Article 2

Segregation Mania

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

What Divides Us?

ViewHide Transcript

When you hear the word “segregation,” what comes to mind?

You might be thinking of old photographs of “Whites only” water fountains and lunch counters.

But segregation was a more widespread practice than many people realize. It became entrenched in the 1890s because of deliberate government and individual actions.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, and a new era of racial segregation dawned on the United States. When a mixed-race man named Homer Plessy was arrested after refusing to sit in a “colored only” railroad car, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld segregation, establishing the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

This case opened the floodgates, and racial segregation laws spread throughout the South.

Soon, a rigid system of customs and laws known as “Jim Crow” enforced the practice of treating Black people as second-class citizens.

But segregation wasn't just a southern problem.

By 1920, formal systems of segregation affected Americans nationwide, dividing populations along racial, religious, and ethnic lines.

Opportunities for education, wealth building, and housing were reserved for White Americans and denied to people of color, religious minorities, and some immigrants.

And while segregation was a national policy, it was carried out by people and institutions at the local level.

For many Americans, who you were limited where you could live. In places like Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles, Black newcomers from the South were isolated in inner-city ghettos and slums. In the Southwest, Latino residents were segregated into urban barrios. And on the West Coast and in major cities across America, people of Asian descent were hemmed into segregated Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and Little Manilas.

Residential segregation was enforced on the books and in the streets, with restrictive covenants and white violence dividing neighborhoods by race.

As the twentieth century wore on, segregation hardened across the country, becoming a pervasive aspect of American life, and limiting the progress of millions of Americans.

What makes you feel welcome in a community?

What makes you feel unwelcome?

What makes people move from one place to another?

