Local Spotlight

Brea, California

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

Community Profile

- Community: Brea, 1911

- County: Orange

- State: CA

- Type: Suburb

- Metro: Los Angeles

Located in North Orange County, the City of Brea sits on the ancestral homelands of the Kizh/Gabrielino/Tongva people. In July 1769 the Spanish Portola expedition, which camped in Brea Canyon, became the first Europeans to make land entry and explore Alta California. Oil, discovered in Olinda in 1894, led to the development of Randolph, later named Brea. Oil dominated the region’s economy, but agriculture also played an important role. The construction of the Orange (57) Freeway and the Brea Mall supported increased residential growth in the 1970s. Today, Brea is 40% White, 30% Hispanic/Latino, 24% Asian and 2% Black.

Community Statistics

- Owner-Occupied Housing Units: 62.3%

- Median Value of Owner-Occupied Home: $660,400

- Median Gross Rent: $1,851

- Median Income: $94,492

- Poverty Level: 6.4%

- High School (ages 25+): 92.6%

- Bachelors (ages 25+): 45.3%

Data Sources

Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice

Applied Geographic Solutions & GIS Planning

Life Behind the Orange Curtain

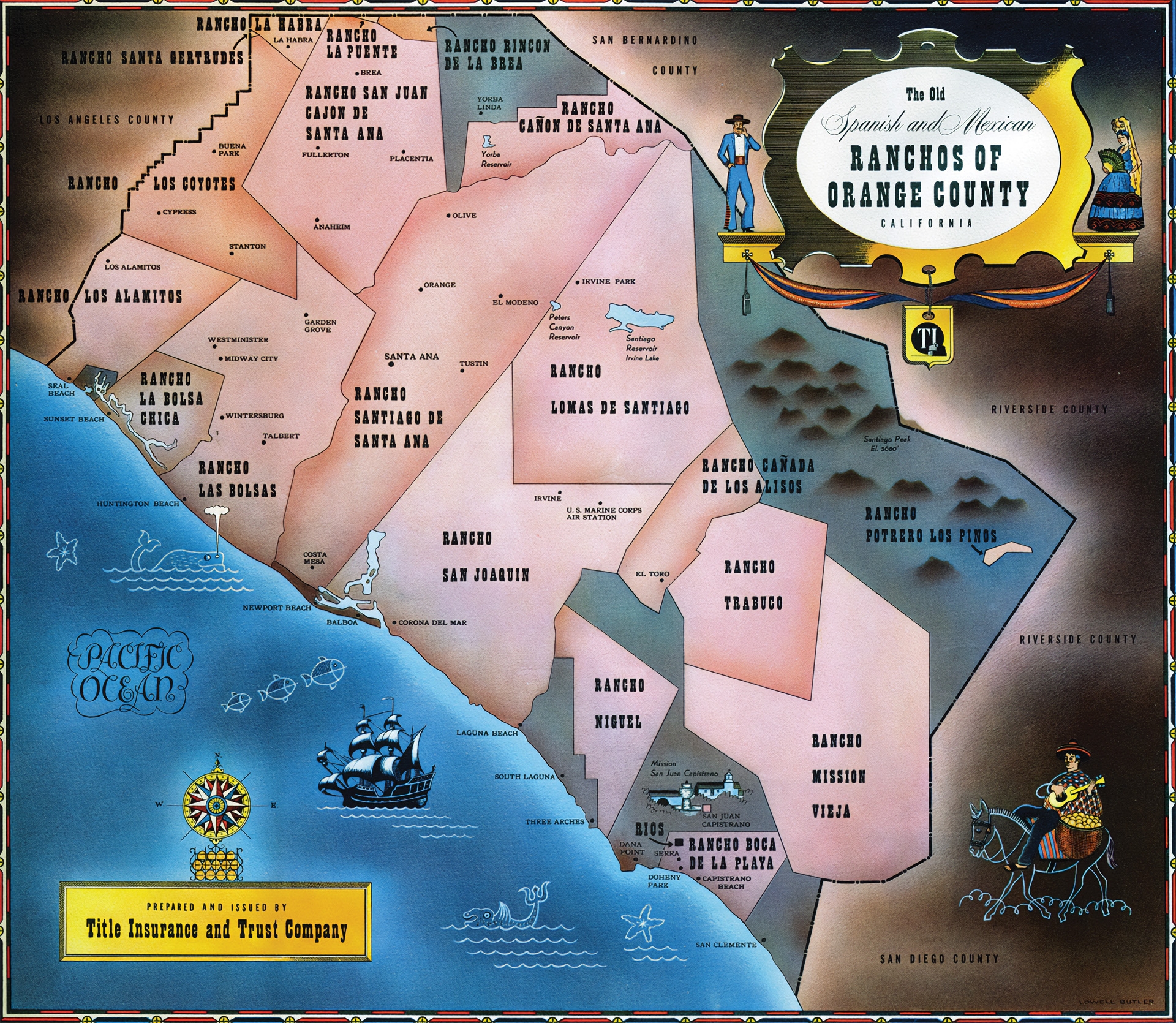

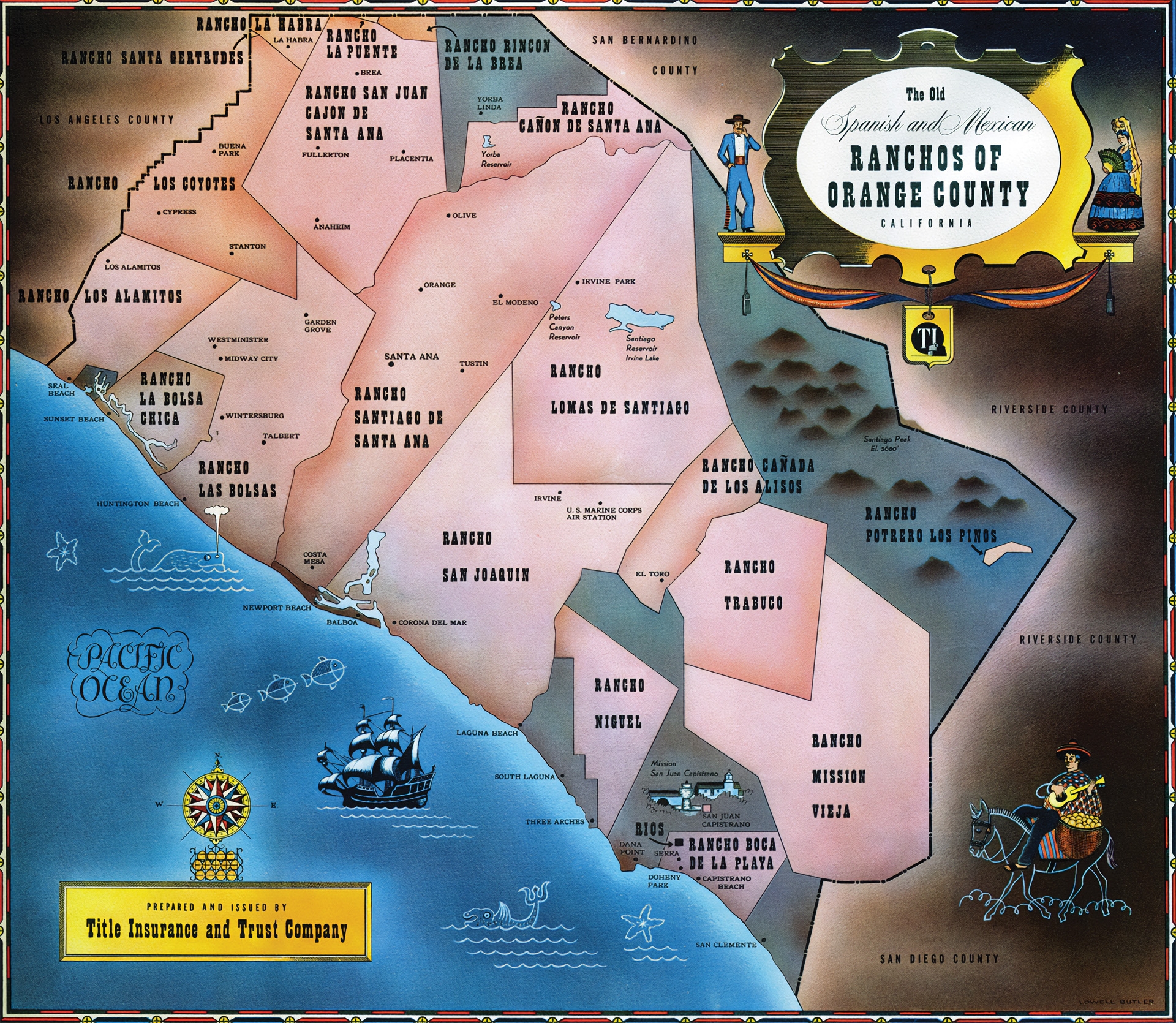

