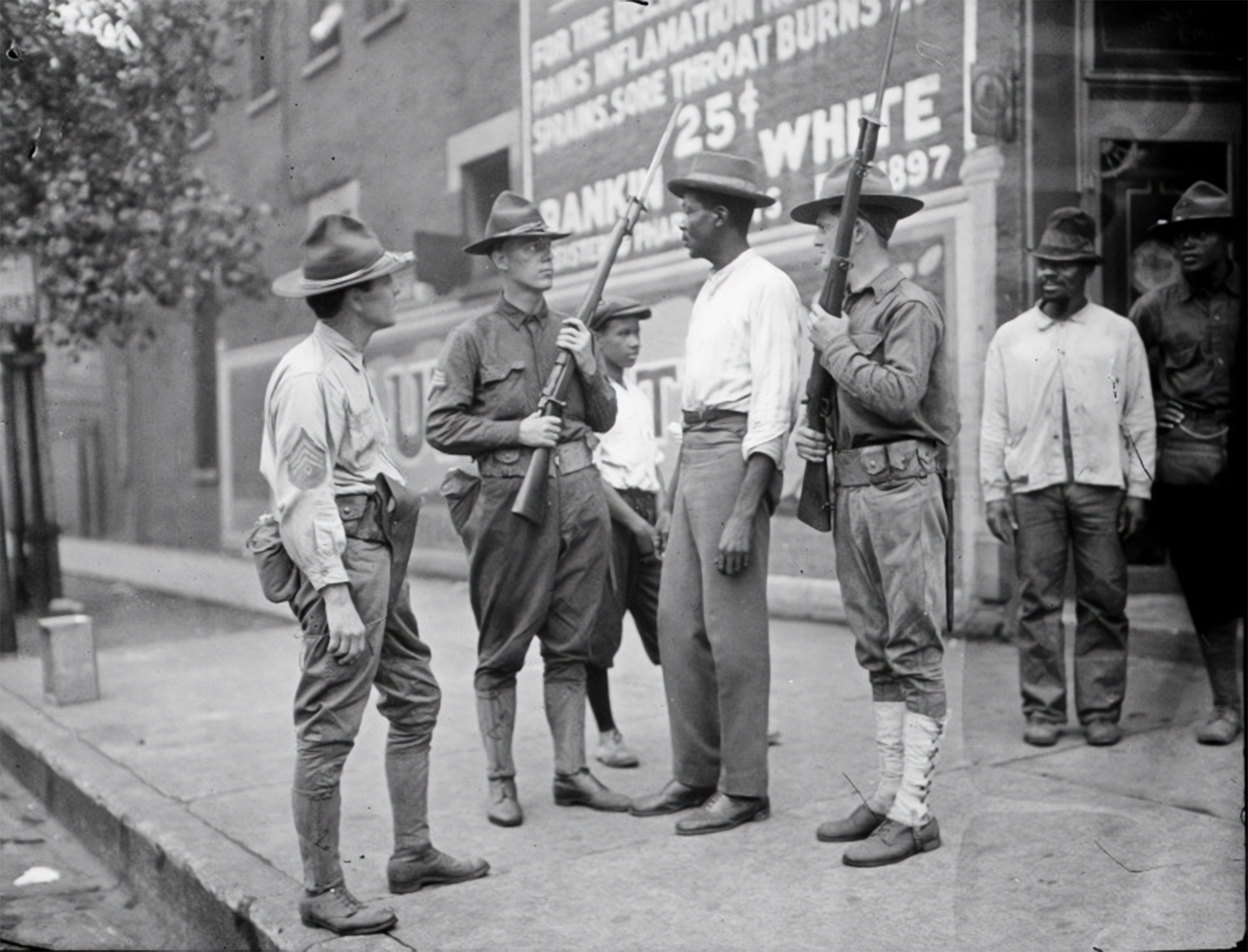

In the summer of 1919, violence broke out across America. In what became known as the Red Summer, White mobs attacked Black communities in dozens of cities and rural towns.

Black people saw their homes and businesses reduced to smoldering ruins and lost millions of hard-earned dollars. More than eighty-three Black men were lynched, in public spectacles designed to spread terror and enforce white supremacy.

