Article 8

Shady Real Estate Practices

Courtesy of the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research

Shady Real Estate Practices

ViewHide Transcript

Public policy wasn’t the only thing that excluded Black people from desirable areas. The private real estate industry played a key role in keeping neighborhoods all-White.

In the 1910s, America’s real estate industry established national standards that promoted segregation.

Real estate agents advocated for the false belief that the presence of Black residents drives down neighborhood property values.

Starting in the 1920s, developers, brokers, and agents used a variety of tools to exclude Black families from homeownership.

We’ll start with “Steering."

Steering occurs when an agent tries to guide a homebuyer to or away from a particular neighborhood based on their race or religion. This includes agents steering White families from Black neighborhoods or agents steering Black families away from White neighborhoods.

Though outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, it remains common to this day.

Another practice is "Blockbusting."

This is where agents leverage racial prejudice to manipulate White homeowners into selling their homes at lower prices. Agents might hire a Black actress to walk around the neighborhood with a baby carriage or stage a fight between Black men to convince White homeowners to sell cheaply out of fear of neighborhood change.

Then, the agent turns around and sells the property to a minority homebuyer at a much higher cost.

Next up: “Contract Selling.”

Normally when you purchase a home, you get a mortgage loan. That way, you can buy the home now and pay it off over time.

With contract selling, a homebuyer shells out a large down payment for what’s called a “contract to deed.” The buyer pays off the loan in monthly installments but doesn’t own the home until the loan is paid in full.

In the meantime, the contract seller holds on to the deed and can evict the buyer whenever they want to, often for only minor offenses. A buyer who misses just one payment runs the risk of losing their home.

In the 1950s and ’60s, an estimated 85% of houses sold to Black families in Chicago were “contract to deed.” Contract selling robbed these families of billions of dollars.

This ruthless practice continues to this day, especially in poor and minority communities hurt by the 2008 financial crisis.

Is it ever okay to use deception to sell a house – or buy one?

How do you know when you are being fooled?

Who do you trust to help you find a home?