Brea is Spanish for tar and connects the city to its history of Spanish colonization, Mexican settlement, and to its early days as an oil boomtown. After centuries of property ownership, divided under the ranchero system,Ranchero System: After colonizing the area now known as southern California, the Spanish and Mexican governments established a land-use structure called ranchos (large tracts of land dedicated for grazing livestock, typically cattle or sheep). Over time, government properties were awarded by land grants to individuals which eventually became the basis for the survey system in California with ranchero names carrying over to maps and titles. oil prospectors came seeking “black gold” in the area’s tarry hills. In 1894, the Union Oil company bought 1,200 acres of land near the settlement of Olinda. Four years later, they struck a massive deposit, setting off an oil boom. In the next 25 years, the Brea-Olinda oil field produced 20% of the world’s oil and fueled the growth of a new kind of community.

This illustration shows how large each Rancho was. In 1851 and contrary to the Treaty of Hildago, land owners were required to prove title; a monumental task and the beginning of the demise of the Rancho period.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

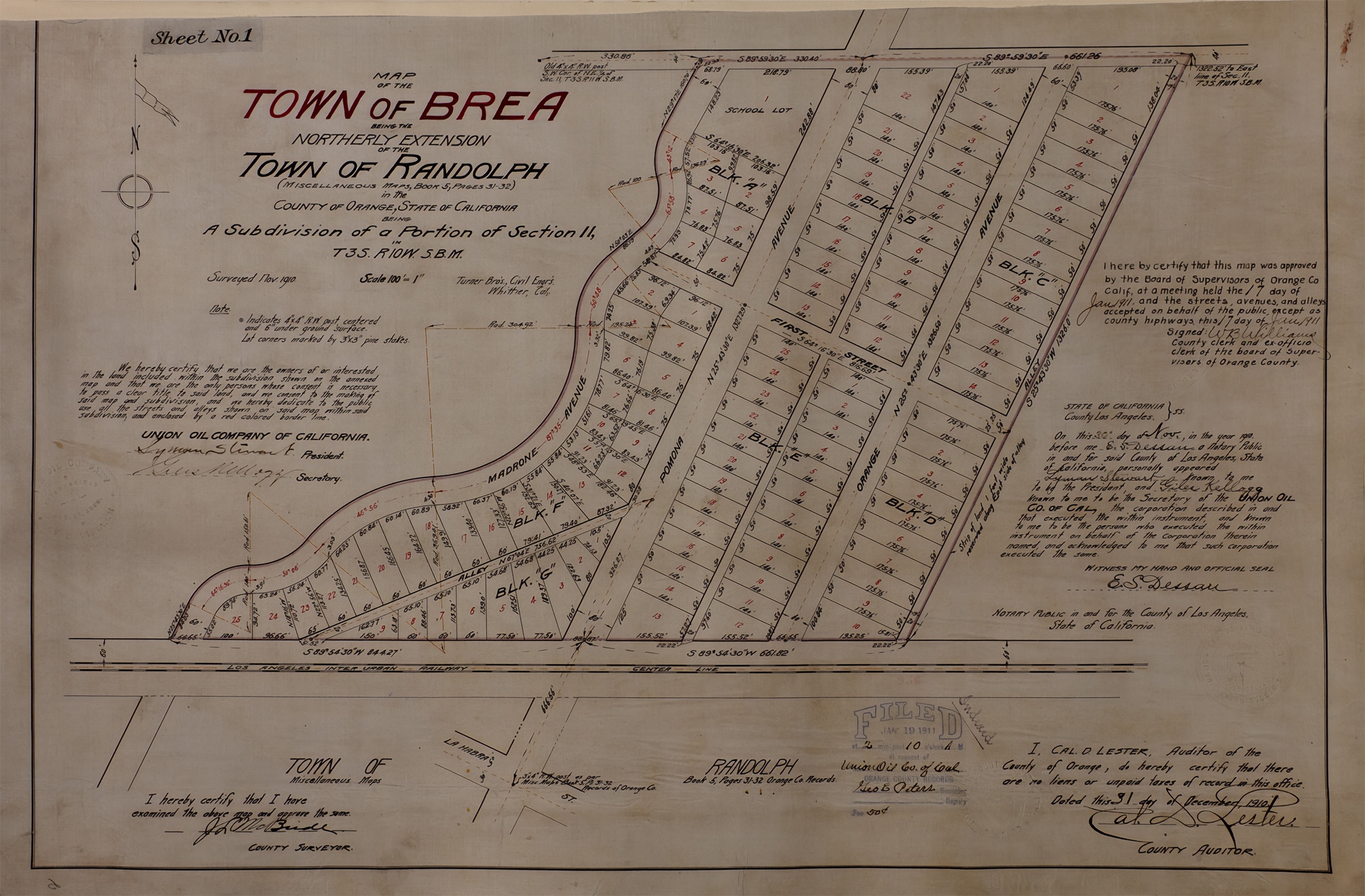

Established in 1911, the town began at the mouth of Brea canyon where a handful of businesses and industries sprang up to serve the growing number of families living on the oil leases. Oil-field culture relied on small, temporary houses that were easily taken down and rebuilt at the next well. But the volume of oil coming out of the hills required long-term workers, and town leaders saw an opportunity for growth.

