Local Spotlight

Oak Park, Illinois

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

Community Profile

- Community: Oak Park, 1835

- County: Cook

- State: IL

- Type: Suburb

- Metro: Chicago

Located ten miles west of Chicago’s Loop, the 4.7-square-miles comprising Oak Park were most recently homelands to the Potawatomi people. In 1833, the Treaty of Chicago forcibly removed Indigenous people from Illinois and further enabled investors and residents to establish White settlements. By the 1880s, a small number of Black residents were recorded in historic sources. In 1905, 100 Black residents built the Mt. Carmel Baptist Church. Despite this history, Oak Park’s Black population did not exceed 1% of the total population until 1980. The growth of Oak Park’s Black community was spurred by grassroots organizing and public policy to build a racially integrated community. Today, a socioeconomically, racially, and religiously diverse range of people call Oak Park home, including a visible LGBTQIA+ community and sizable Black, Jewish, Asian, and Latino populations.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 59.5%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $387,300

- Median Gross Rent: $1,175

- Median Income: $94,646

- Poverty Level: 7.7%

- High School (ages 25+): 96.5%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 70%

Exclusion and Resistance in a Twilight Town

As Oak Park, IL became a nineteenth-century bedroom suburb on Chicago’s western periphery, it developed a distinct cultural identity featuring numerous mainline Protestant churches, a staunch commitment to temperance, high-quality public schools, and notable architecture. In 1902 Oak Park incorporated as an independent village, warding off annexation by Chicago. Black people, Catholics, Jews, and newer immigrants were constrained and limited to only some of the community’s economic and social opportunities creating a twilight existence of ambiguous and contested status.

Mt. Carmel Baptist Church opened in 1905. It was located just south of Oak Park’s main business district in the area that had the highest Black population. A few years earlier, White residents had blocked efforts to build the church in northeast Oak Park in an area of new middle-class homes.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

From its beginning, Black Americans lived and worked in what is now Oak Park. Black children attended and graduated from integrated local schools. Black individuals and families bought and rented property and established businesses. By 1887, a small group of Black Christians came together weekly to worship and build a community, renting space to gather and eventually coalescing into Oak Park’s first Black congregation, Mt. Carmel Baptist Church. As the congregation grew some local White ministers and community leaders verbally and financially supported the congregation as it planned for its own building—but that support was not universal and had limits.

When the church purchased a plot of land outside the largest black enclave, White resistance led the village to rescind its building permit in 1904, forcing Mt. Carmel to build in the Black neighborhood the next year, adjacent to the central business district. The church and its building became the cornerstone of community life for the area’s Black residents. Mt. Carmel’s church-building travails demonstrated the constraints on minority rights in Oak Park. When Oak Park’s Catholics broke ground for their first church two years after Mt. Carmel opened, a White Protestant straw buyerStraw buyer: Prior to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, non-White buyers were often denied access to purchase homes in their preferred neighborhoods. To sidestep this exclusionary practice, minority homebuyers arranged for White friends or sympathetic volunteers to purchase homes using their money and then the property’s deed would immediately be transferred to the minority buyer. This was an effective method for skirting discriminatory housing practices. purchased land for the parish because of anti-Catholic sentiment among the White Protestant majority.

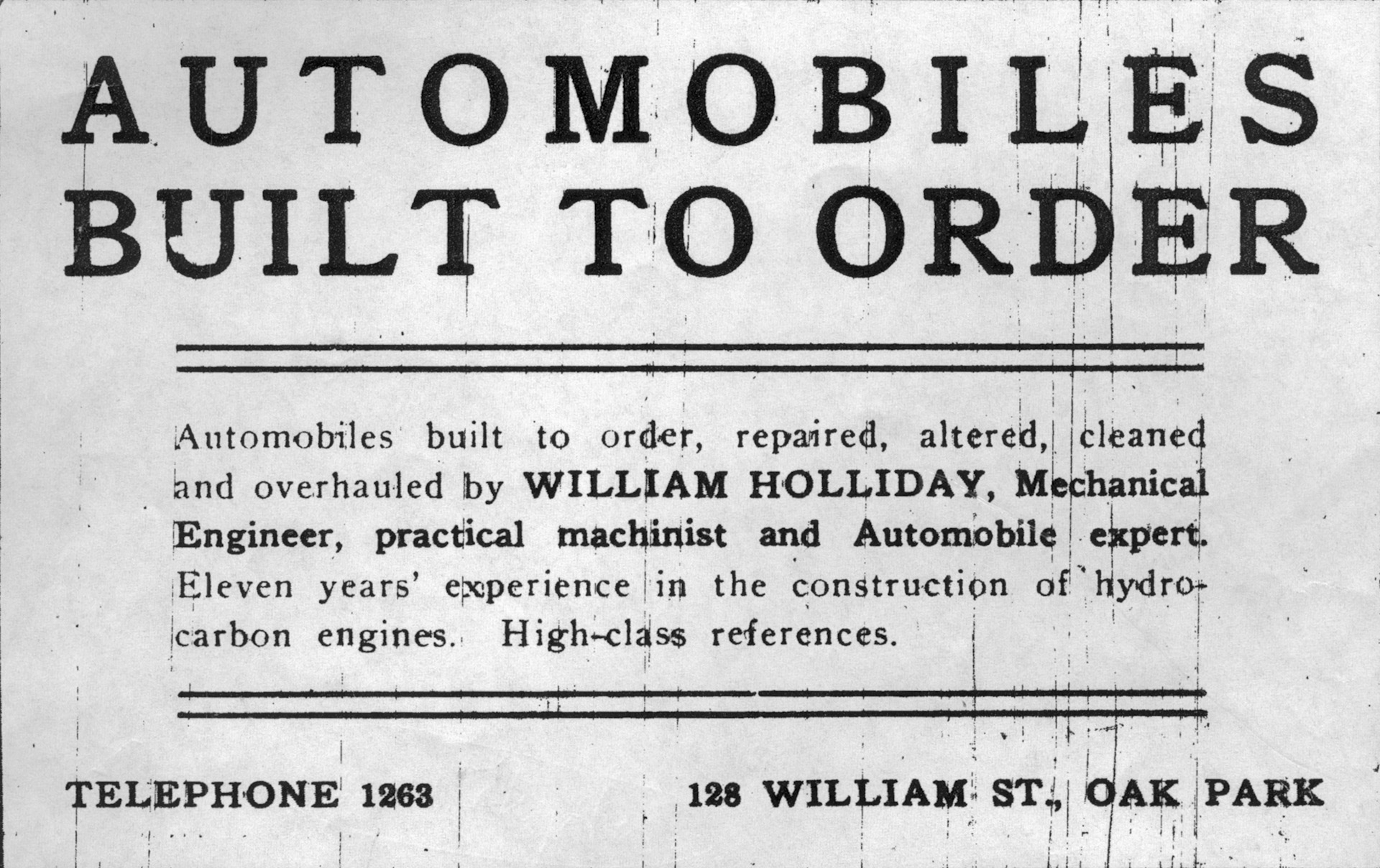

William Holliday was an entrepreneur who designed and made automobiles in his machine shop across the street from Mt. Carmel Baptist Church, in the heart of Oak Park's Black neighborhood. This 1907 ad in the local newspaper, the year before Henry Ford launched his Model T, touts experience dating to 1895.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

The 1920s marked an early high point of the Black Oak Park community, with 169 residents among the Village’s nearly 40,000 inhabitants. One-third of the Black population was born in Illinois, with the rest hailing from 22 states and Canada. Black Oak Parkers were mostly employed in service sector jobs, but many were also entrepreneurs and small business owners like Willis and Emma Walker, who operated a house cleaning company with the help of their two sons. Similarly, Frederick Jefferson owned a garage and auto sales shop, and his wife Gertrude owned a catering business.

Faith Jefferson Jones, left, was one of two documented Black graduates of Oak Park River Forest High School in 1923. She is shown here in an undated photo, likely taken in the mid-1930s with her son Dewey and her parents Frederick and Gertrude.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

Still, Black residents were often viewed as second-class citizens, not fully integrated into the community. In 1914, the editor of Oak Park’s weekly newspaper advocated for Black Americans to be sent to Mexico, asserting, “There is nobody in this country among the white race, except a few theorists and idealists and humanitarians, who wants the Negro here as a friend and brother. The only white men who want him to stay are those who want him to stay as a beast of burden.”