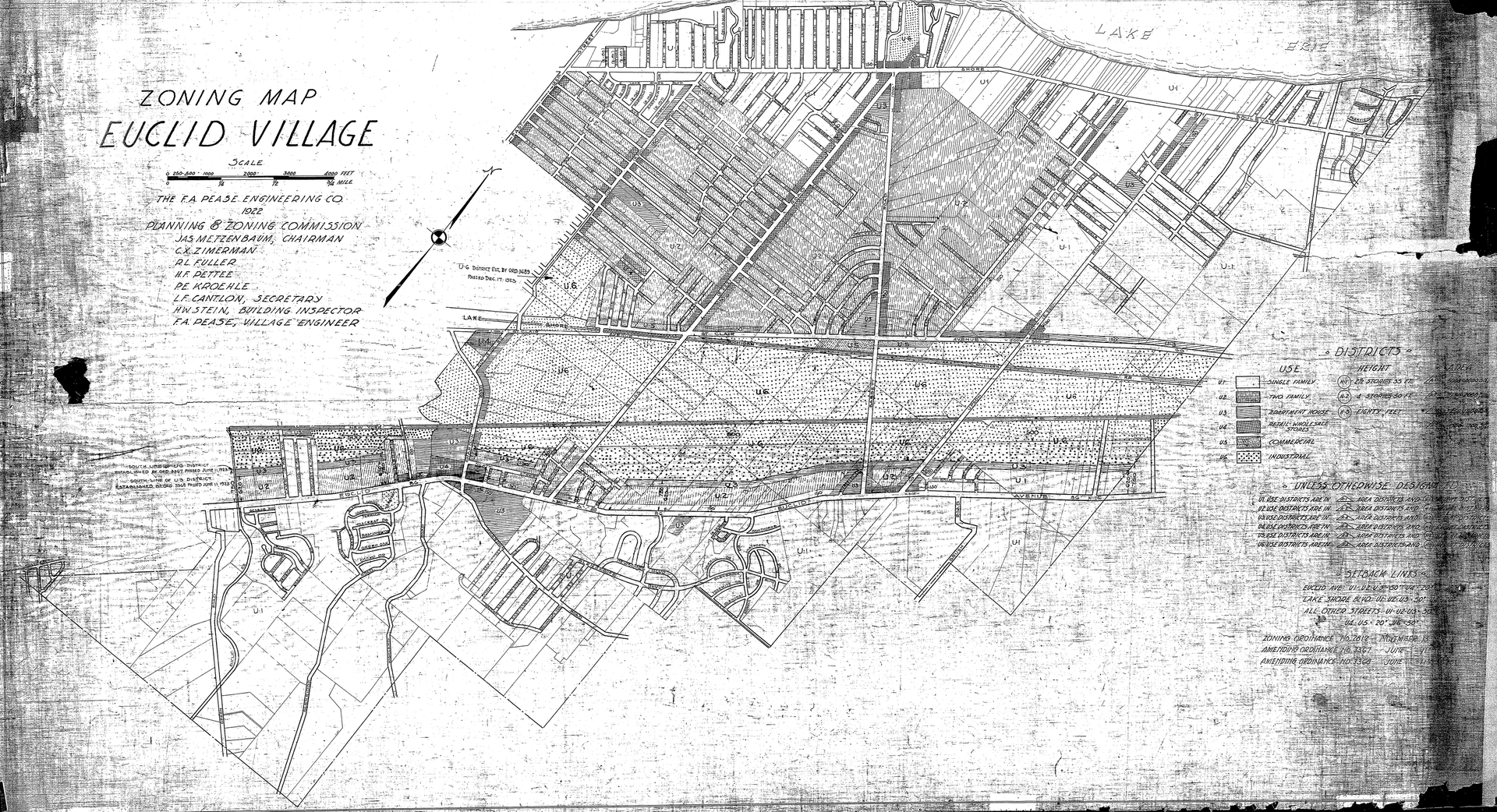

Segregation reached far beyond the American South. Beginning around 1890, America as a whole became an intentionally segregatedSegregation: The act of separating people based on race, class, or ethnicity enforced through legal means or customary practice. nation. The effort was so intense that historian Carl H. Nightingale calls it a time of “segregation mania.”

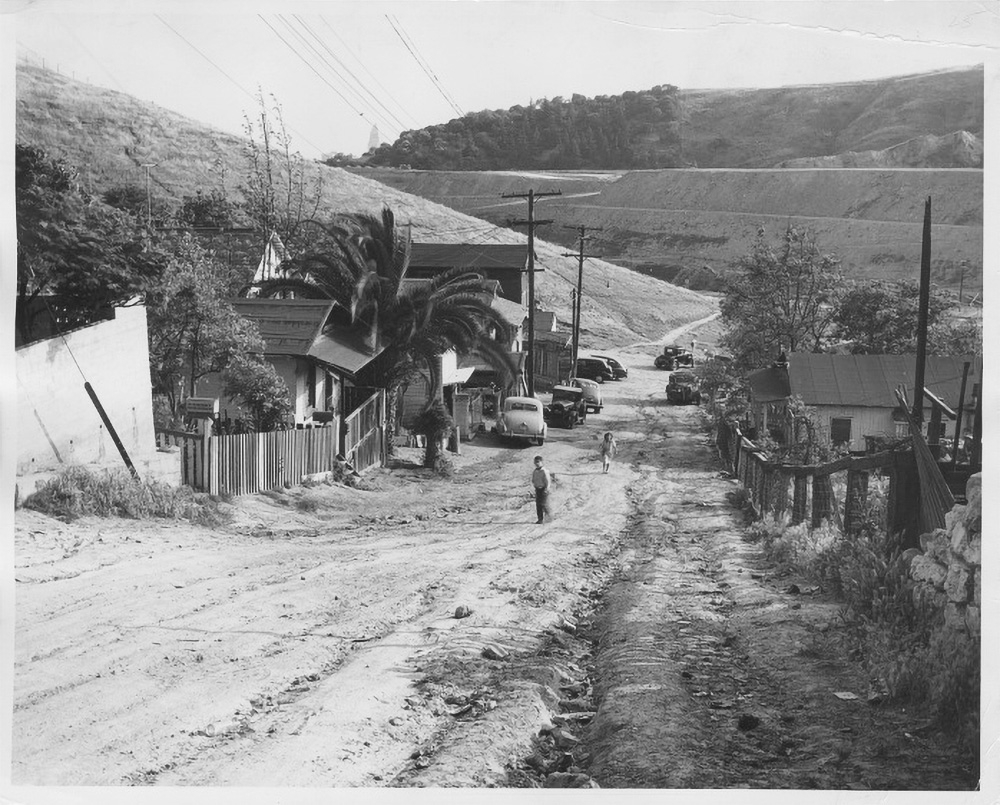

View of a street in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, California in 1942.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Communities were changing fast, and people in power wanted to control that change. At local, state, and national levels, affluent White Americans used new tactics to divide people along racial, ethnic, religious, and class lines.

The exclusion of people from places is probably one of the most salient experiences that has touched every single community globally and across time.

Scholar and Writer

ViewHide Transcript

I mean, displacement is, in the exclusion of people from places, is probably one of the most salient experiences that has touched every single community globally and across time. I'm a slavery scholar, so I've actually been studying the specifics of that type of displacement. What it means to have captured and removed someone from one place and moved them into another space. And all of the violence of that. And it's really thousands of years old, I think, you know, it gave. It was given rise, at least in recorded history, to the rise of cities and in agricultural practices, interestingly enough. But, I mean, people being moved or excluded from spaces displaced from spaces. All you need to do is study that subject and you will study the creation of nations, the creation of neighborhoods, the creation of cities and it's an old, old story. But it's also one of the—it's a new story. As we think about legislatures who have been thinking about census this past year and really grappling with, you know, how they divide political spaces up. It's such a salient experience that has defined so many communities and been experienced by so many communities.