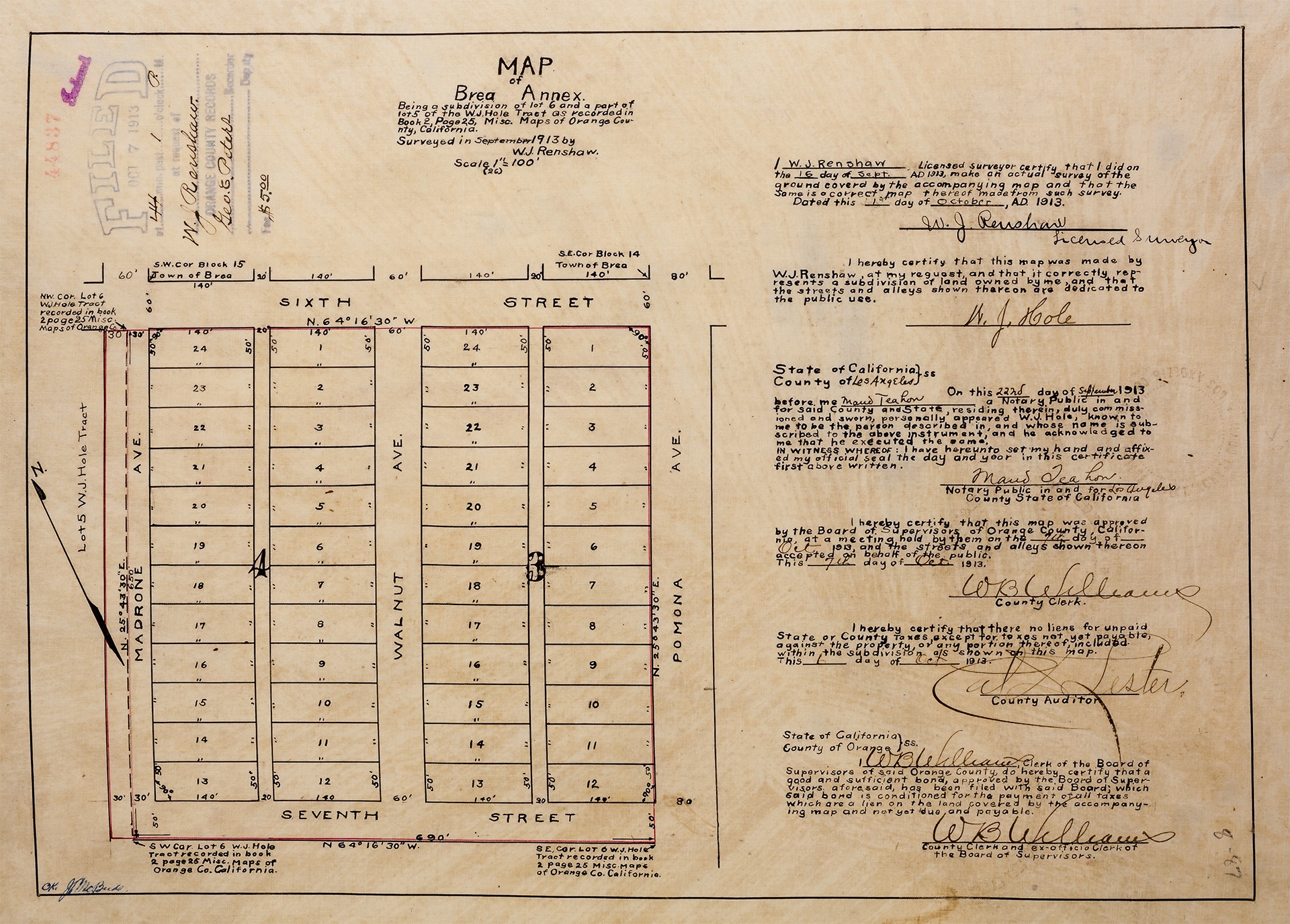

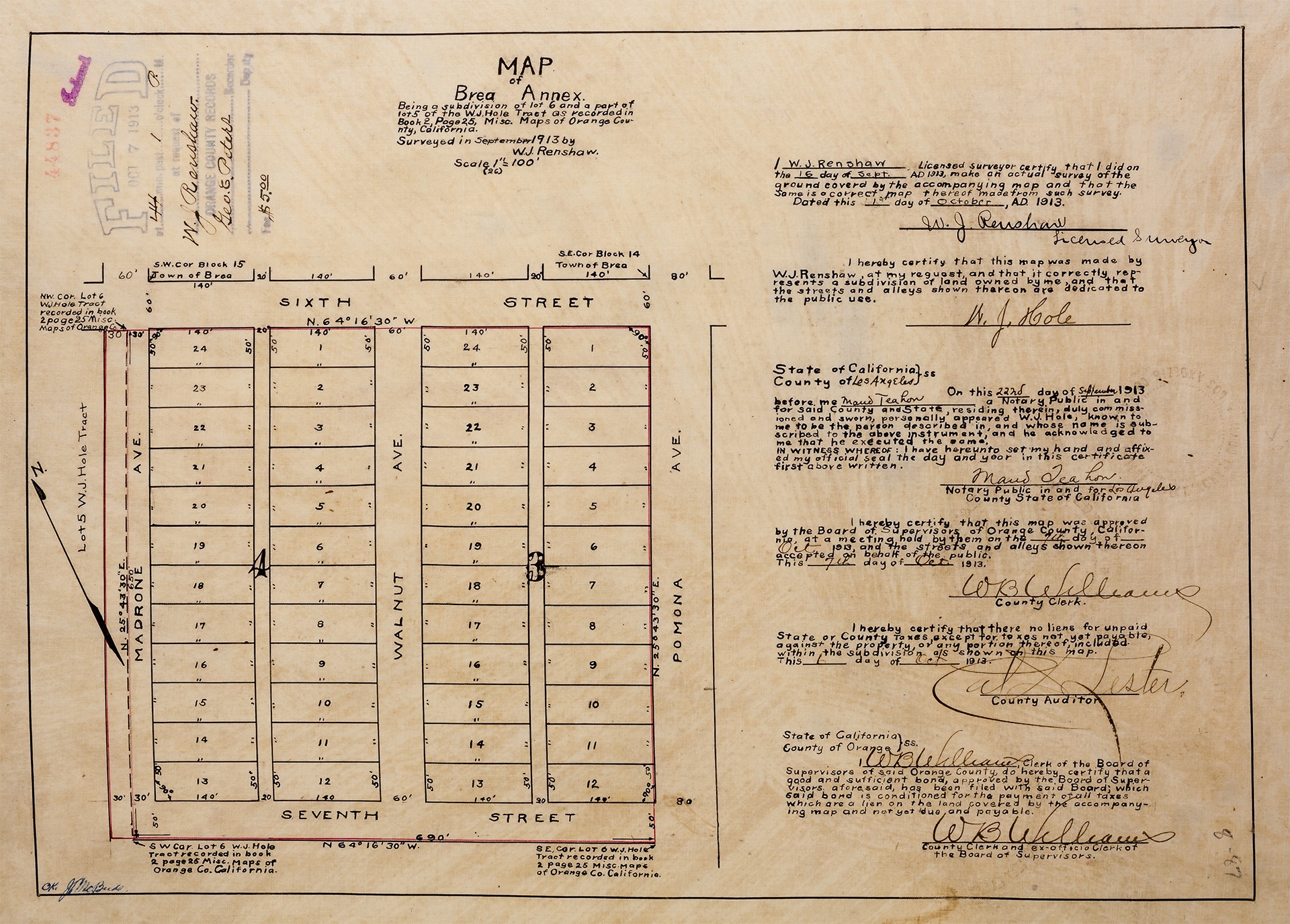

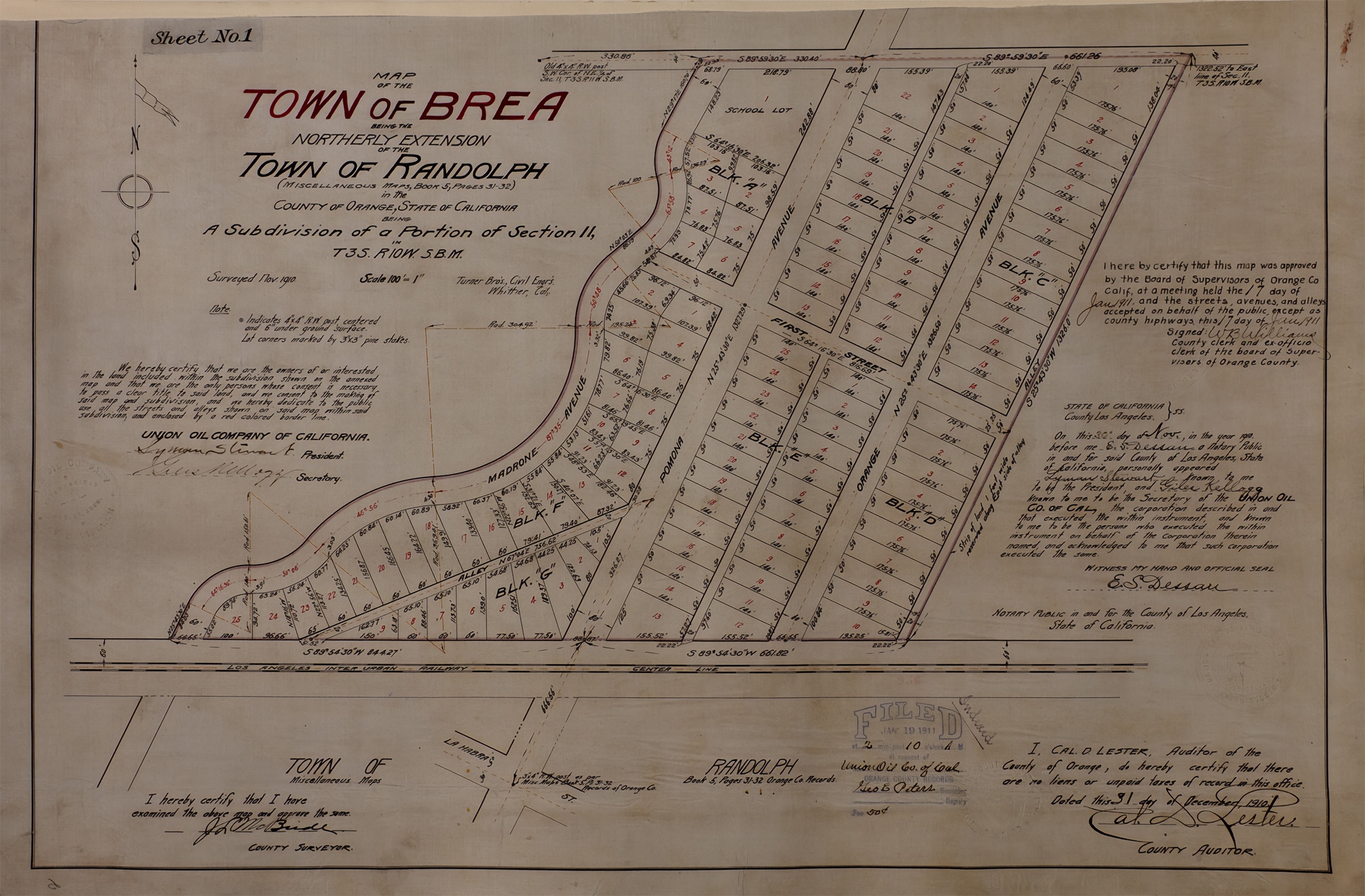

A 1913 map of the newly-established annexations to Brea, CA.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

During the 1920s, Union Oil built 61 homes for their supervisors in the southwestern section of town. As this pattern of investment was repeated, Brea’s population divided into two kinds of housing. Higher income, long-term employees owned their own homes. Transient oil-rig workers were renters.

During the 1920s, Union Oil built 61 homes for their supervisors in the southwestern section of town.

Oil-field culture is generally transient in nature. There is a finite amount of oil so locating and removing it creates an intense drive to drill, barrel, sell, and push on. While oil workers came to the rigs with a hope of striking it rich, the reality was often very different. Homes were simple wood structures that were easily dismantled and rebuilt at the next well.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

In 1917, Brea was incorporated into Orange County. Almost immediately, city trustees passed ordinances to regulate alcohol consumption, loitering, and lewd and vulgar behavior. Nationally, vagrancy laws like these were commonly used to harass people deemed “undesirable” or “nuisances.” Often, the targets of these laws were people of color.

In 1919, employees and their families wore their best to attend the first annual Standard Oil picnic.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

During the 1920s, various restrictive covenants targeting specific racial and ethnic groups prohibited people of African, Chinese, and Japanese descent from residing in Brea. While restrictive covenants were not included in every deed, this established practice enabled buyers and sellers to designate areas as “Whites only.”