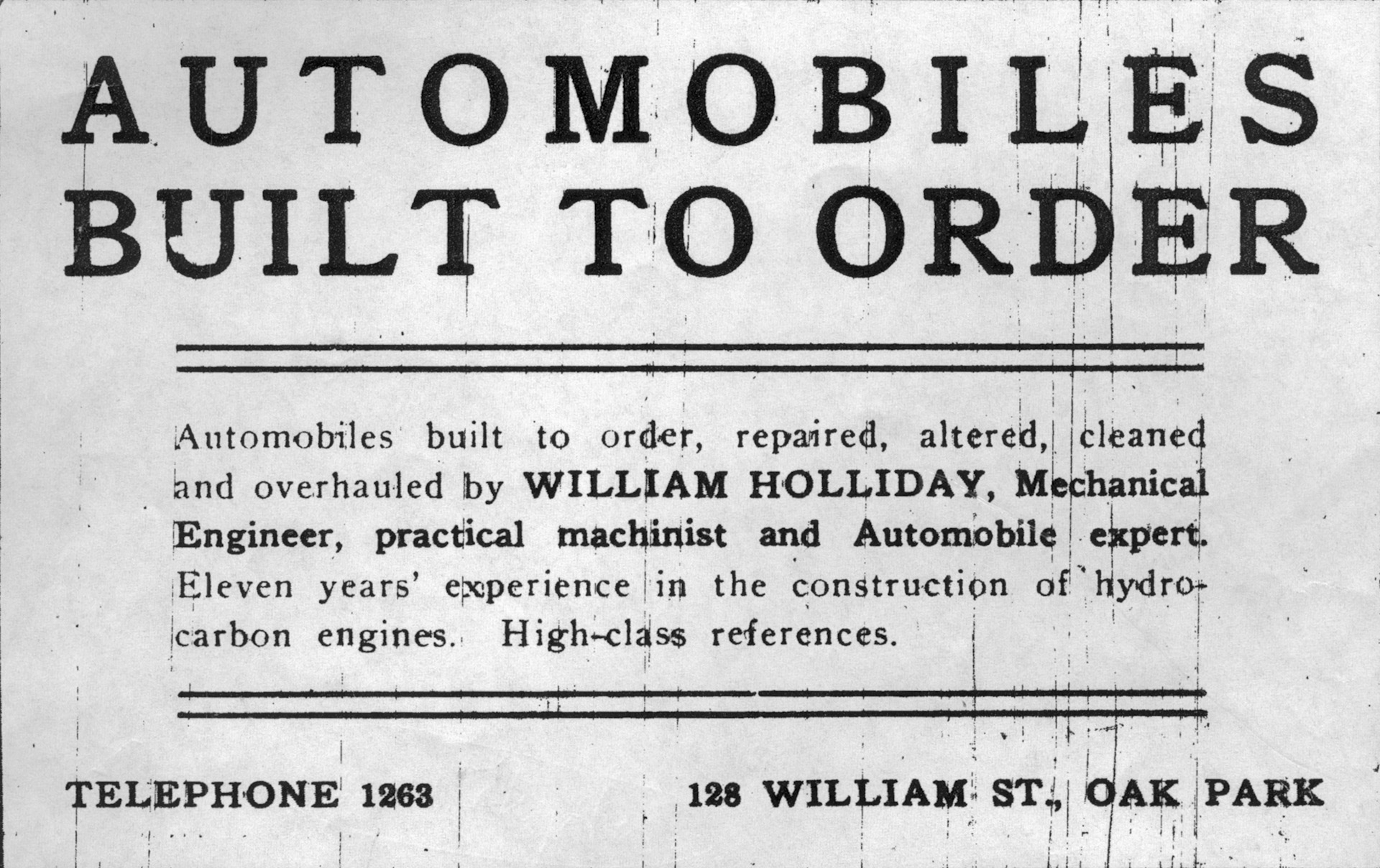

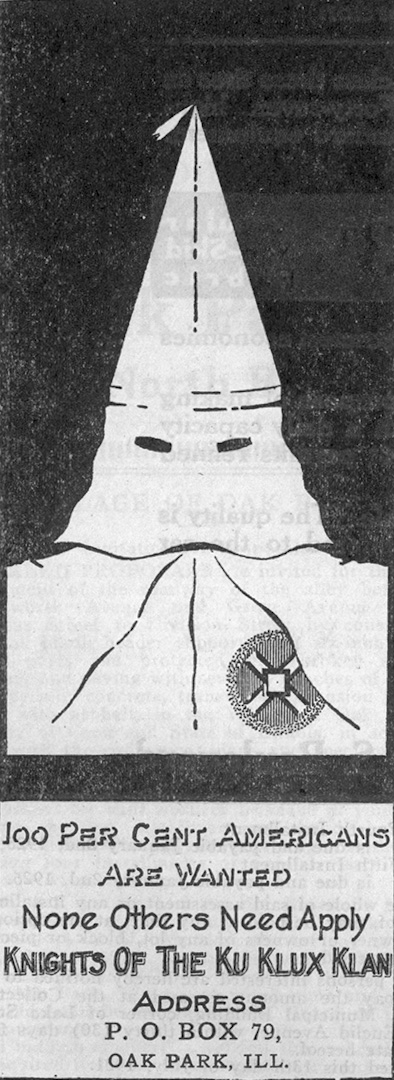

This 1921 advertisement, printed twice in the local weekly newspaper in summer 1921, sought members for the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan of the 1920s in the northern states had roots in the mainstream Protestant churches and was also strongly tied to the temperance movement. Although blatantly and strongly anti-Black, this new KKK focused much of its efforts in opposing the newly arrived Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

The same paper later printed a full-page response from The West End Men and Women’s Club of Oak Park, representing Black Americans who lived and worked in the community. The response stated, “All we ask is equal rights and equal opportunity and the solution will take care of itself…The [editor] says the black man cannot work at a white man’s trade or live in a white man’s street. To this statement we simply ask the question. Why?”