Immigration helped to spark the mania.

Immigrants waiting at Ellis Island.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Immigration helped to spark the mania. Fast-growing industries in northern and western cities demanded an immense workforce. Immigrants, mostly from Europe, supplied much of the needed labor. Alongside them came internal migrants, including Black Americans and working-class Whites, moving from rural parts of the United States. Thronging into cities, new arrivals found themselves living in close quarters with one another. Racial and ethnic groups mixed, mingled, and sometimes clashed. White Americans worried about how all these changes might impact their own power and wealth. Using pseudoscientific ideas made popular at the time about racial hierarchies, they created policies that dictated where newly arriving people were allowed to live. Because these ideas were presented by influential scholars, they gained mainstream acceptance. All of these theories on racial hierarchies have since been discredited.

Anti-Black racism also drove segregation. After the Civil War, free Black Americans moved out of the South in vast numbers. All over the country, they tested Constitutional promises of freedom, only to find that many White people refused to honor those ideals. Racial separation became the norm, soon hardening into systematic legal segregation. Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man from New Orleans, challenged the legality of separate railroad cars by trying to ride in a Whites-only car. He took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court and lost. The Plessy v. FergusonPlessy v. Ferguson, 1896: A US Supreme Court decision which upheld the legality of Jim Crow laws by contending that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. This ushered in a period of legalized racial segregation in the United States that remained in effect for over fifty years until it was overturned by Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. decision stated that “separate but equal” facilities were allowed under the Constitution. Segregation was now the law of the land.

Resource

Historian Yohuru Williams explains Plessy v. Ferguson and its impact.