Chicago saw one of the worst outbursts of violence. That summer, simmering tensions over housing, jobs, and policing ignited five days of violence—leading to the deaths of twenty-three Black residents and fifteen White residents.

Two years later in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a White mob descended on the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood. They laid waste to thirty-five square blocks, including a business district known as Black Wall Street and killed as many as 300 people.

This wave of violence exploding across the urban North and West made racism impossible to ignore. It was plain for all to see that it wasn’t solely a southern problem.

Black reformers and White allies knew they needed to dismantle segregation.

They continued to challenge racist laws and policies.

But all the while, White residents continued expanding segregation through private tools—ones that would prove much harder to fight in the courts.

What is the best way to make change?

Is protesting effective?

Is law breaking justified in fighting discrimination?

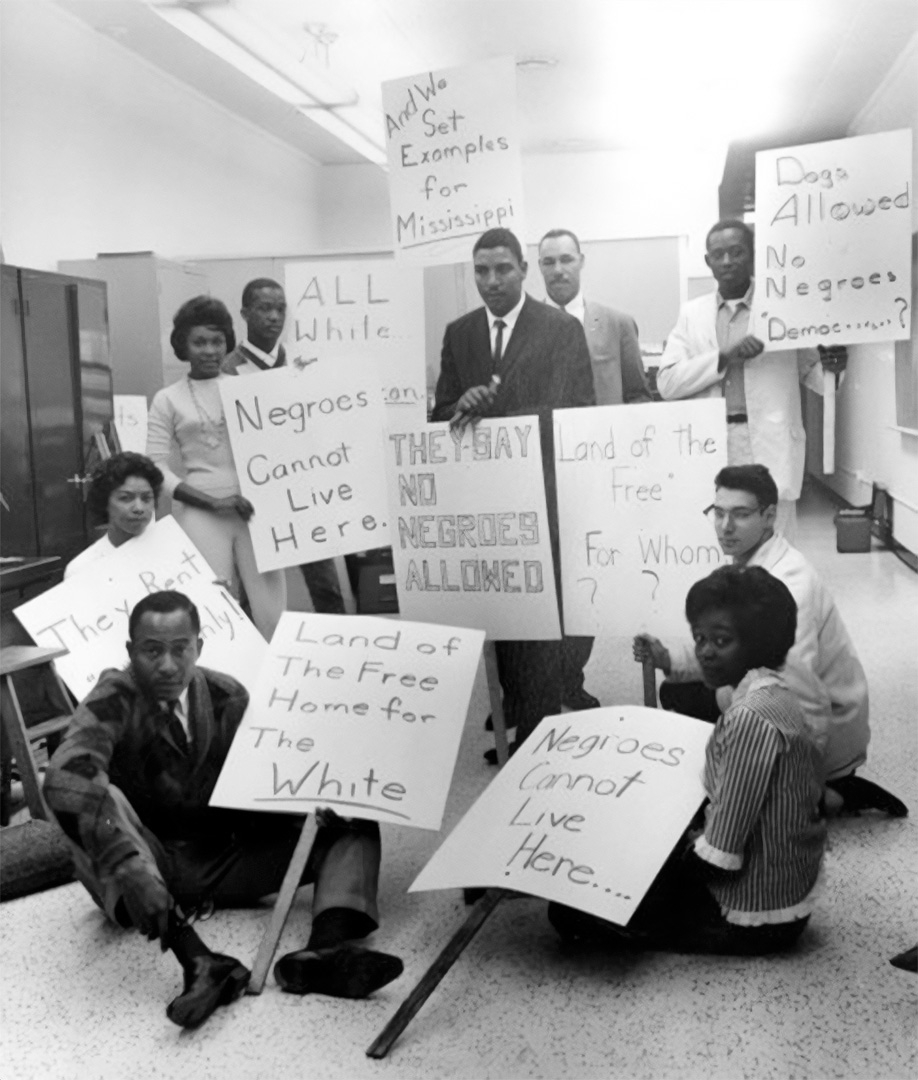

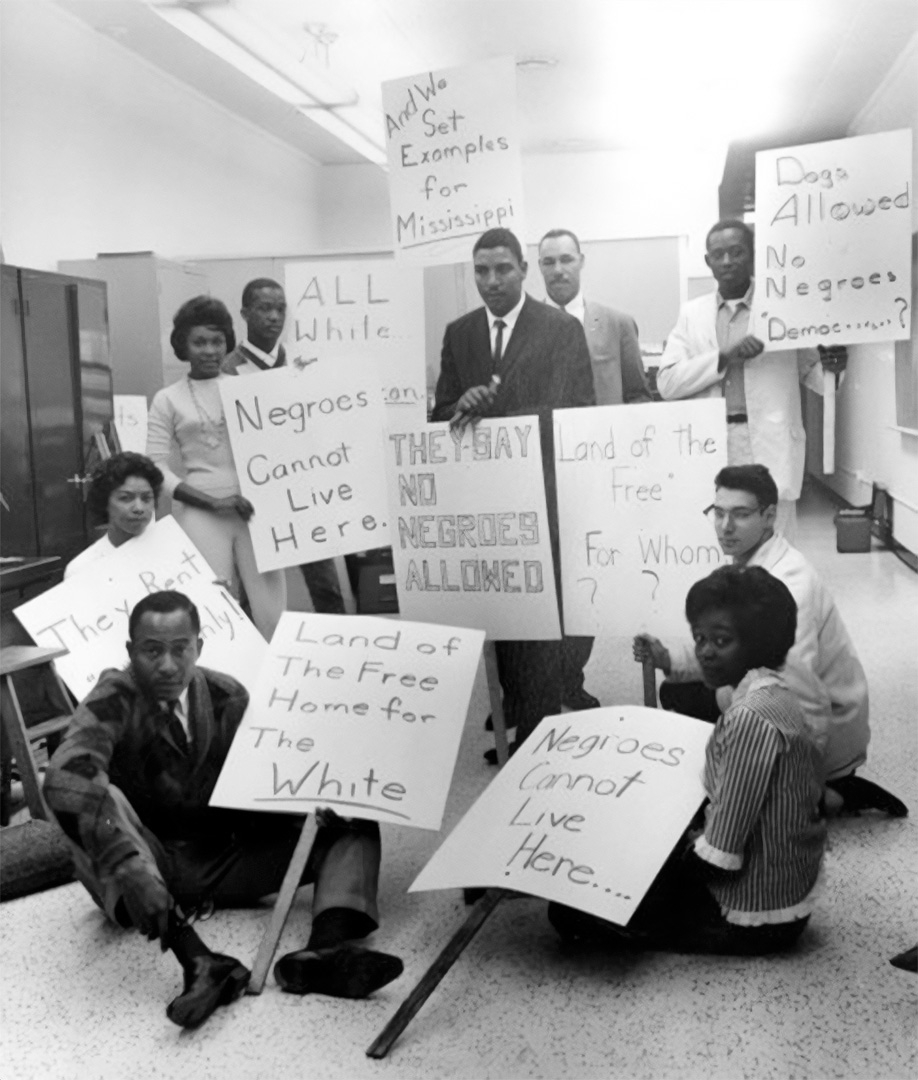

Proposition 14 was a 1964 State of California ballot initiative that would nullify the 1963 Rumford Fair Housing Act and allow property owners to openly discriminate when selling or leasing a home. It became law with 65% of voters supporting it.

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library

Resistance to racism and discrimination is part of the fabric of the American experience. Over and over, groups targeted by discrimination united to oppose housing segregation as it spread throughout the nation. Advocacy took many forms but most visibly people took to the streets as direct resistance to violence.

In the half decade preceding the Red Summer of 1919, there was tremendous upheaval in the United States.

A Black man stands in the middle of National Guard soldiers in Chicago during the 1919 Chicago Race Riot.

Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

In the half decade preceding the Red Summer of 1919, there was tremendous upheaval in the United States. Nationwide tensions grew with a world war and mass postwar demobilization, global pandemic, economic depression, a national campaign to expand suffrage to women, and a campaign to ban alcohol, known as Prohibition. These stressors accompanied rising white supremacy that exploded into violence across the country. White mobs lynched 83 Black men between April and November and started riots in Black neighborhoods in more than three dozen American cities. In cities like Chicago and Washington DC, local Black community members, including many WWI veterans, organized to defend their neighborhoods against White mobs.