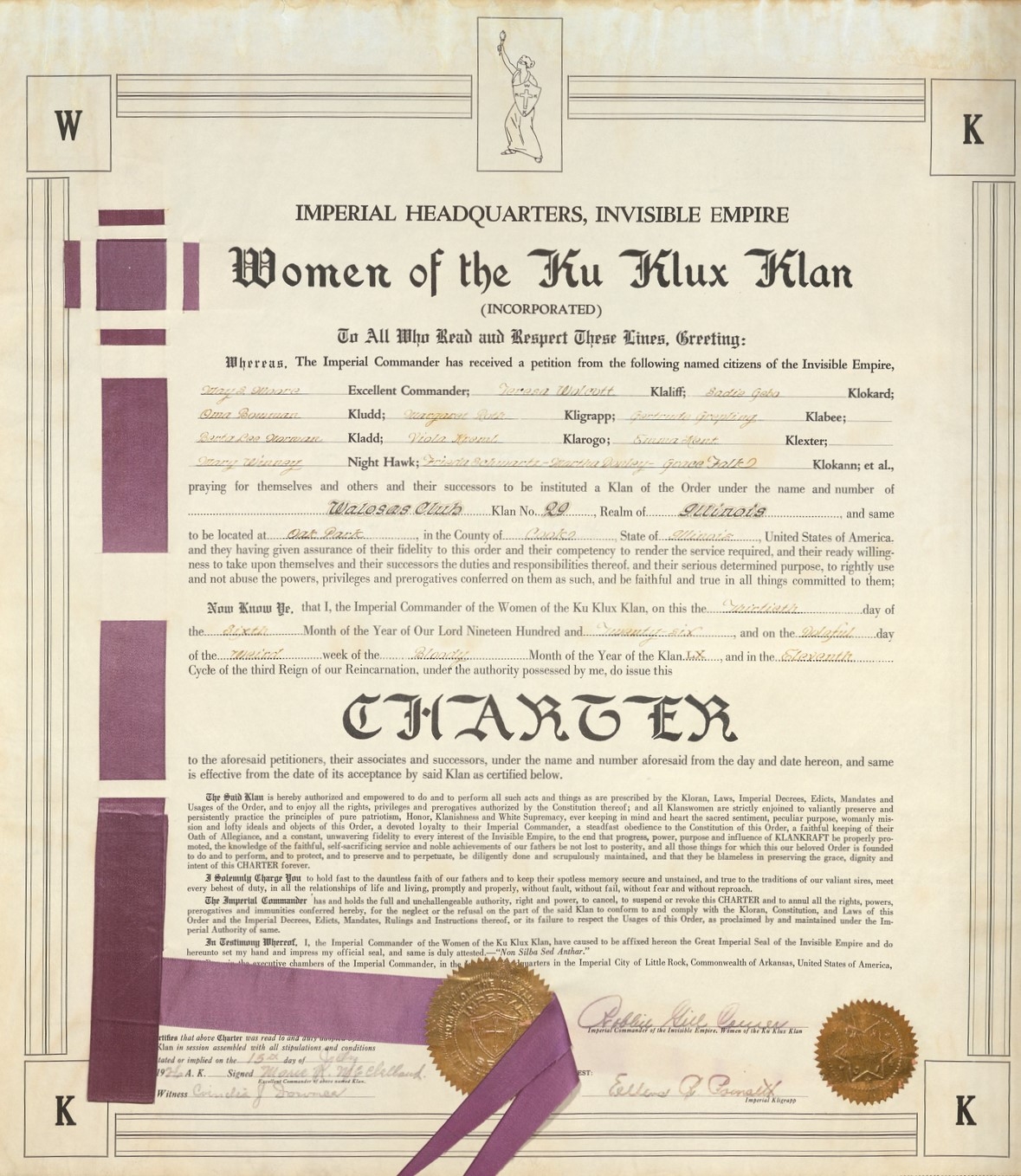

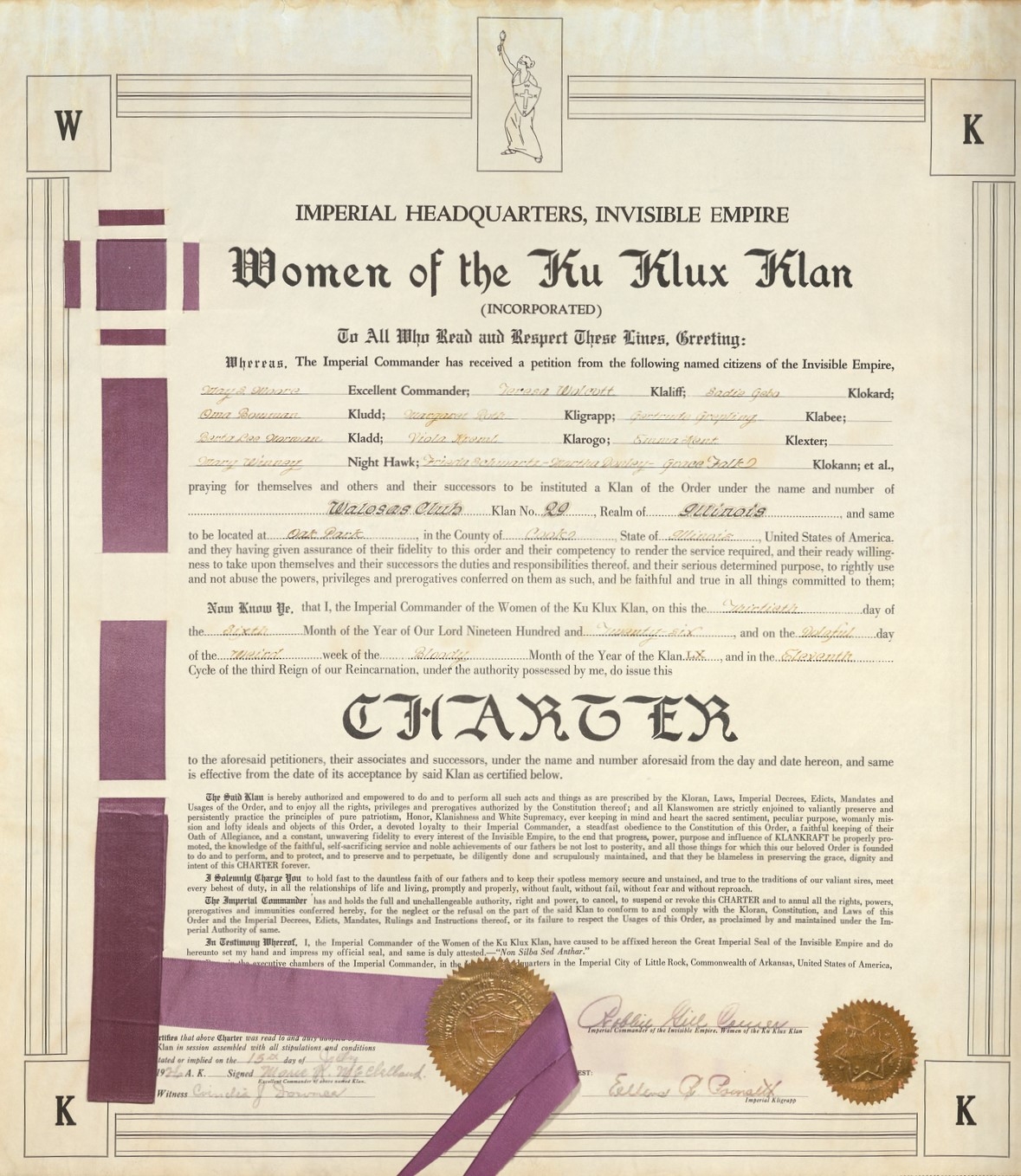

A new chapter of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan was chartered in 1926 in Oak Park, though area Klanswomen had been meeting since 1924. This autonomous organization grew out of the rebirth of the KKK but was self-governing and not under the auspices of the men's KKK. Note the innocuous name the Walosas Club on the 1926 charter, further cloaking the secret society in the shadows.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

This was not a hypothetical question. That same month, the home of Frederick and Gertrude Jefferson was firebombed. Though the Jeffersons did not know it at the time of purchase, a builder sold homes to them and another Black family in retaliation for an argument with White neighbors. The Jeffersons had lived there several years before this violent act of racial hatred occurred. While the local newspaper buried the story on page 12 with minimal details, the leading national Black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, provided front-page coverage under the title, “Oak Park Incendiaries Attempt to Burn Jefferson Family Alive.” The Defender identified the event as “another attack of colorphobia.” No formal charges were ever filed.

But a lot of this 1920s Klan is an urban based as well. It's not something that's happening in small rural communities. It is very much present in urban and suburban America.

Historian

ViewHide Transcript

You have William Joseph Simmons reviving it in 1915. He never really gains that much momentum, not very effective at thinking of it as a broader sense, borrows the name borrows the alias invisible empire that came with the original Reconstruction-era Klan. But there really is nothing invisible about this 1920s Klan. They are very clear and kind of flaunting who is their membership.

They're not hiding in the fringes. They're not, you know, operating mainly at night, terrorizing freedmen at night. They are very much front and center. They are publicly advertising in newspapers for 100% Americans. They are holding these large public gatherings, bazaars, inviting the whole family kind of membership, recruitment drives, rallies. In 1925, they had this major march with 30,000 members through the streets of Washington, D.C.

So yes, it's very much a Klan operating in front and center in the daylight, and it's attracting mainstream Protestants. So these aren't kind of fringe elements of society. They're attracting your everyday White Protestant Americans to their ranks. You have different levels of Klan activity in different parts of the country. We think about this 1920s Klan. As we said, it's very much expanded beyond the former Confederate states. Almost 45 percent of the membership of the 1920s Klan comes from the states of Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois. But a lot of this 1920s Klan is urban-based as well. It's not something that's happening in small rural communities. It is very much present in urban and suburban America.