On January 19, 1911, W.J. Hole filed a new map with the County Recorder, changing the name to Brea and expanding the town by several blocks. In 1917, Brea was incorporated into Orange County.

Courtesy of Orange County Public Records

Sundown townSundown Towns: All-white communities or counties that purposefully maintained their status through harassment, discriminatory laws and ordinances, and violence or threat of violence. The name comes from posted and verbal warnings that Black people and other people of color would receive upon entry. Sometimes this status was codified in law and signaled with signs, sirens, or other warnings. Often, laborers such as household, farm or factory help could work in a community during daylight hours and had to leave town by sundown. Frequently, it was maintained by practice and custom of local people and law enforcement. Sundown towns appeared in many areas of the nation between 1890 and the 1970s with some still maintaining their all-White status. practices helped to maintain Brea’s mostly White population. In 1982, Brea resident Alice Thompson recalled “there were no Negroes in Brea; they were not allowed.” Thompson linked those practices to the strong presence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in Brea during the 1920s, noting that all the men she knew, including her father and future husband, were members of the KKK. In the 1920s, the KKK had great power and influence in Orange County. In 1924, an estimated 20,000 people came to see the initiation of 1,000 new Klansmen in nearby Anaheim.

Former Police Chief Don Forkus also recounted sundown practices in a 1982 interview. While no official ordinance banning Blacks from the town existed, Forkus recalled the clear understanding that Black people were prevented from staying overnight:

I grew up as a child in this town with the impression that that's the way it was. I had an uncle that owned a barbershop downtown in the 100 block of South Brea Boulevard. Outside his barbershop was a shoeshine stand, and the man that was the shoeshine man was Black. I think he lived in Pomona. I went in there to get my hair cut, and on occasion there'd be some comment made about the fact that he had to shut down and be out of town before the sun went down, because it was either an ordinance or an awfully strong expectation--one of the two, I don't know.

—Don Forkus, ResidentAn official ordinance was unnecessary as residents clearly understood that Black people were not welcome overnight.