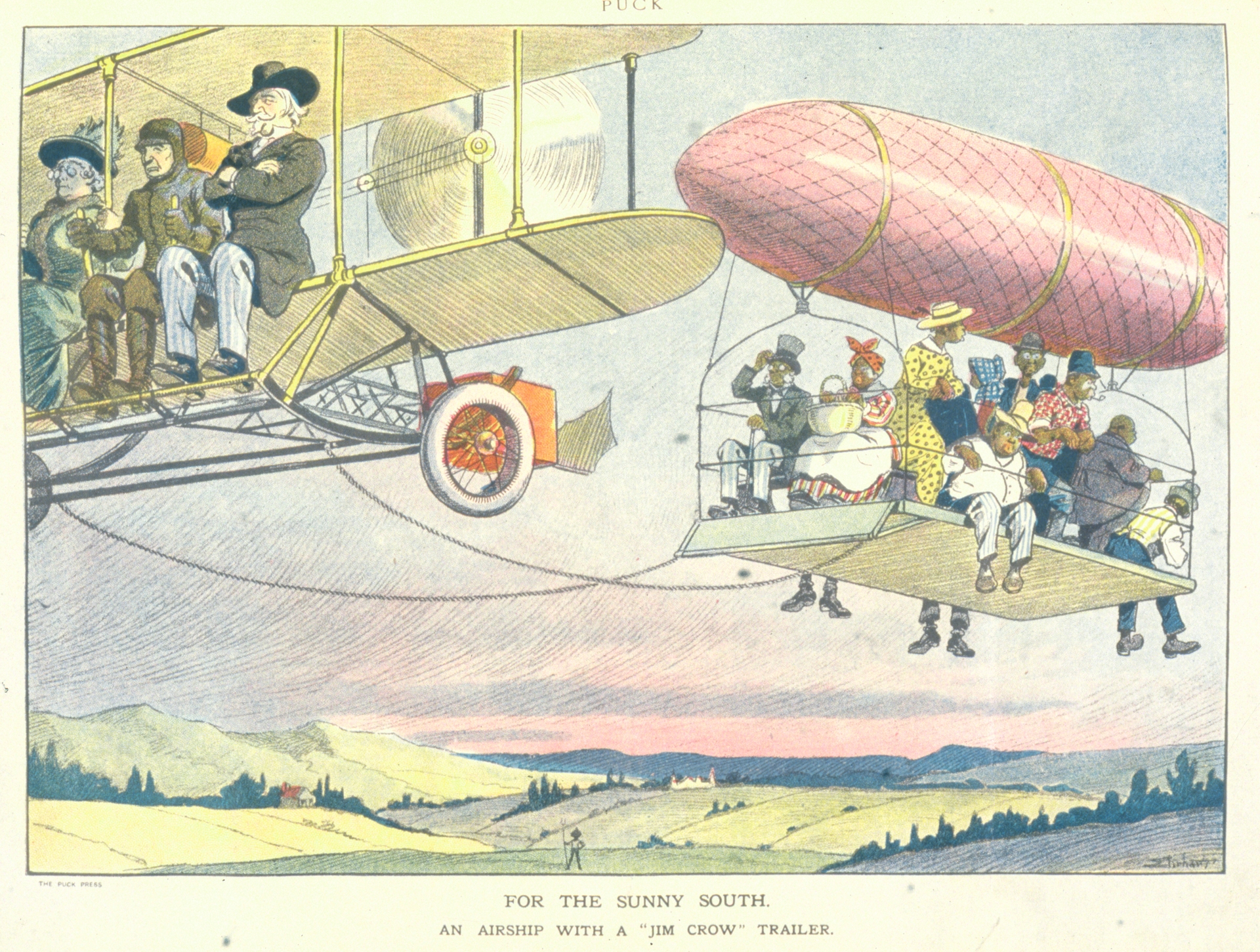

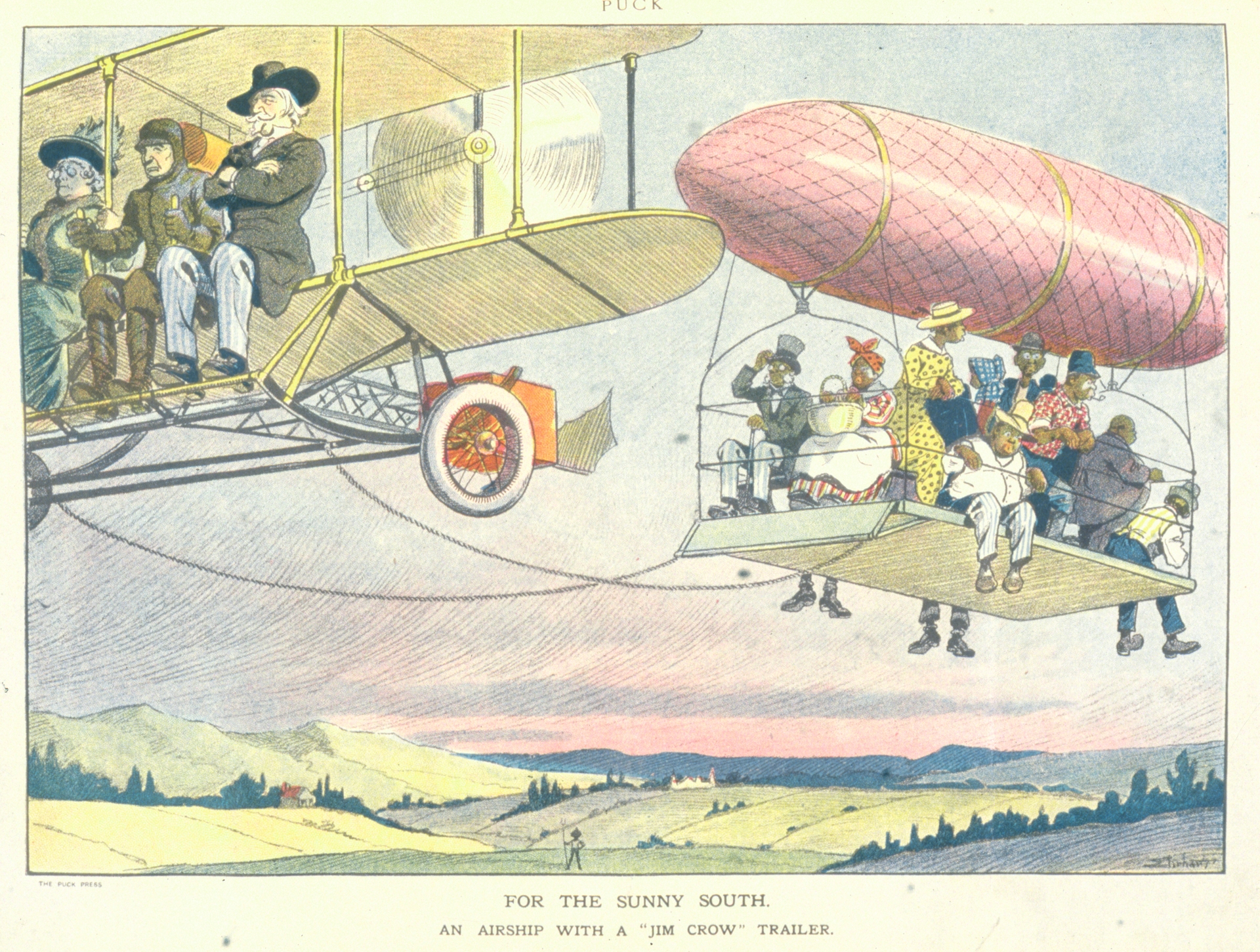

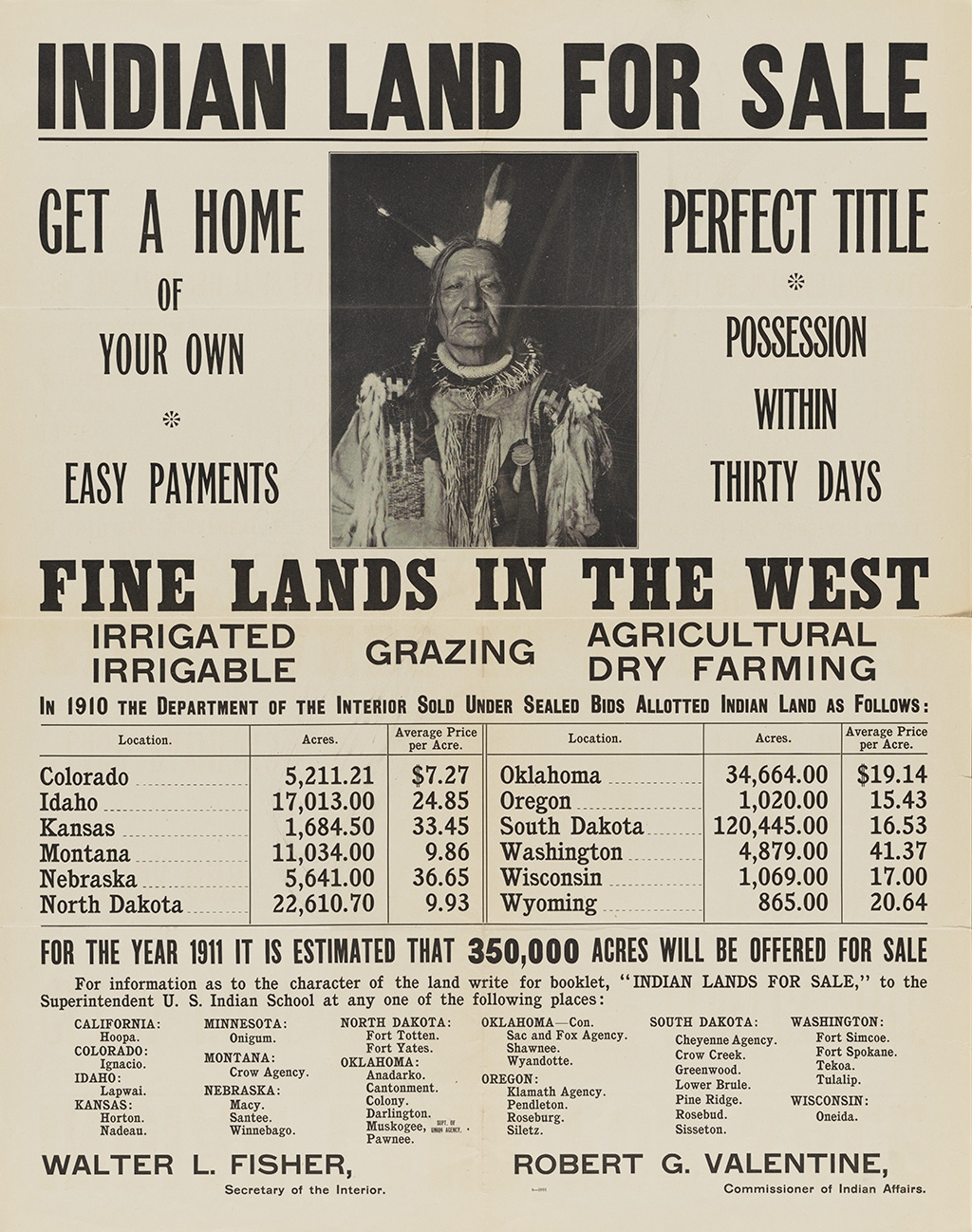

A caricature of the Jim Crow system that shows White people in a plane with Black Americans being pulled on a blimp.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In the South, the federal approval of segregation supported the Jim CrowJim Crow: A system of social customs and restrictive laws that controlled every aspect of life for Black Americans. regime, a system of social customs and restrictive laws that controlled every aspect of life for Black Americans. A new landscape took shape, with two of everything: Black and White people had separate restrooms, water fountains, libraries, textbooks, schools, theater seats, train and bus seats, waiting rooms, hospitals, jails and prisons, restaurants, bars, and shops. In the Jim Crow years, White people across America policed the behavior and movement of people of color using laws, intimidation, and often, violence.

Invisible boundaries were drawn around neighborhoods. Northern cities like Chicago funneled Black migrants into tightly packed neighborhoods or sent them to makeshift housing on city outskirts. In southern cities like Atlanta and Richmond, Black residents were gradually pushed into segregated blocks and prevented from moving elsewhere by local ordinances.Ordinances: An ordinance is legislation enacted by a municipal governing body. Ordinances allow for standardization of city life including property zoning and annexation, alcohol regulation, and public health regulations. They can also serve discriminatory ends through sundown ordinances, vagrancy ordinances, and other ordinances targeted at members of specific groups. Even in places without these laws, Black people often settled together as a survival strategy, building community, culture, and institutions outside of White control.