A key detail The Defender included was that the people who were questioned in relation to the Jefferson firebombing were all White women who had reportedly made verbal threats against the Jeffersons. This was not mentioned in the Oak Park newspaper. The changing demographics of Oak Park, including an influx of Roman Catholics and newer immigrants, proved attractive to recruiters of the revived Ku Klux Klan (KKK). In the summer of 1921, the KKK arrived in Chicago with an anti-immigrant message, taking out two recruitment advertisements in the local paper for an Oak Park chapter. A few years later, an Oak Park chapter of Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) boasted over 300 members. The primary concern of the WKKK within Oak Park was not the small Black or Jewish communities but rather the major influx of Catholic immigrants coming from Chicago.

Louise Stewart Shannon and her husband J.W. Shannon in front of their home at 838 Belleforte in 1937. A few years after the Mt. Carmel Baptist Church was demolished in 1931, the local Black population began to dwindle from its high in 1920. Daughter Virgie Shannon Peerman recalled that her parents' friends urged them to move from Oak Park and her mother replied: "This house up here on Belleforte is mine. It's long been paid for. You all go ahead and go."

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

Incidents like the Jefferson family home firebombing hindered the full participation of Black residents in Oak Park’s community life. As the Depression loomed, opportunities for Black residents dwindled. In the late 1920s, White Oak Park businessmen sought to redevelop the central business district to attract major Chicago department stores and large retailers. The campaign included plans to expand into the Black neighborhood. A series of suspicious fires were set in and around the Mt. Carmel business district. By the early 1930s, the church and many of the remaining Black-owned homes and businesses had been bought and demolished. The historic Black neighborhood anchored by Mt. Carmel disappeared as the central business district became the largest retail hub in Chicago’s west suburbs.

In 1937, a Black football player at the local high school was disinvited from an exhibition game in Florida. In response, world-renowned chemist Dr. Percy Julian pointed out Oak Park’s hypocrisy in paying lip service to racial issues. He cited the local YMCA’s rejection of his request to rent a room just a few years prior. In 1939, some White residents presented a plan to the Oak Park Real Estate Board to use restrictive covenantsRestrictive covenants: Agreements in contracts that prohibit buyers from taking certain actions after they purchase a property. Although covenants can pertain to any number of restrictions on property ownership or use, during the early-twentieth century it was commonplace to have restricted covenants preventing a buyer of a specific racial, ethnic, or religious group. to ban the sale of property to Black residents in the fashionable northwest corner of Oak Park, which was never acted upon. But the message was clear. Blacks were not welcome. Oak Park’s Black population steadily declined over the next few decades, reaching an all-time low of 57 in 1960.