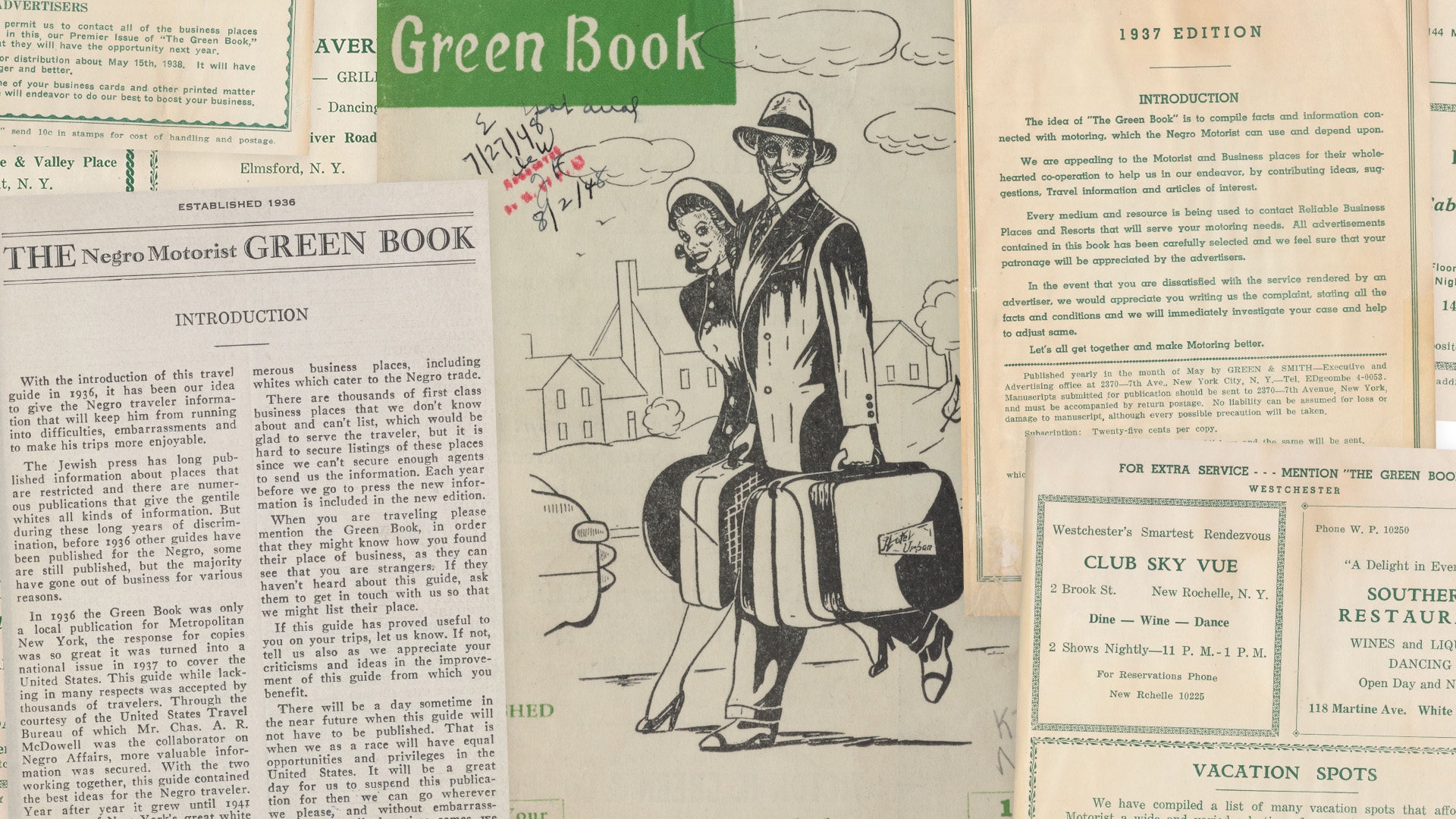

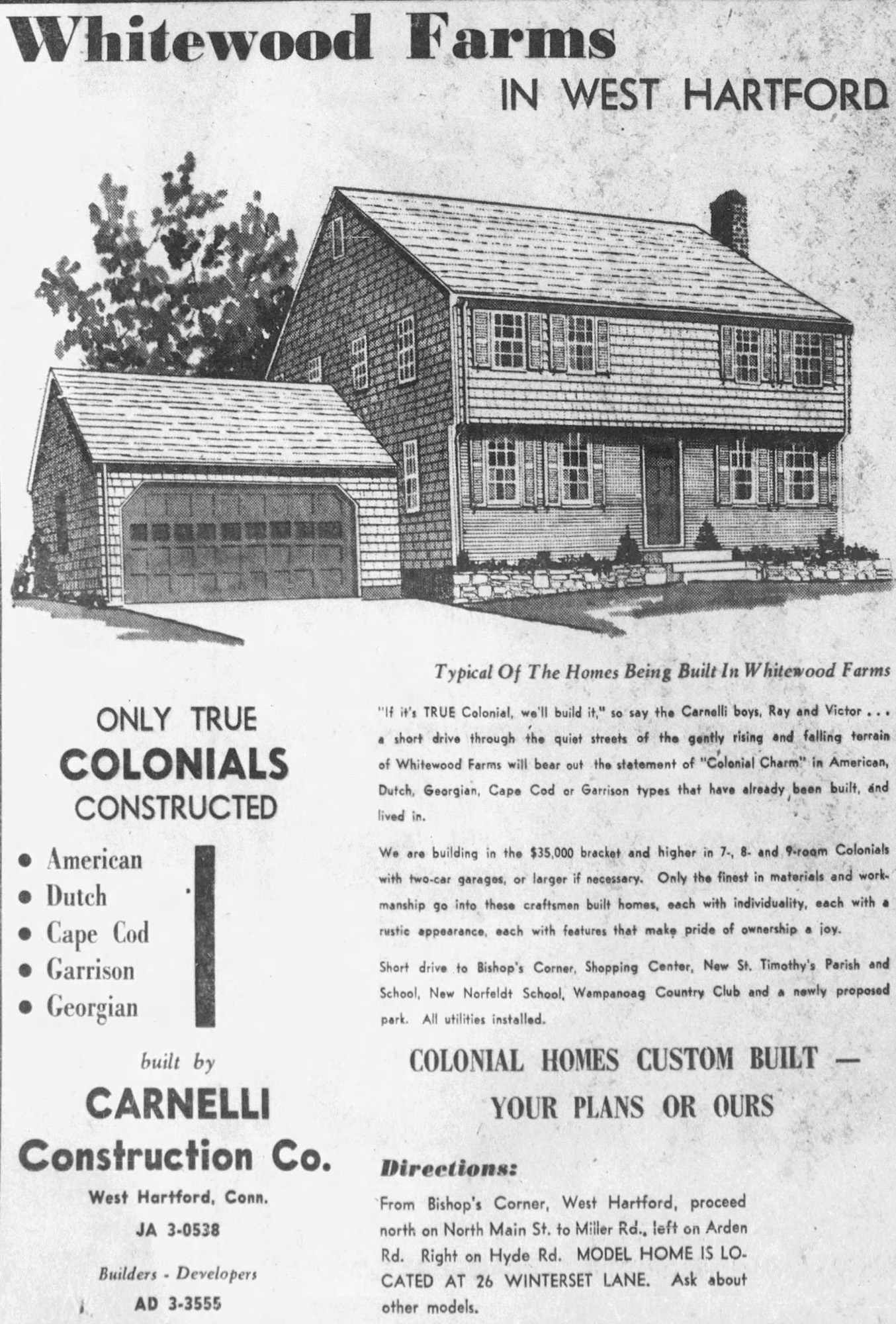

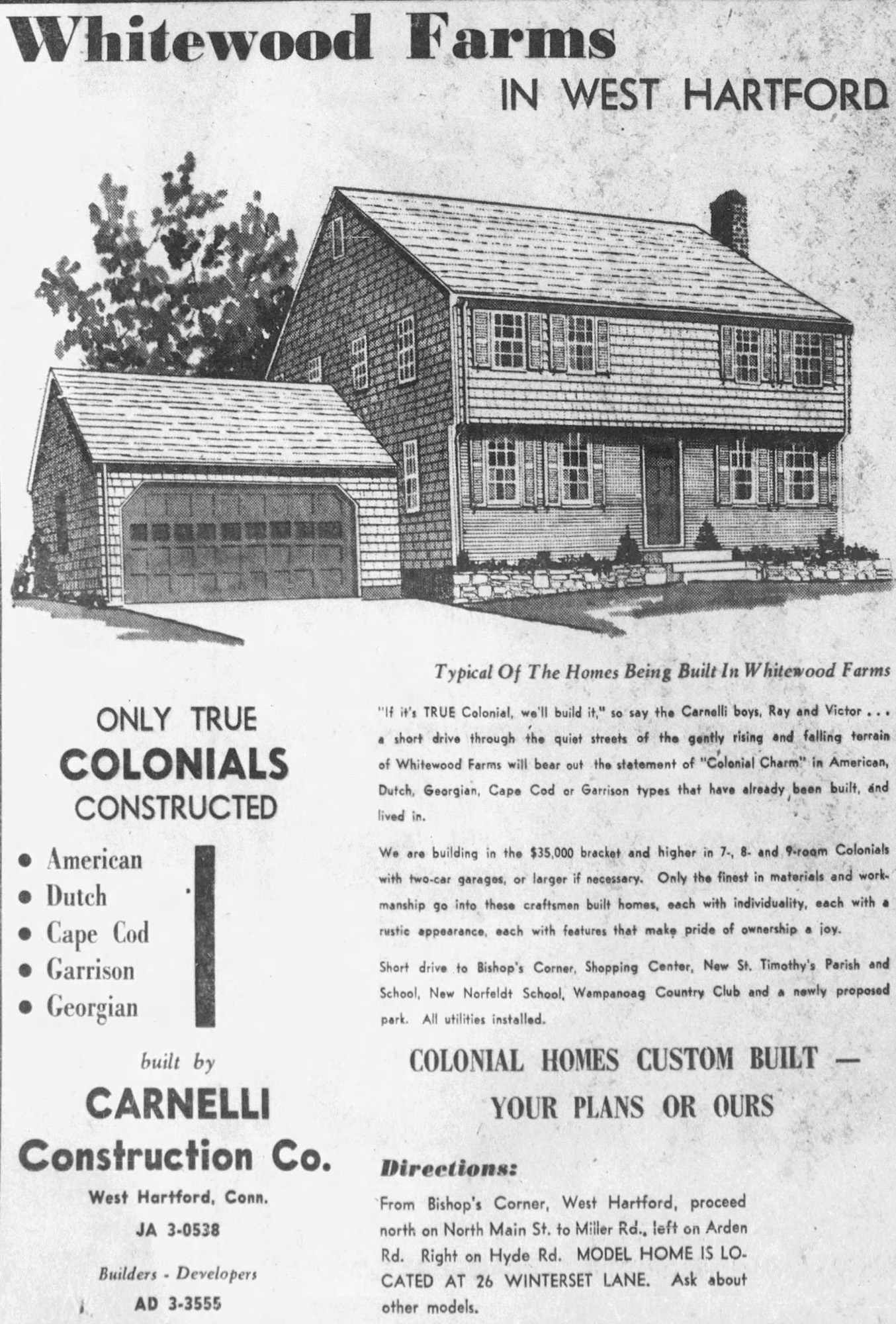

Brothers Raymond and Victor Carnelli's construction company developed hundreds of West Hartford houses between 1945 and 1970. Whitewood Farms showcases the subtlety of steering, encouraging Christian buyers to consider these homes, rather than Jewish home buyers or people of color.

© Hartford Courant. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Many families of color could afford to move to the suburbs, but often, racially biased real estate practices and unwelcoming communities stopped them from trying. After 1948 racially restrictive covenants could not be legally enforced, and people in the real estate industry developed other ways to keep neighborhoods or entire towns all-White. At the same time, they also profited from the limited choices available to Black and other minority buyers.

This sign outside of Sunkist Gardens in Los Angeles broadcast that the development was targeted to White veterans. Black veterans would be told that this was a restricted neighborhood. The picture ran in the California Eagle. Editor Charlotte Bass directed the Eagle on a campaign against housing discrimination.