Two children in Chavez Ravine. This site was selected for the Elysian Park public housing development, which was never built, and ultimately became Dodgers Stadium in 1962.

Courtesy of the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research

In different parts of the country, housing discrimination created other segregated neighborhoods. Barrios, or neighborhoods of Spanish-speaking people, emerged in southwestern cities like El Paso and Los Angeles. Some lived in colonias, or informal immigrant settlements in areas at the fringes of cities near the U.S.-Mexican border. Many Mexican Americans, the largest proportion of barrio residents, had not immigrated into the United States. Instead, the nation’s borders shifted underneath them after the Mexican-American War ended in 1848. Families had lived in those places for centuries before the American states existed.

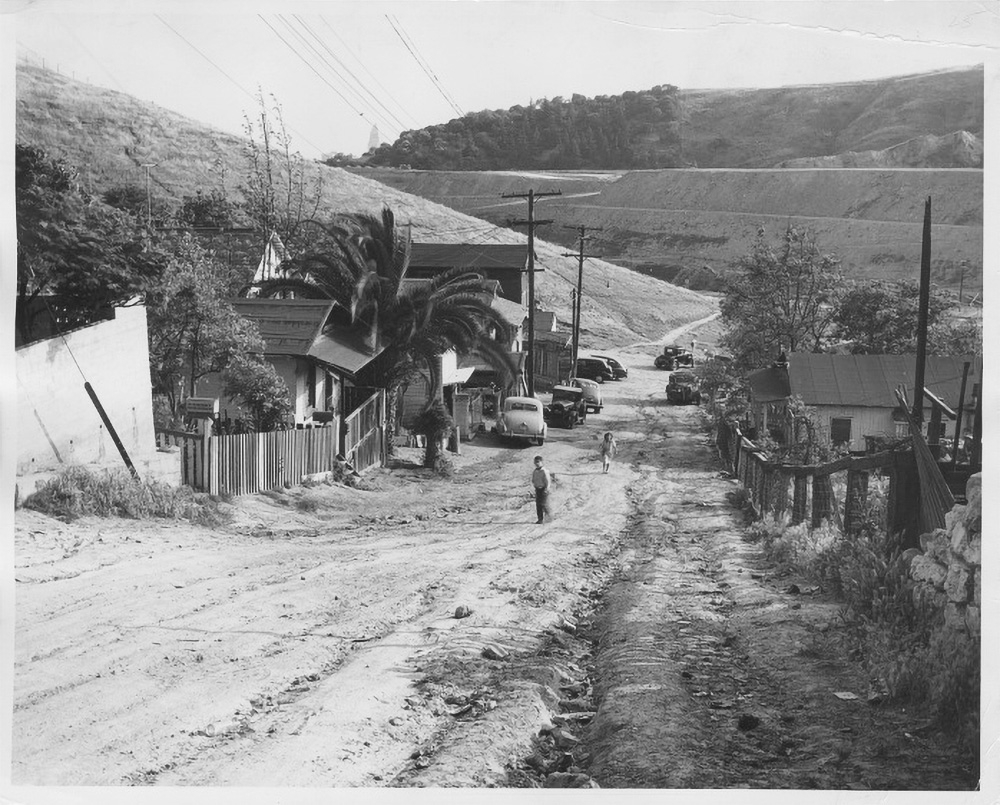

A color-coded map of San Francisco's Chinatown produced by the San Francisco Daily Report in 1885.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

On the West Coast, people of Chinese and Japanese ancestry also faced residential segregation. First-generation Asian immigrants were non-citizens due to restrictions set by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882: A Congressional Act that barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States. It effectively ended Chinese immigration until 1943. White violence and nativistNativism: The policy of protecting and promoting the interests of native-born inhabitants of an area over immigrants. intolerance often kept people of Asian descent hemmed into segregated Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and Little Manilas. Prohibited from buying properties in White neighborhoods because of fears that they were criminal or vicious, people of Asian descent were restricted to these ethnic neighborhoods.