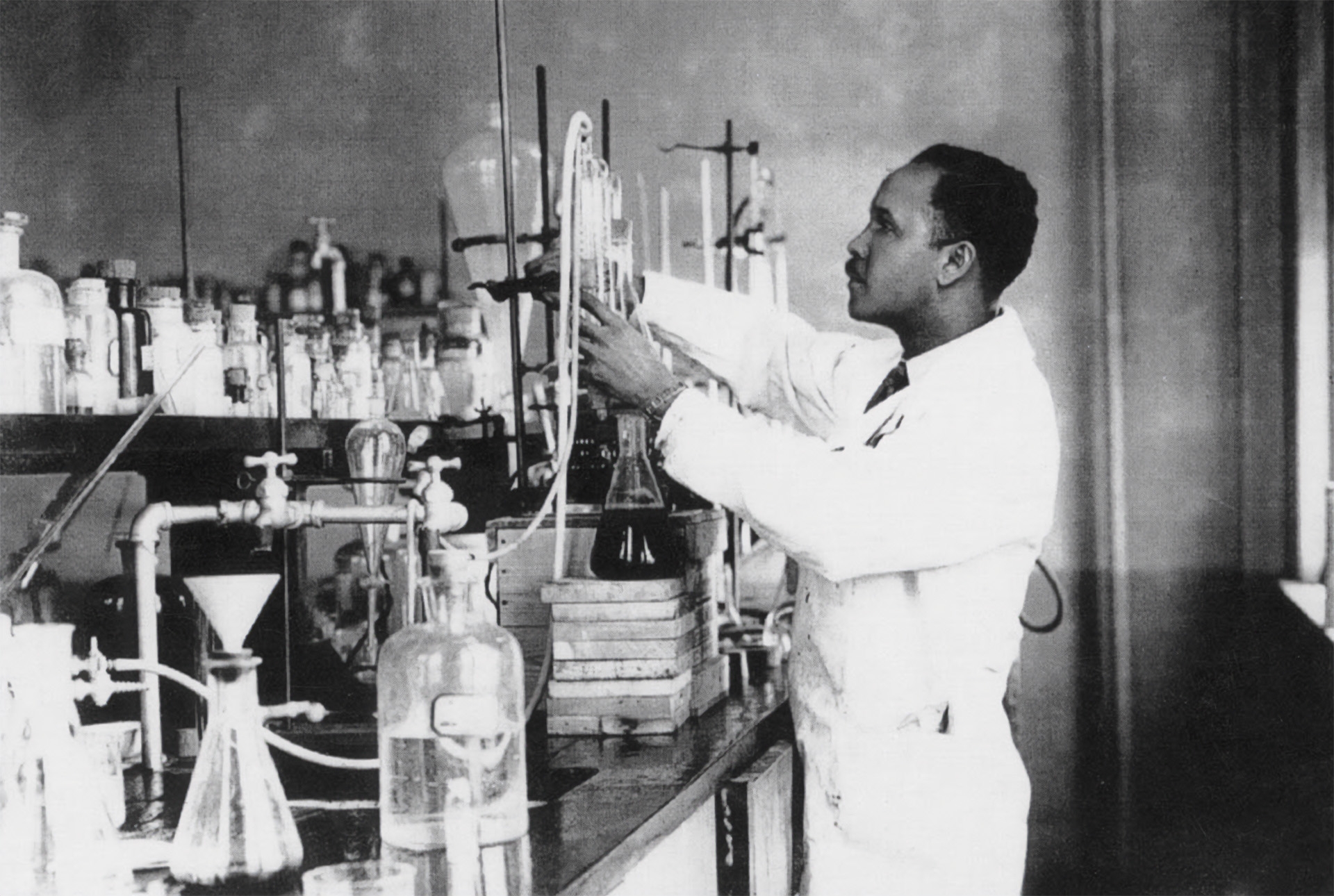

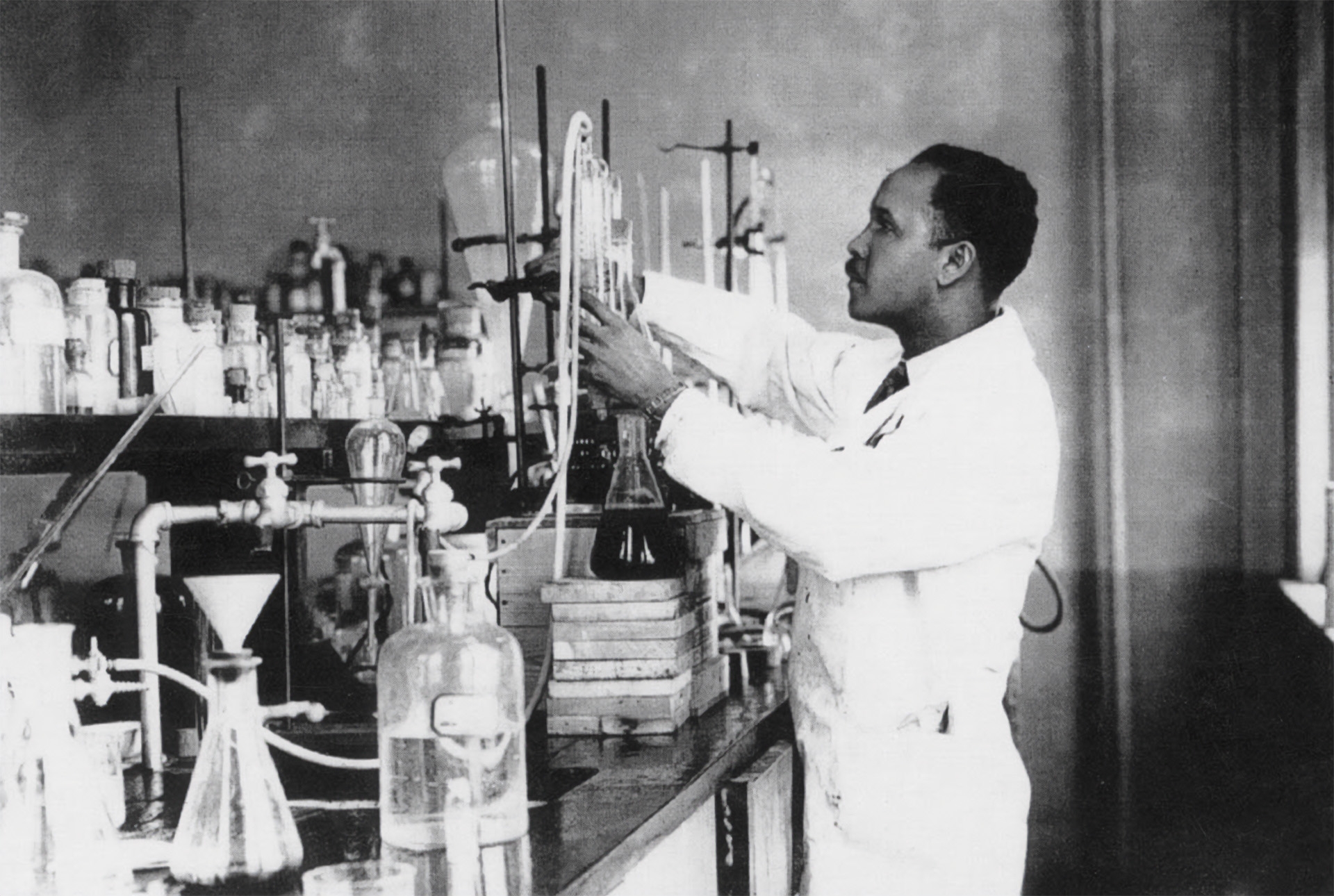

Dr. Percy Julian was a renowned chemist and entrepreneur who discovered ways to synthesize medical compounds from plant materials, making steroids more affordable and therefore available to more people. His medicinal formulations are used to treat glaucoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and helped women to carry pregnancies to full term.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