As city conditions grew worse over the decades, Black activists demanded White people’s attention. During the 1960s, civil unrest broke out in Los Angeles, New York City, Detroit, Chicago, and dozens of other places across the country, causing more than 150 deaths and 20,000 arrests. White Americans often willfully misunderstood the causes of the rage.

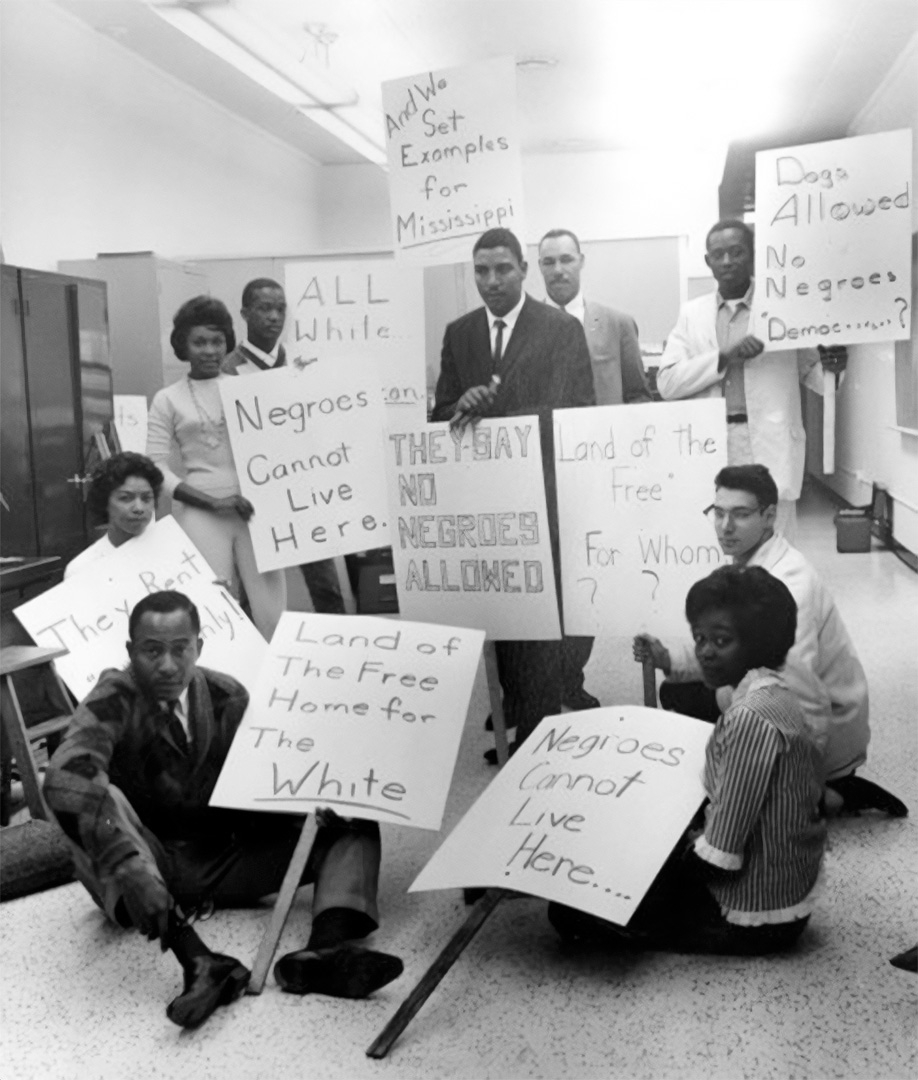

In 1962, members of the Housing Committee make signs at the Detroit Branch of the NAACP that can be used in future protests.

In 1967, President Johnson set up the Kerner Commission to analyze the causes of violent city uprisings. In its landmark report, the Commission asserted that White racism, expressed in economic disinvestment and police brutality, was to blame: “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

In 1963, on the same day that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have A Dream" speech at the March on Washington, protestors gathered at the Oklahoma State Capitol to hold a "Jim Crow funeral."

Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

The Commission recommended immediate major investment in poor and minority neighborhoods with the goal of true integration. The call was largely unheard. In polls, 58% of Black Americans agreed with the findings, but 53% of White respondents rejected the idea that racism had caused the violence.