Courtesy of the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research

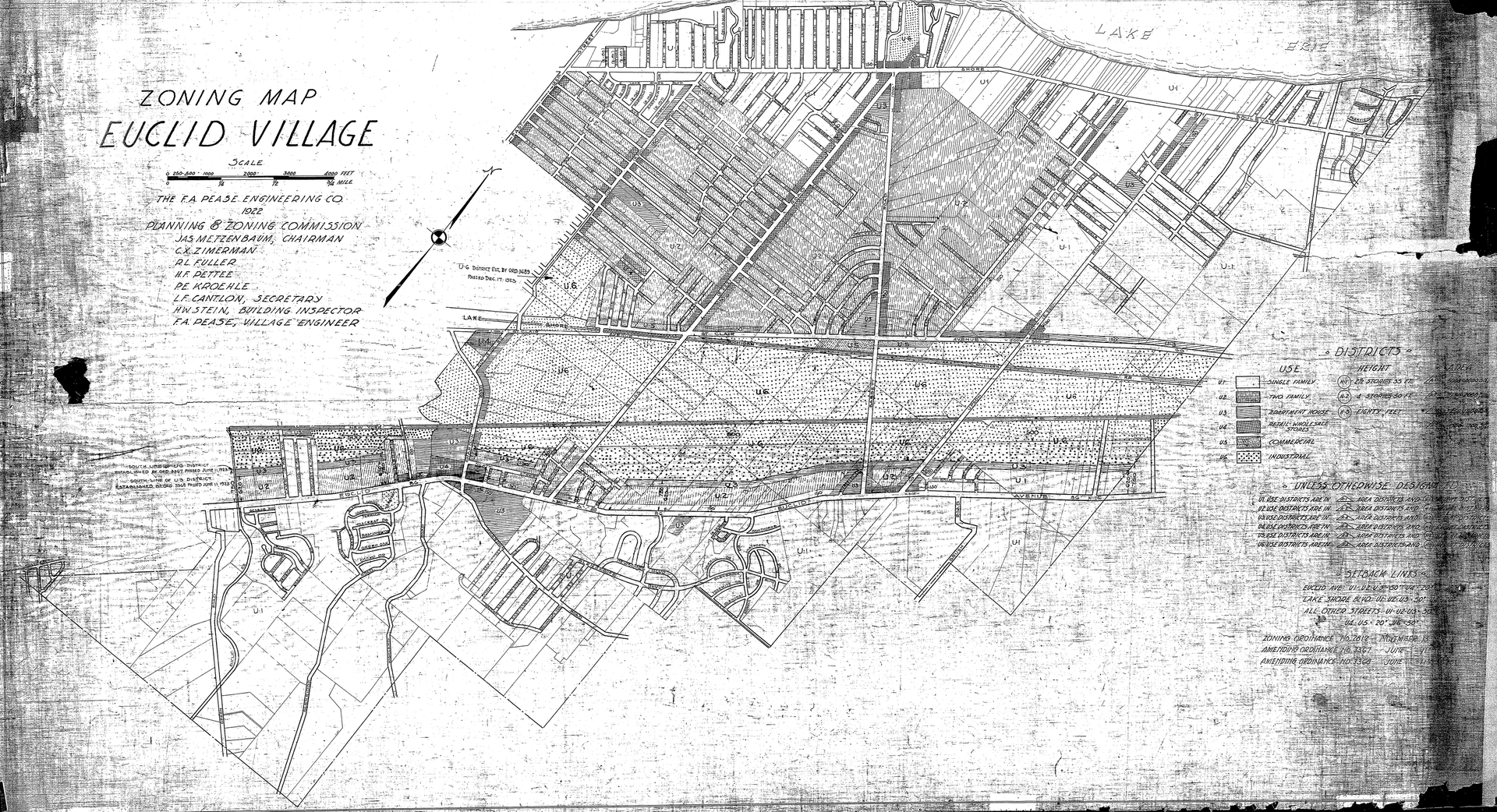

The growing housing market pushed the real estate industry to become more professional. Often seen as cheats and con men, real estate leaders needed to improve their reputations. They set up boards and standards of conduct, hoping to win back the trust of newly affluent White Americans. The real estate industry understood that success meant reinforcing racial segregation. In 1920, the Chicago Real Estate Board (CREB) voted unanimously to expel any REALTOR who sold or rented a property to a Black family on a White block. The National Association of Real Estate Brokers’ 1924 Code of Ethics prevented members from "introducing into a neighborhood...members of any race or nationality...whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values."