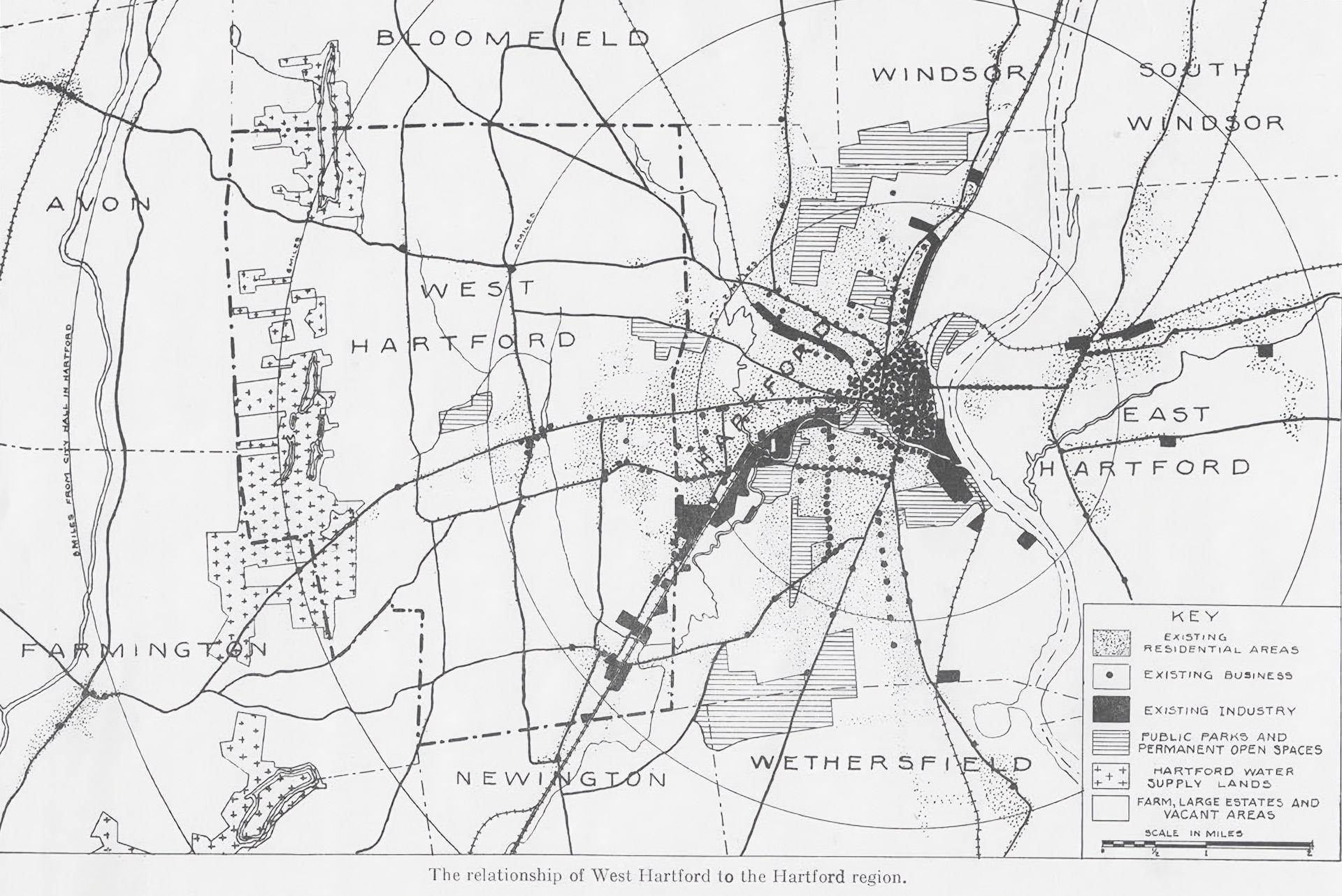

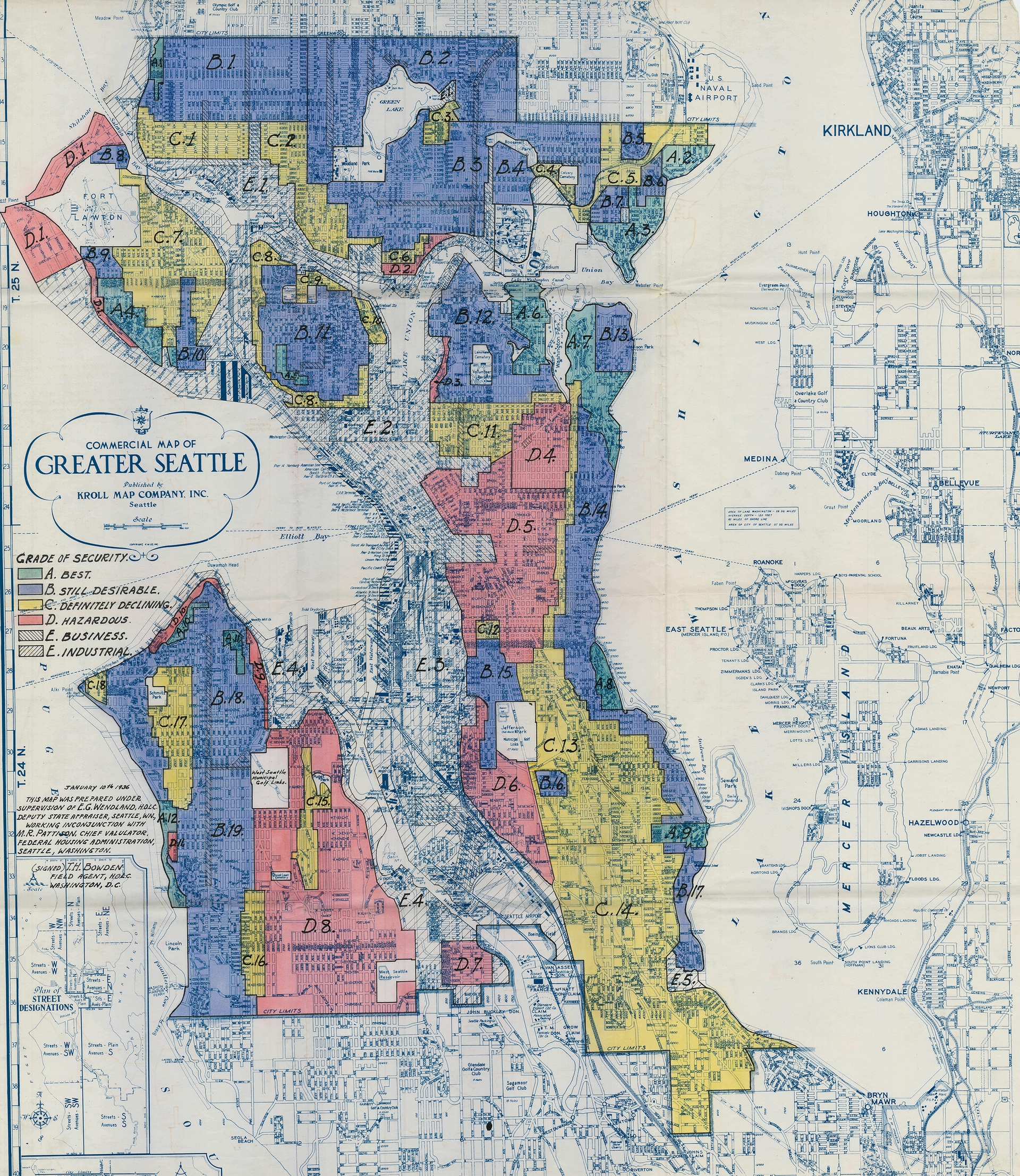

In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC)Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC): A government-sponsored corporation founded with the Home Owners’ Loan Act (1933) as part of the New Deal. They issued bonds to fund the refinancing of mortgages from people struggling to afford their homes during the Great Depression. From 1935-1940, the HOLC commissioned a series of security maps for cities and towns that ranked and color-coded neighborhoods according to risk assessment. The racial and ethnic makeup of neighborhoods was a significant component, leading to redlining of Black neighborhoods.

prepared housing appraisal maps for Oak Park, rating nine sections of the village, based on the type of housing and especially the ethnicity and race of their residents. Three sections of Oak Park were rated “B” and shaded blue for “still desirable,” including one well-to-do section of northeast Oak Park that might have ranked higher but for an “infiltration of Czechs, Polish, and Hebrews.” Six sections were rated “C” and shaded yellow for “definitely declining.” The appraisers’ notes for the “C” ratings were justified by the rapid development of multi-unit housing and conversion of single-family homes to two flats and the “infiltration of Italians,” the “presence of Hebrews,” and “presence of Catholics.”

These comments reveal that some European immigrants and Jews were considered “undesirable,” deeming the area a higher risk for mortgage lenders. The HOLC appraisers were especially concerned about Blacks: “One negro family resides in the area, but there is no possibility whatever of any further infiltration,” reported the HOLC. This comment referred to the Shannon family in northwest Oak Park. In an oral history interview, Virgie Shannon Peerman recalled that her parents owned their home outright in the 1930s, while many of their fellow Black residents in Oak Park were renters and unable to remain in the community when properties were sold, and the community became less welcoming to Black residents.

In 1950, Drs. Percy and Anna Julian bought and extensively renovated a mansion in Oak Park’s estate section.

Drs. Percy and Anna Julian purchased this home in Oak Park's estate section in 1950 and began to renovate it but the house was firebombed before they had the chance to move in. The next year someone hurled a stick of dynamite at the house. The incidents caused many in Oak Park to rally to the Julian's aid and to examine community attitudes and policies on race and open housing.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

In 1950, Drs. Percy and Anna Julian bought and extensively renovated a mansion in Oak Park’s estate section. That same year, Chicago Sun-Times named him “Chicagoan of the Year.” This fame did not protect his family from two separate firebombings of their home nor did the protestations of some White neighbors and friends. The Julian family was physically unharmed and quickly repaired the damage to their home. But they were traumatized by the attacks.

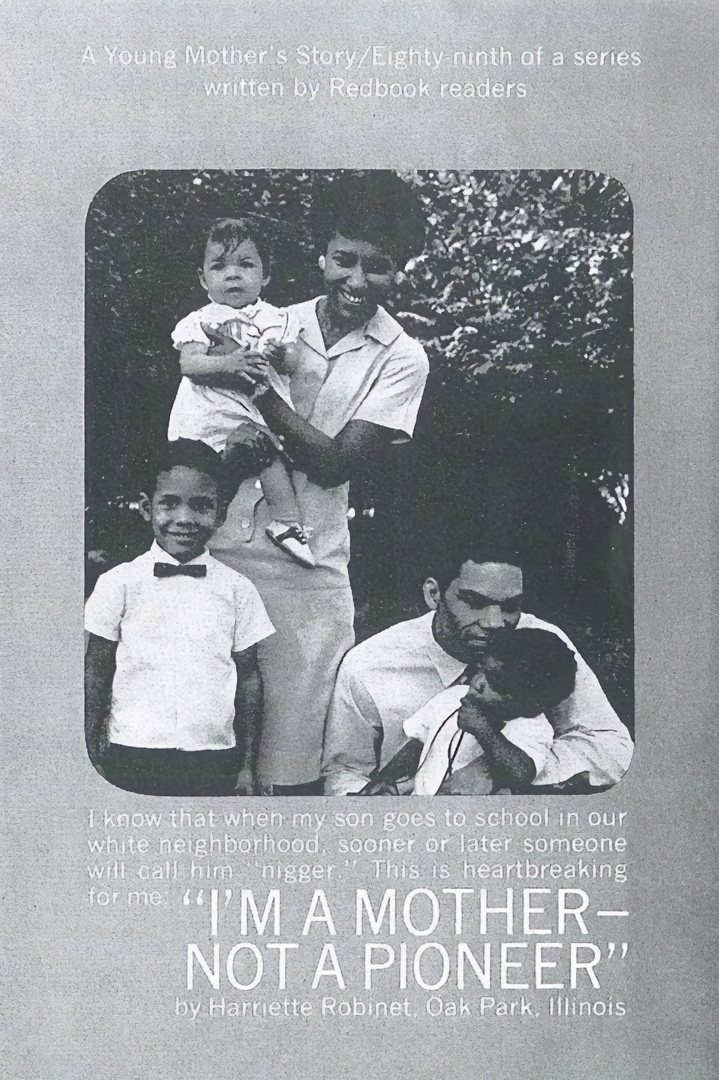

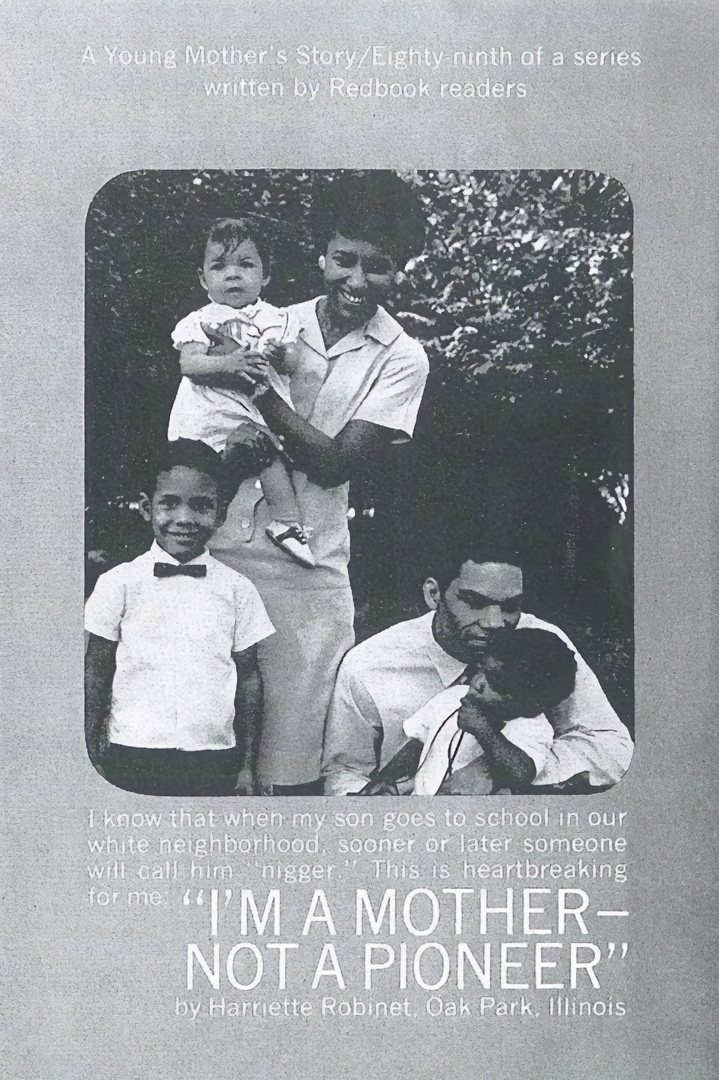

Harriette and Mac Robinet were initially unsuccessful in their efforts to buy a home in Oak Park, hampered by the local real estate industry that refused to show minorities homes unless the current owner agreed to that ahead of time. Finally in 1965, a straw buyer purchased a home on their behalf, immediately selling it to the Robinets. A writer, Harriette described what it was like for a Black family to move into a White neighborhood in this February 1968 Redbook magazine article.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