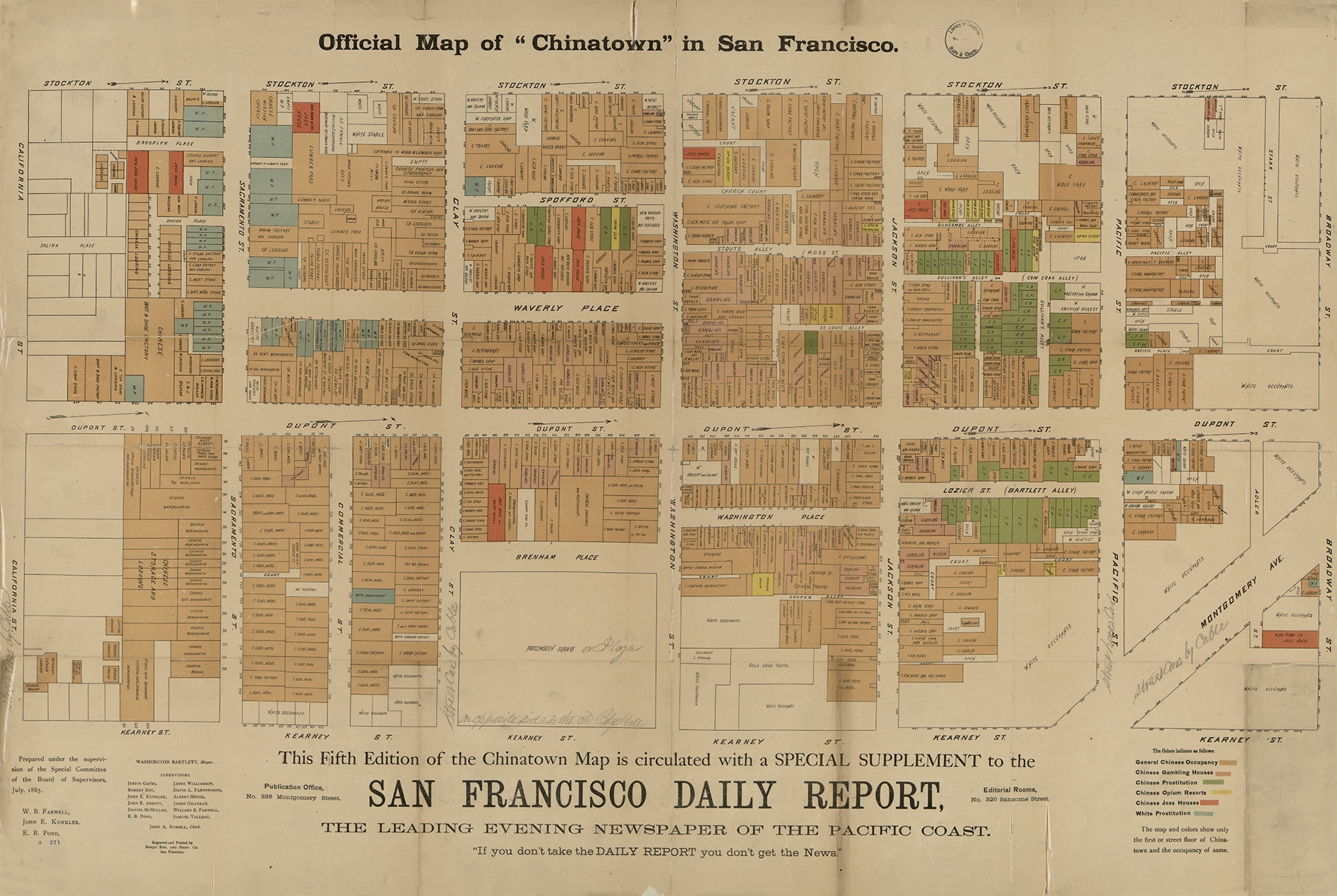

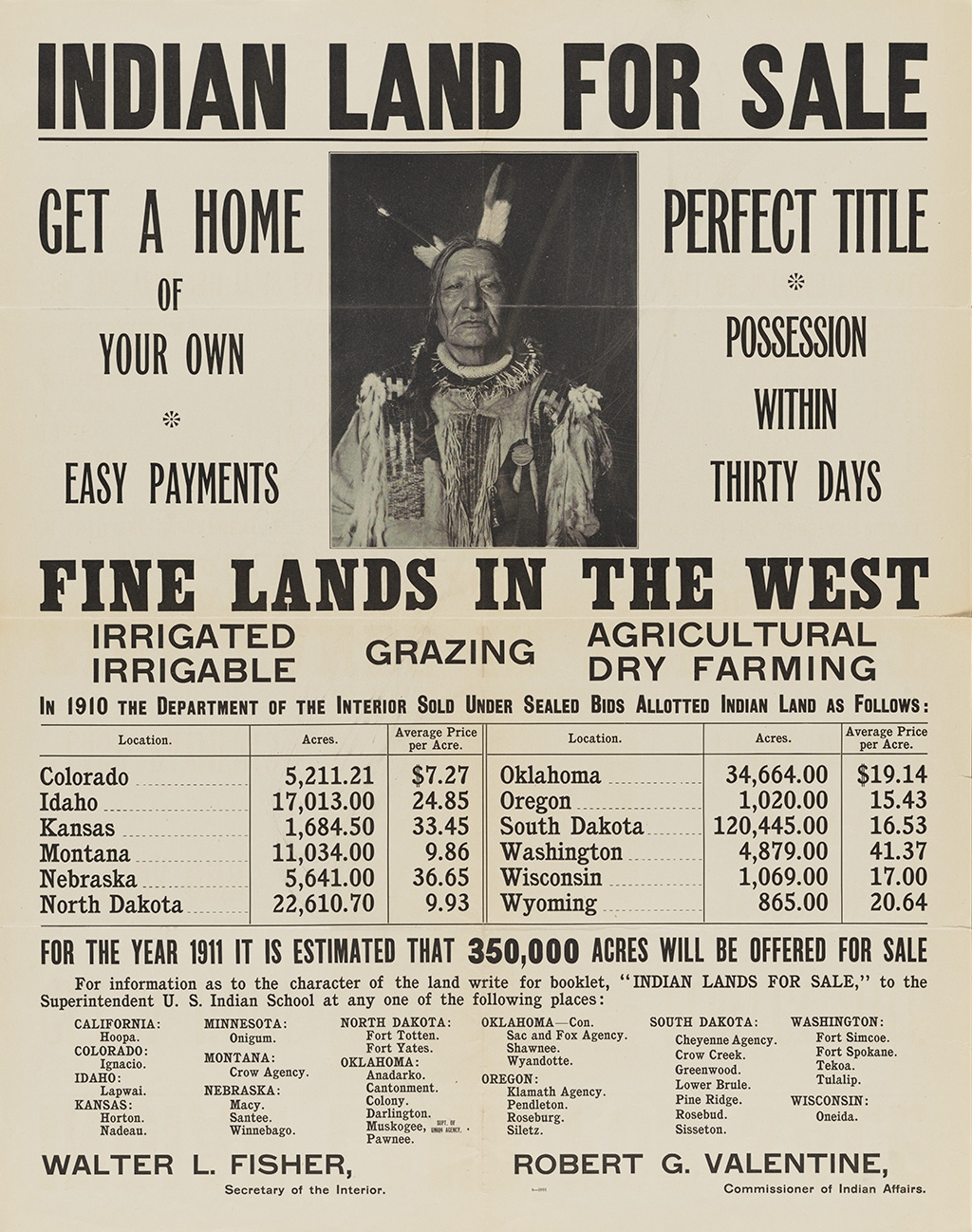

Print advertising land for sale by the United States Department of the Interior in 1911.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Indigenous people’s freedom to move was also controlled by the United States government. In the 1880s, the government began trying to dissolve reservations,Reservations: A predominantly mid-to-late nineteenth century US government solution for containing, confining, separating, and restricting Indigenous populations onto federally reserved land plots with strictly defined borders. Indigenous people who had already been forcibly removed from ancestral homelands in the eastern part of the US were now seen as hinderances to westward American expansion. This era brought a renewed interest in the US government to push American civilization onto Indigenous people, but this time Indigenous children were targeted. A system of industrial boarding schools was established, and Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families and subjected to a harsh and traumatizing program designed to completely erase their cultural identities and heritage. which were becoming centers of Indigenous political power. Many Native youth were taken from their homes and sent to Western-style boarding schools that aimed to erase their cultural identities. The 1887 Dawes ActDawes Act of Dawes General Allotment Act, 1887 : A Congressional Act that broke up Indigenous reservations into individually owned farms, destroying traditions of shared land use. Excess land was sold to non-Indigenous buyers for farming, ranching, and mining. The federal government took over one hundred million acres of land from Native nations that has yet to be recovered. During the Allotment era, government agents created tribal membership rolls that identified Indigenous people’s blood quantum (the perceived amount of