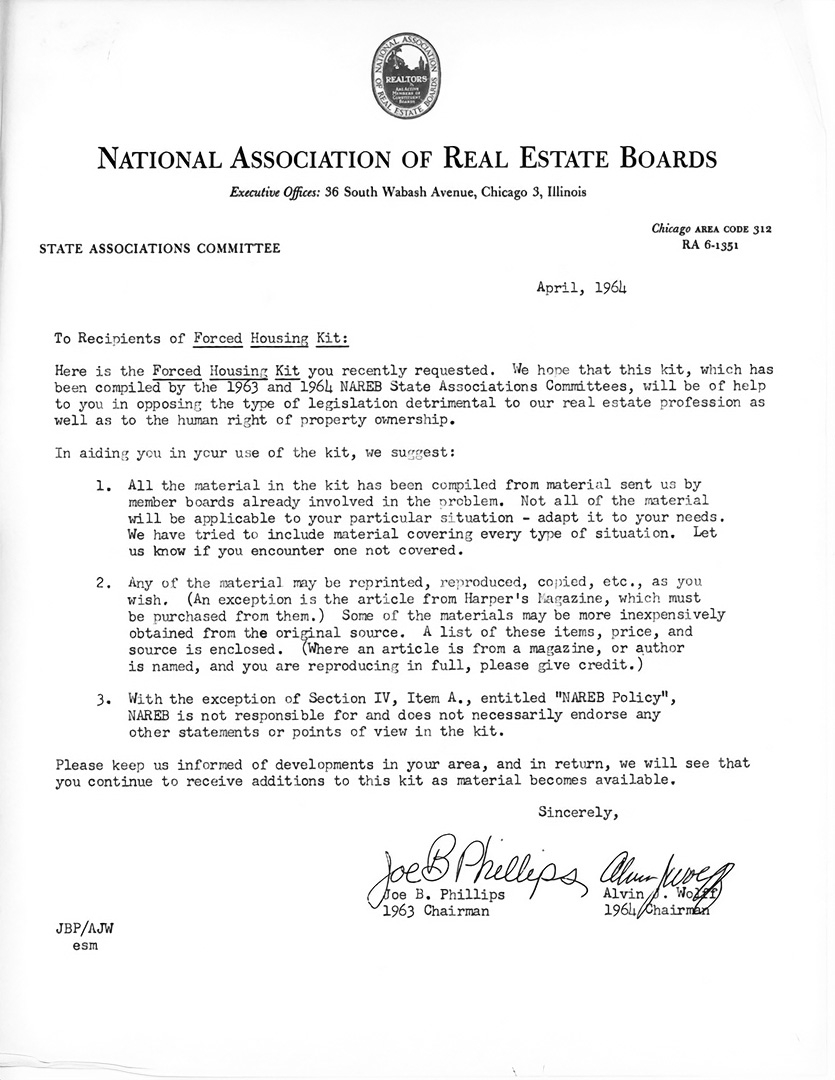

An information packet sent by the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) to help recipients fight against local fair housing legislation in the 1960s.

Courtesy of the National Association of REALTORS®

National real estate organizations honed their exclusionary practices and taught them to developers, brokers, and agents across the country. They shared the goals of maintaining segregation and winning higher returns on property sales. These were some of the techniques they used:

Steering:Steering (real estate steering): Steering is the practice by real estate agents or brokers of limiting a purchaser’s housing options based on one of the protected characteristics under the Fair Housing Act, including race, color, religion, gender, disability, familial status, or national origin. It manifests itself through one-on-one conversations, limiting access to available properties, or providing false information about a property listing. Real estate agents directed homebuyers toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their identity. Buyers would simply not be shown available houses in neighborhoods dominated by another race.