In 1963, violinist Carol Anderson triggered a reckoning with Oak Park’s racial inequities. After being invited to practice with the local symphony, her presence drew complaints from some symphony members. Though the orchestra’s conductor came to Anderson’s defense, he was overruled by the board president who told newspapers, “We didn’t know if anyone would object to the orchestra being integrated, but we weren’t about to find out on our own. We’re not a band of crusaders.” The public airing of this discriminatory remark embarrassed many; the conductor scheduled Anderson to play at the next concert and resigned from the symphony. A group of local activists began to demand racial equality in the wake of this incident. They formed the grassroots Citizens Committee for Human Rights and successfully pushed for the creation of the municipal Human Relations Commission. Both organizations fought local realtors to end discriminatory practices and worked to reinvent Oak Park as a diverse and inclusive community.

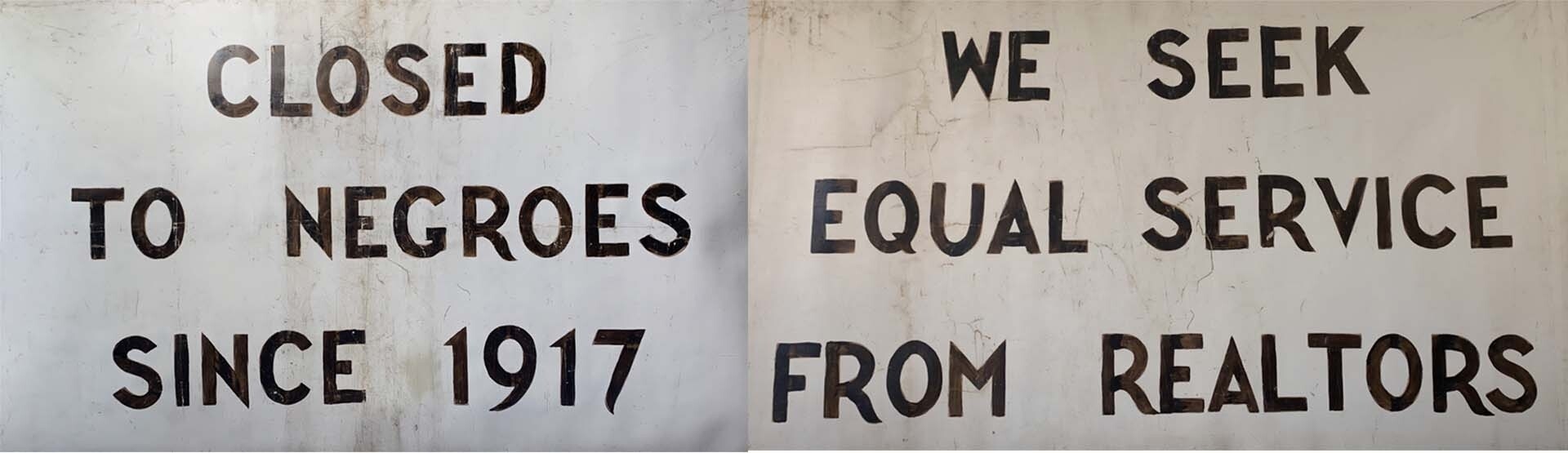

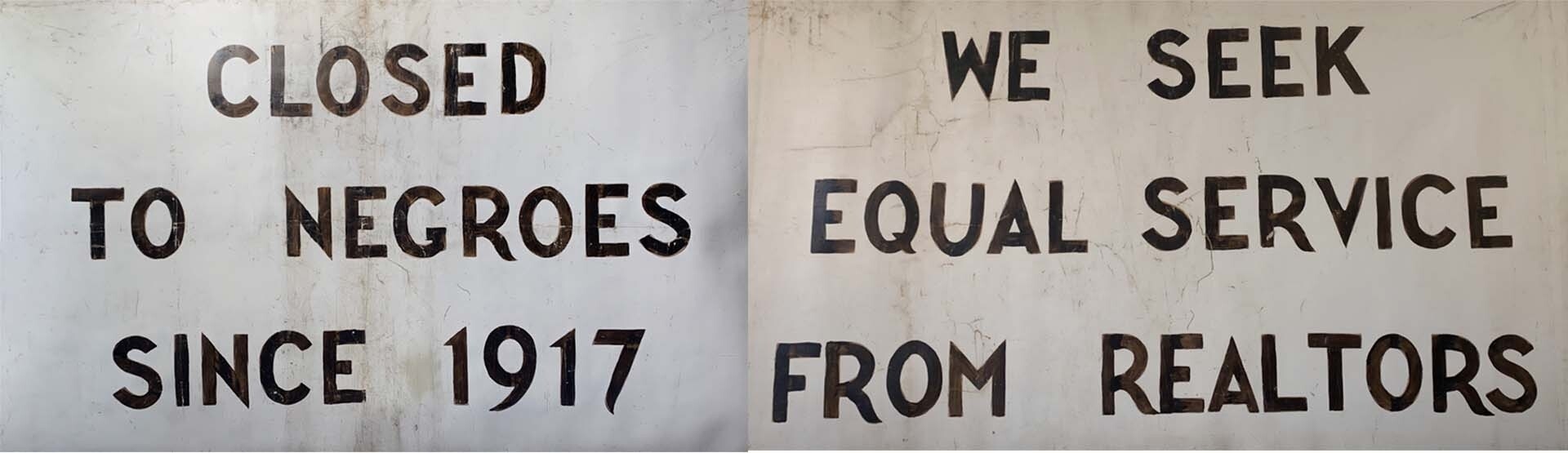

During the summer of 1966, weekly marches demonstrating for a fair housing ordinance in Oak Park targeted the real estate industry which did not support legislation that required equal access for all races. These two banners were carried in those marches.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

Since the 1960s, Oak Park gradually evolved from an elite, majority White suburb into a place known around Chicago and across the United States as a progressive, racially integrated “New Oak Park.” The journey was complicated by resistance and competing visions for this experiment in inclusive living.