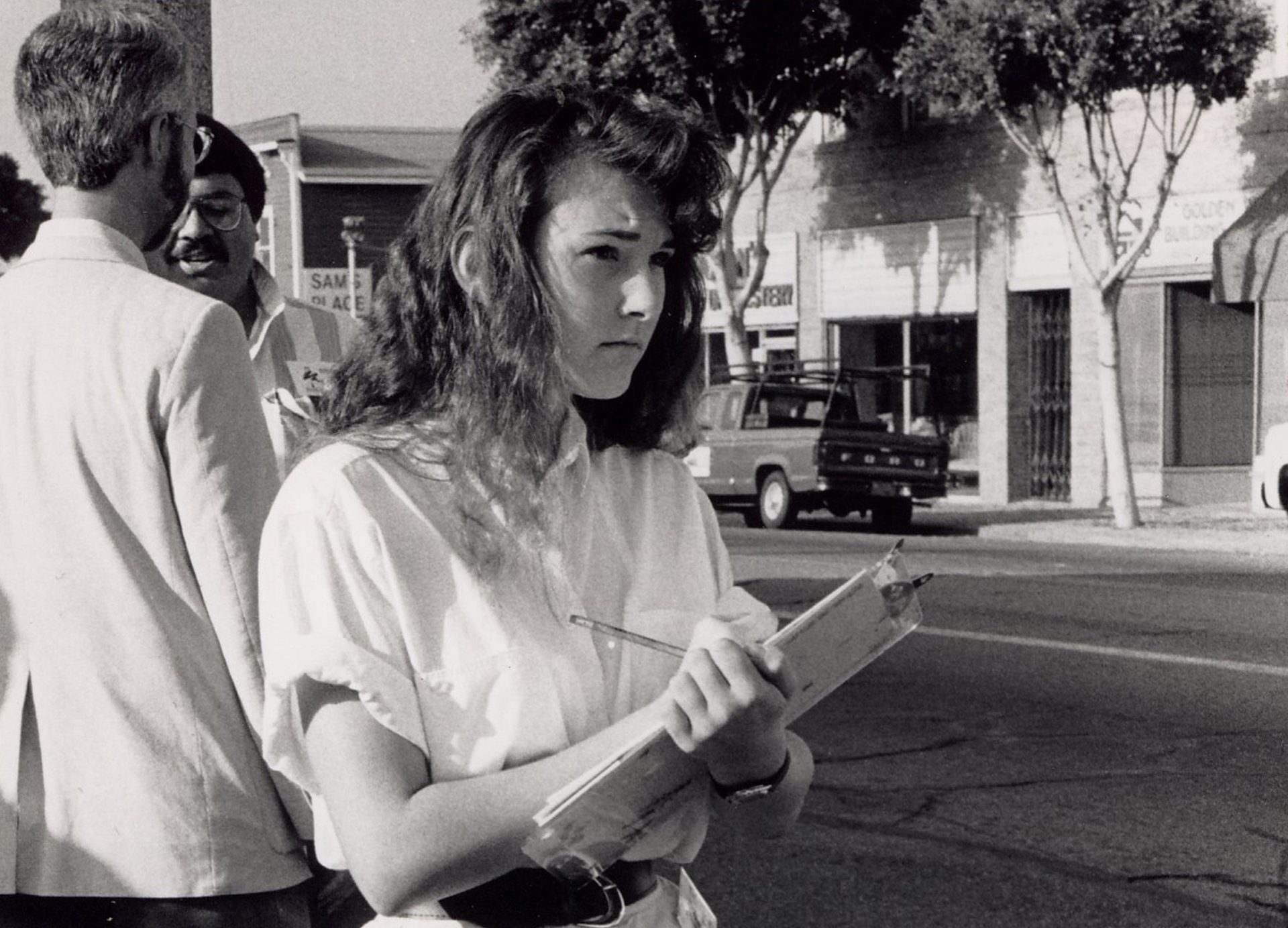

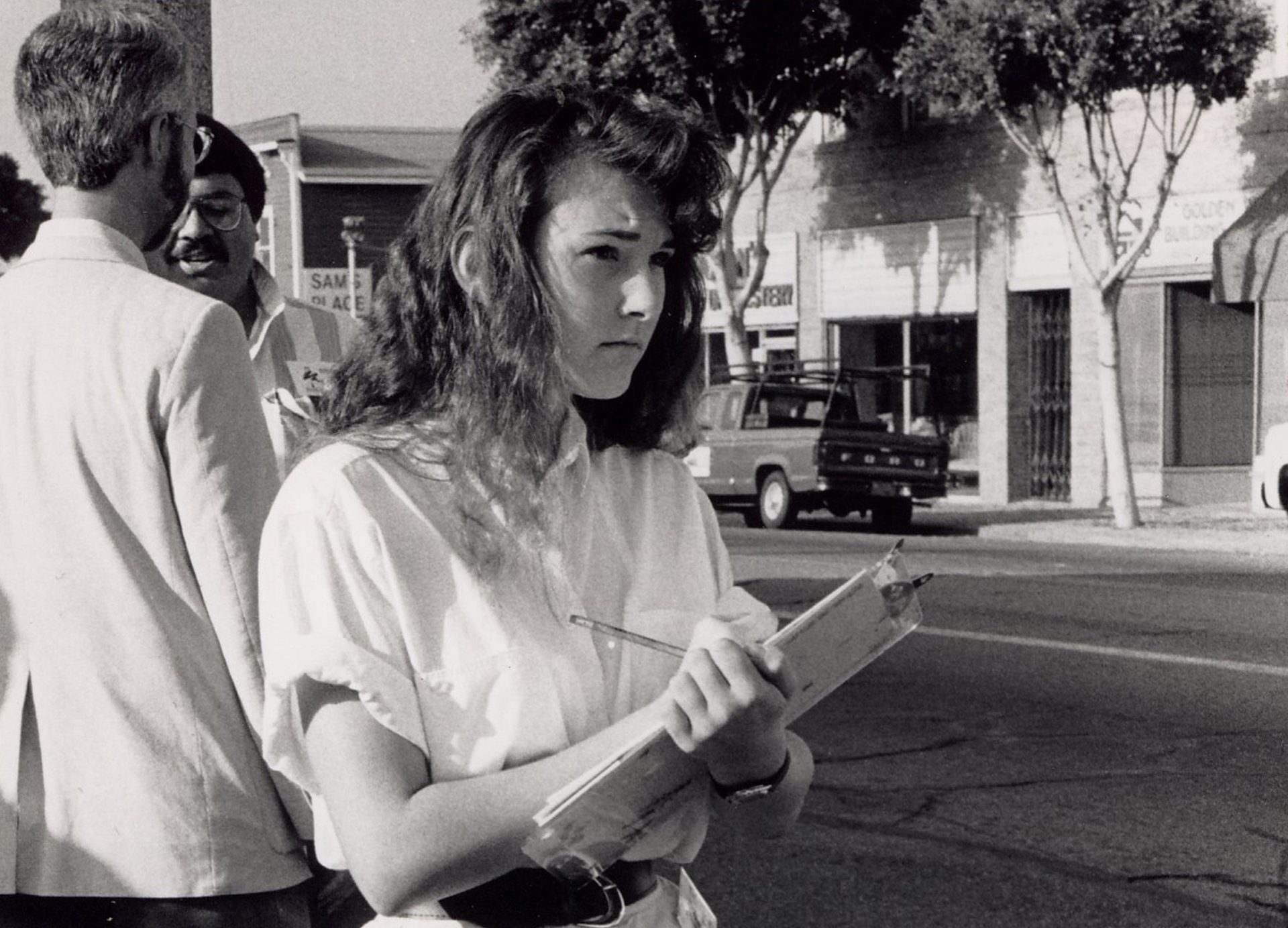

Hundreds of volunteers worked on the Downtown Redevelopment Charette. This woman is documenting visual observations of the downtown.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

Agriculture was Brea’s other major economic engine. Surrounded by more than 5,000 acres of citrus trees, Brea was promoted as the world’s largest orange grove. Before 1950, the citrus industry employed hundreds of immigrant workers. In successive waves, Chinese and Japanese immigrants worked in the groves until immigration restrictions and alien land lawsAlien land laws: Alien land laws refers to the practice of western states to limit ownership and later the leasing of agricultural land to Japanese immigrants. Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming all had laws or state constitutional amendments that restricted land ownership in this way. The laws were prominent from 1913 to 1952 when the US Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional. cut off their opportunities. Mexican American workers came to fill their places, recruited by growers who lobbied the California government for an open border policyOpen Border Policy: A border policy that allows for people and goods to travel across borders with little or no restrictions.. Segregated from White residents, Mexican farm laborers lived in citrus camps in the groves. In 1919, Orange County established segregated schools in the citrus camps for children of Mexican descent. Most of these schools ended by seventh or eighth grade and provided only a basic vocational education. In response to this blatant discrimination, five Mexican American families mounted a legal fight for equal education in Orange County. In 1946, led by Gonzalo and Sylvia Mendez, successful tenant farmersTenant farmers: Describes farm laborers who live on and work land they do not own. Tenant farmers pay rent to landowners either in the form of cash, crops, or a combination of the two. in Westminster, these families filed Mendez v. WestminsterMendez v. Westminster, 1946: Mendez et al v. Westminster School District of Orange County et al (1946) is an historic court case on racial segregation in the California public school system. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that it was unconstitutional and unlawful to forcibly segregate Mexican-American students by focusing on Mexican ancestry, skin color, and the Spanish language. This case forged a foundation upholding the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, thereby strengthening the landmark US Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which found racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. on behalf of 5,000 students. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit determined that this system of school segregation violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Eight years later, the case served as a precedent in Brown vs. Board of Education.Brown v. Board of Education, 1954: A US Supreme Court decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools and overturned the previous Court decision of “separate but equal” in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

By the late 1950s, oil production declined and housing boomed. Combined with post-war lending programs that favored new suburban construction built for Whites only, innovations like highways, air conditioning, and improved water systems made living in the southwest climate more appealing. Union Oil, the region’s largest landowner, pivoted to the lucrative business of residential development. In a single decade, the city quadrupled in size as it annexed property sold by Union Oil and other landholders. Following the template set decades prior, city planners turned newly cleared tracts into large single-family dwellings. Cashing in on the new market, realtors helped create exclusively White neighborhoods that perpetuated Brea’s established reputation for exclusion.