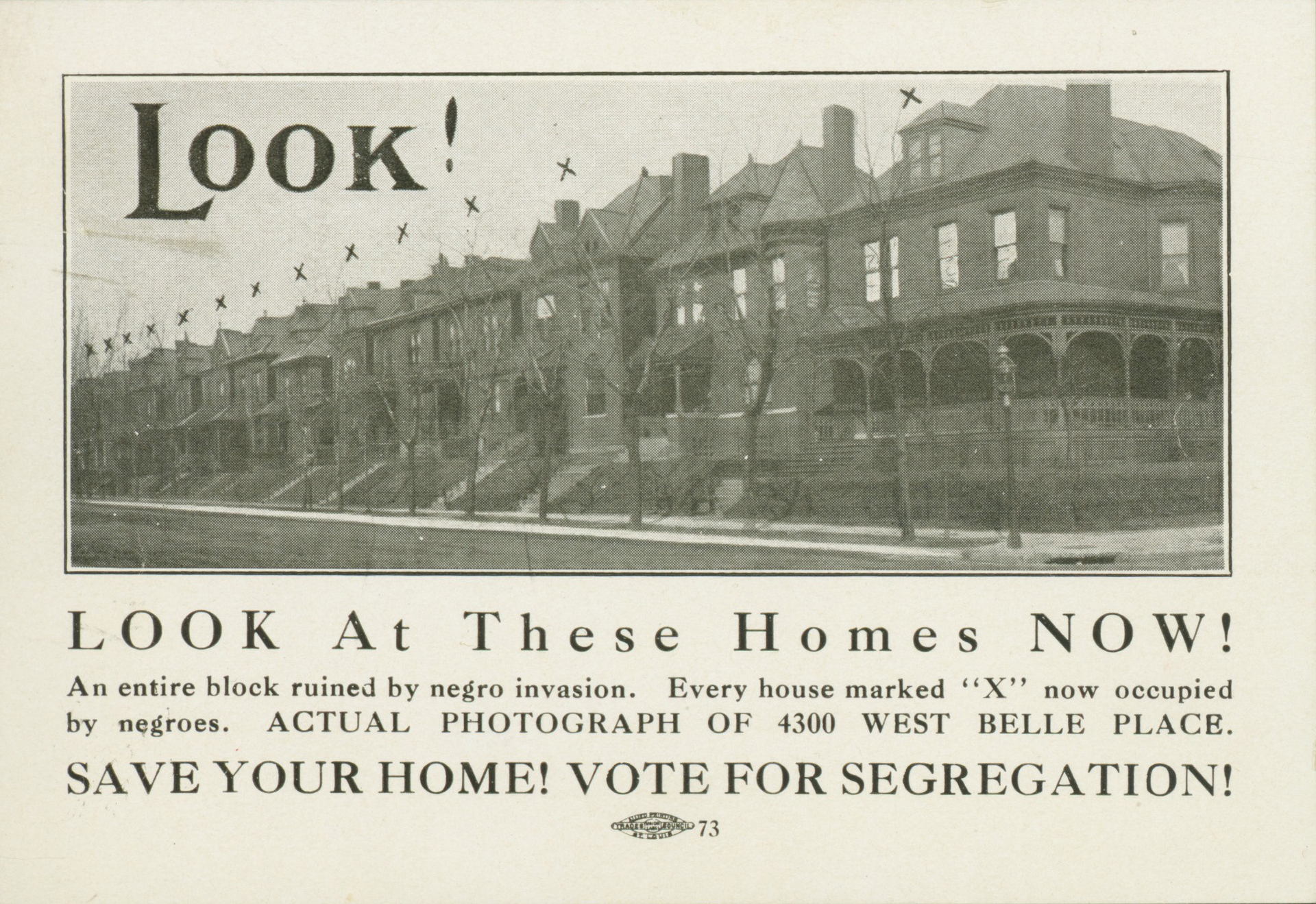

A 1916 postcard from the United Welfare Association warning of "invasion" and asking recipients to vote for segregation to save their homes.

Courtesy of the Missouri History Museum Library and Research Center

Blockbusting:Blockbusting: The act of getting homebuyers to sell their homes cheaply playing on fears of people of other races, ethnicities, or class moving into the neighborhood and then profiting from reselling the properties at inflated prices. Real estate agents and developers convinced homeowners that their neighborhood was under threat of decline from incoming people of other races and classes. Fearing the loss of home value, White homeowners agreed to sell to the real estate agent at a low price. The agent then sold the same property at a much higher price to Black or minority homebuyers. To convince homeowners that things were really changing, real estate agents might hire a Black woman to walk around with a baby carriage, or young Black men to stage fights on street corners.

Protestors block the entrance at 1235 South Keeler in Chicago on March 23, 1970. They had gathered to prevent the sheriff's office from being able to evict residents.

© Chicago Tribune, All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency.

Contract Selling:Contract selling: A practice where would-be homeowners made a deal with a contract seller for a property. The contract seller demands a high down payment and high monthly payments for buyers. The deed remained in the contract seller’s hands and buyers had no claim to it until the deed was paid in full. This allowed for abuses like sudden rises in monthly premium or evictions based on one missed payment. The contract buyer had no legal protections from abuse. This practice was targeted at Black homebuyers who were denied conventional loans based on their race. It stole billions of dollars from these would-be homeowners during the 1950s and 1960s. Rather than signing a mortgage, agents had homebuyers sign a predatory lending agreement called a “contract to deed.” Unlike a mortgage, which allows an owner to keep the equity from payments already made, under this type of contract the homebuyer owns none of the home’s value until the entire loan is repaid. Locked out of traditional mortgages, Black families often turned to this exploitive financing. When they needed to sell, people who thought they had bought a home found out they had not. Missing even one payment could mean losing the house. Sometimes, lenders demanded steep payment increases without notice. In the 1950s and 1960s, an estimated 85% of houses sold to Black families in Chicago were contract to deed, extracting between three and four billion dollars from those buyers. Contract selling still happens, particularly in poor and minority communities.