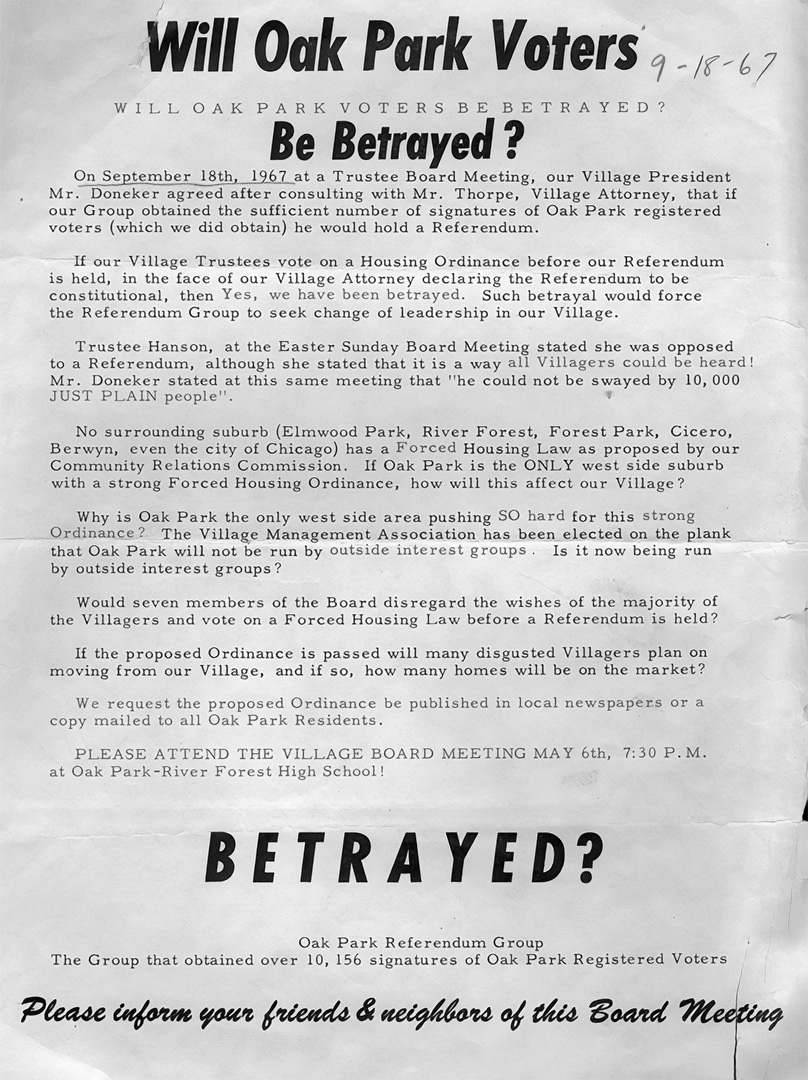

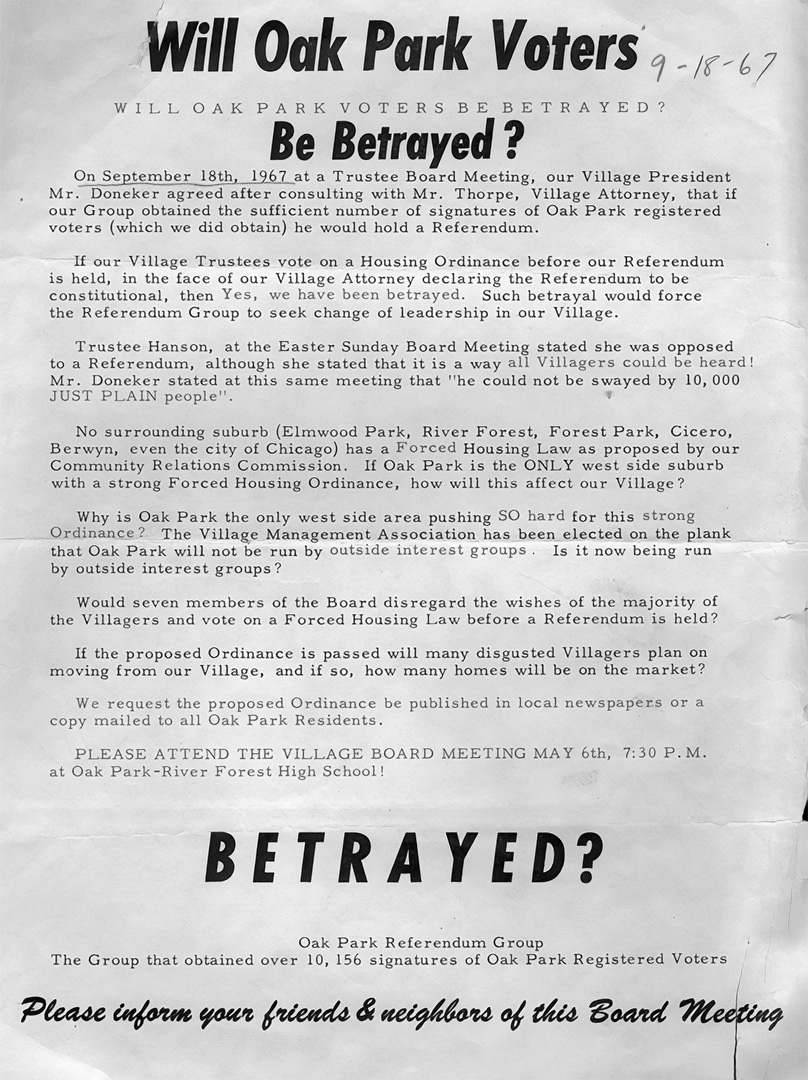

Tens of thousands of Oak Park residents resisted the call for a fair housing ordinance in 1967 and 1968. Some signed petitions against the ordinance, others took out advertisements in the local newspapers, and others made and distributed fliers. A common theme was the idea of forced housing instead of fair housing and the possible infringement of property rights.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

The combination of grassroots organizing, fair housing marches (often called “open housing” in the period), public testimony, and behind-the-scenes maneuvering resulted in the approval of a local fair housing ordinance in 1968. Oak Park banned “For Sale” signs to discourage White flightWhite Flight: The process by which White Americans, driven by the fear of rapidly shifting neighborhood demographics, moved in large numbers to different areas. In the mid-twentieth century US, this process often involved White Americans abruptly moving from urban areas to new suburban developments leaving more economically vulnerable communities of color left in cities which were experiencing disinvestment., established a home equity insurance program, created the Oak Park Housing Center to fight for racial integration, actively enforced housing law, and addressed racial inequities in the public schools.

And so it's kind of a message, this community is going through racial change. And we did not want to give that kind of message.

Fair Housing Activist

ViewHide Transcript

The village with the recommendation by the commission, from the commission, that there be a ban on for sale signs. Because what tended to happen, and what still happens as a matter of fact today, is in a community that is predominantly White you see no for sale signs. When Blacks start to move in, all of a sudden for sale signs go up and they go up in abundance. And so it's kind of a message, this community is going through racial change. And we did not want to give that kind of message. So we encouraged the commission, to encourage the board of trustees to pass a ban on for sale signs. And they did. As a matter of fact, in 1977, the Supreme Court came down with the decision having to do with a case in Willingboro, New Jersey, that the ban on for sale signs was unconstitutional. And our board of REALTORS® said here as long as it was on our books, the village's ordinance was on the books that they would continue the ban. And it's interesting because in '73, when it was passed, the board of REALTORS® did not like it.

They thought it was awful to have the ban, but what they found was that they were able to sell houses at the same rate, if not a better rate without the signs. And they did not have outside REALTORS® coming into the community and trying to sell houses because you couldn't have a sign. So therefore people didn't know who you were and members of the Oak Park River Forest Board knew what houses you could come in their office and look at their, all the listings, and not just look at a house that had a sign on it. So they found by '77 that it was beneficial to them not to have the signs. And even today we don't have signs.

The new philosophy was one of active, ongoing efforts to retain Whites, recruit underrepresented residents, and demonstrate that racial integration was desirable and could be sustainable. However, many in Oak Park rejected this new direction through active protest. Some real estate agents still refused to show properties to all interested potential renters and buyers. In response, the Housing Center and grassroots activists investigated violations of the Fair Housing Ordinance by using a diverse group of testers, sending potential buyers of different races to meet with brokers to see if they received equal service and access when attempting to view listed properties.

Weekly protest marches through the streets of Oak Park in the summer of 1966 targeted the discriminatory practices of local real estate agents. Since some criticized these marches as being organized by outsiders, many of the protesters emphasized that they were Oak Park homeowners or residents. Others pointed to the solidarity between Black and White marchers and the guarantee of equality found in the nation's founding documents and represented by the Liberty Bell.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest

In the years since the passage of the Fair Housing Ordinance, the pursuit of racial inclusion has become a prominent part of Oak Park’s identity. It has been an imperfect process of managed integration that is still ongoing. Today, a socioeconomically, racially, and religiously diverse range of people call Oak Park home, including a visible LGBTQIA+ community and sizable Black, Jewish, Asian, and Latino populations. However, disparities remain, fueling ongoing community conversations, grassroots advocacy, and government action to ensure that Oak Park lives up to its contemporary reputation as a progressive community rooted in intentional inclusivity.