Indigenous blood an individual contained) and officially registered members of each federally recognized Native nation. If an Indigenous person was not present when the rolls for their community were established, they could be denied tribal recognition and benefits. Allotment tribal membership rolls continue to impact Indigenous communities because they are often used to determine contemporary tribal status, affiliation, and access to benefits from the federal government. broke up many reservations into individually owned farms, destroying traditions of shared land use and often leaving families with dry, hard-to-farm land. Excess land was sold to non-Native buyers for farming, ranching, and mining. The federal government took over 90 million acres of land from Native nations that has yet to be recovered.

W. E. B. Du Bois' albums of photographs showing Black life in Georgia were displayed at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

By 1920, across America, the most desirable homes and neighborhoods were set aside for White people. People in power used laws, social customs, harassment, and violence to exclude people of color, religious minorities, and immigrants whom they believed to belong to “lesser” White races (such as Italian, Irish, Jewish, and Polish people). Segregation was built into American cities and carried out by local people working in banks, real estate offices, police stations, courts, and municipal buildings. The choice of where to live, rather than free and personal, was now being set in stone and brick. This system of division and discrimination closed off opportunities for education, wealth building, and employment. Many White Americans accepted segregation as a permanent and natural condition, deeply impacting how people understood race and class for the next century.

Additional Resources

Historian Yohuru Williams explains Plessy v. Ferguson and its impact.