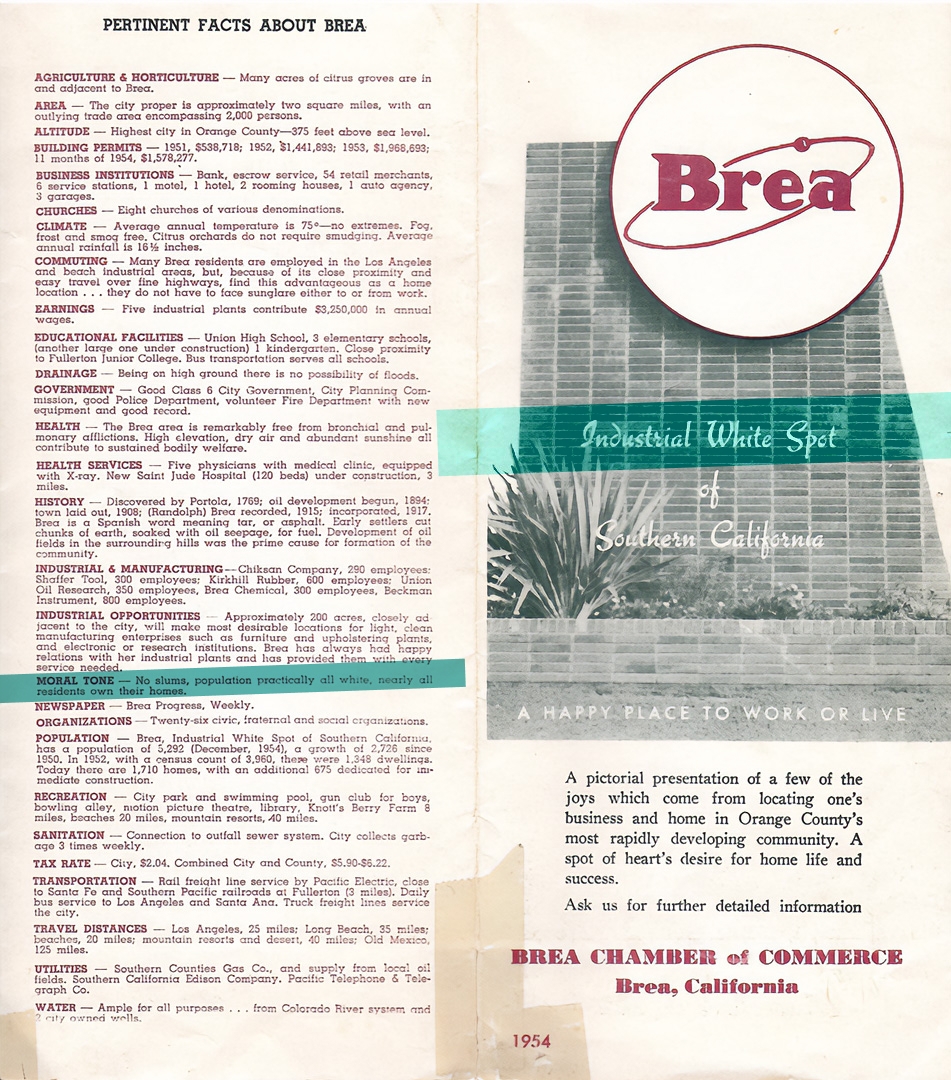

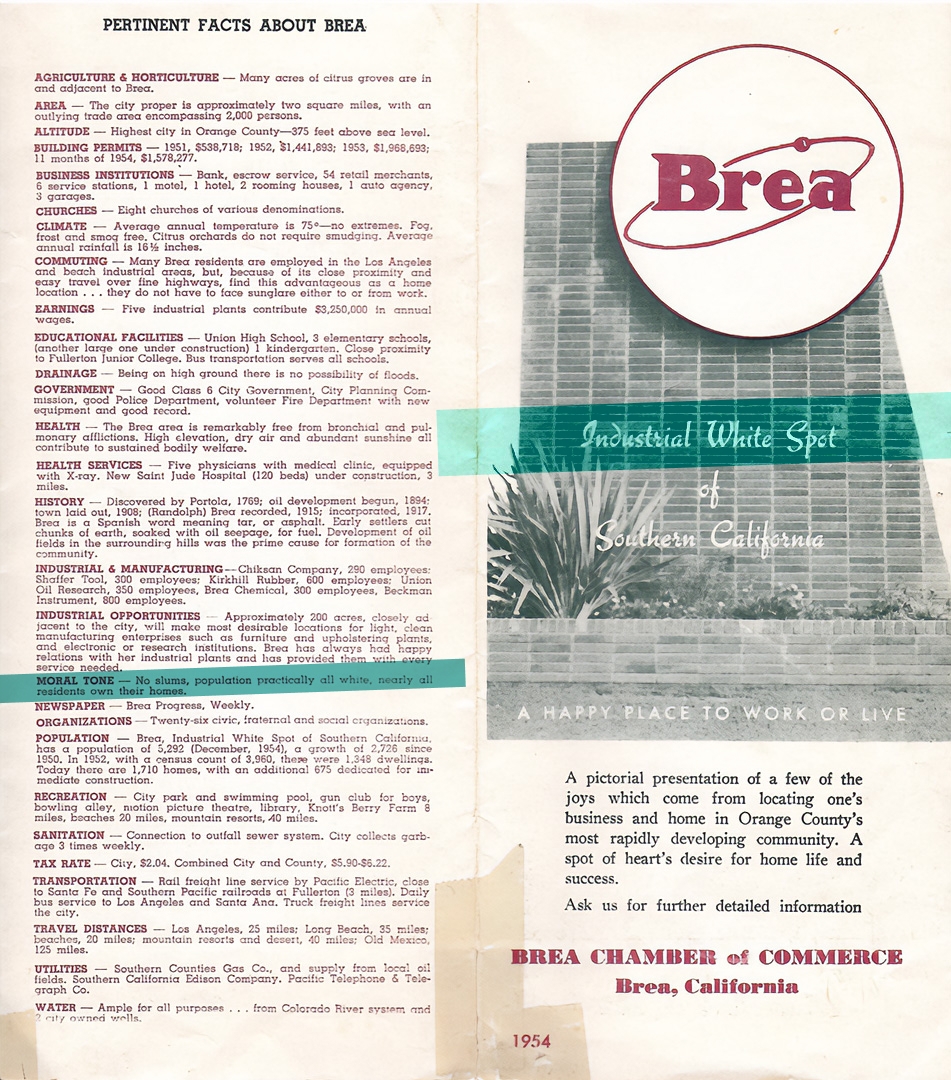

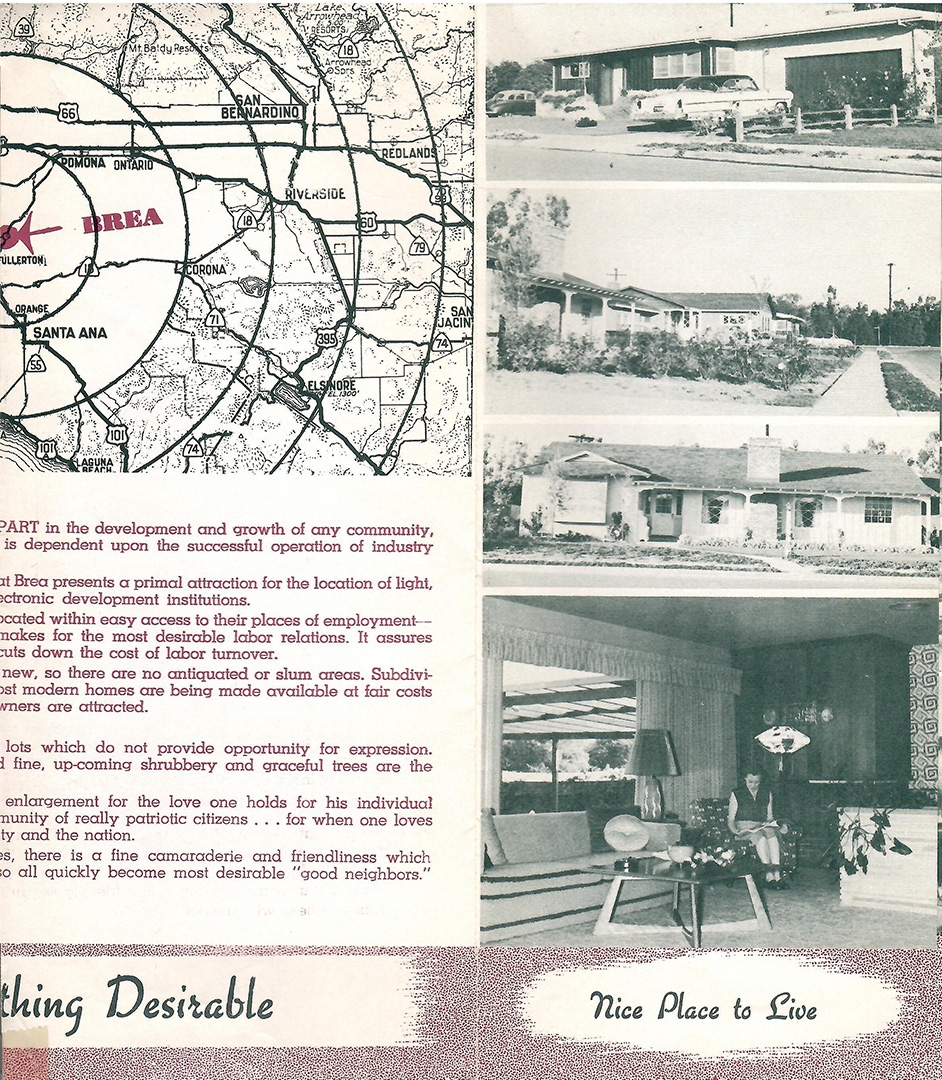

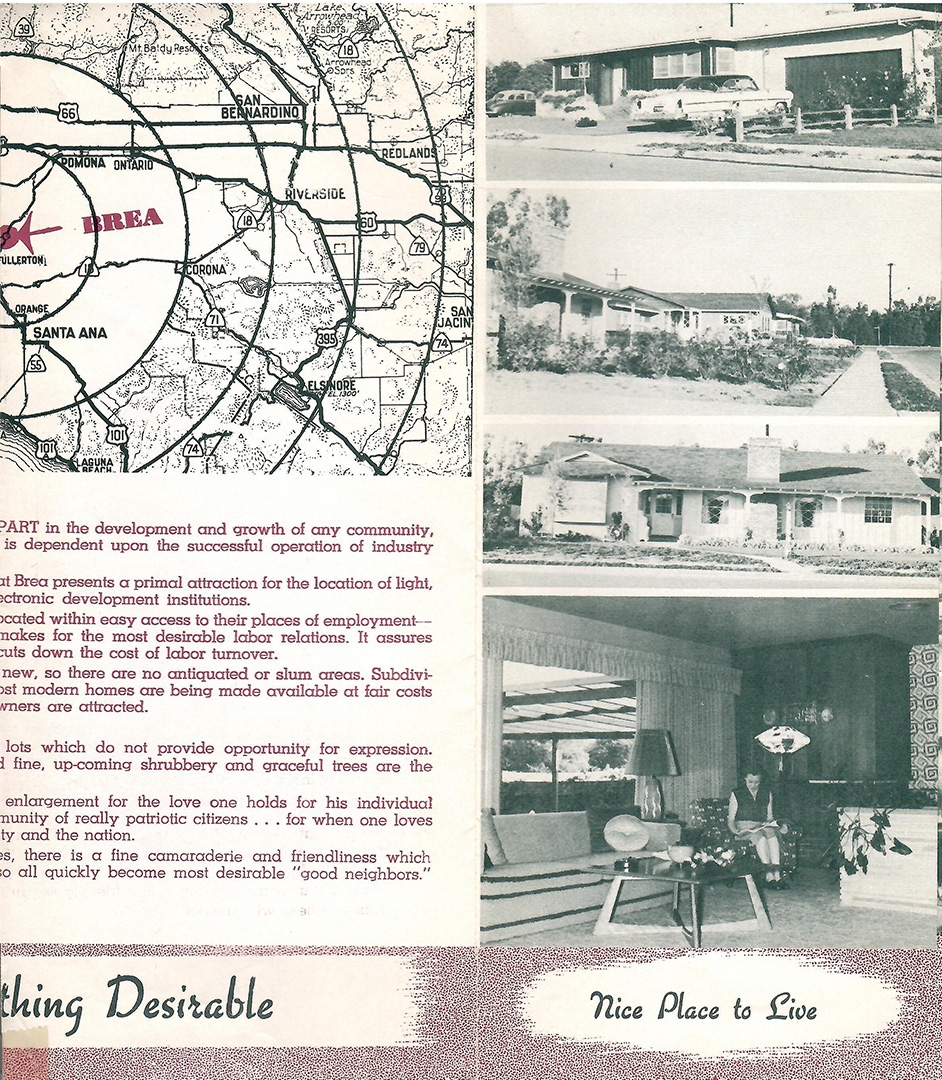

Already home to 23 industries, in 1954 Brea was promoted as Orange County’s most rapidly developing community. The Chamber of Commerce promoted the city to new and relocating businesses as “The Industrial White Spot of Southern California,” highlighting Brea’s “moral tone” with “no slums, population practically all white, nearly all residents own their homes.”

The Chamber of Commerce promoted the city to new and relocating businesses as “The Industrial White Spot of Southern California,” highlighting Brea’s “moral tone” with “no slums, population practically all white, nearly all residents own their homes.”

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

The Chamber of Commerce promoted the city to new and relocating businesses as “The Industrial White Spot of Southern California,” highlighting Brea’s “moral tone” with “no slums, population practically all white, nearly all residents own their homes.”

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

Like other California communities, Brea resisted attempts to end housing discrimination. Many residents joined the John Birch Society,John Birch Society: A right-wing political organization founded on anti-Communism and social conservatism. Established in 1958 by Robert W. Welch, Jr., a retired candy manufacturer, it rapidly grew in popularity during the 1960s. Supporters rejected the civil rights movement and often supported conspiracy theories. It remains active with national headquarters in Appleton, Wisconsin.

a nationwide group that opposed the civil rights movement with its perceived threat of communism. Orange County alone had 38 chapters with approximately 5,000 members. After Shelley v. KraemerShelley v. Kramer, 1948: A US Supreme Court decision that ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. It did not remove them from property deeds and many remain on deeds to this day. in 1948, the California Real Estate Association lobbied for an amendment to the state’s Constitution that allowed the use of restrictive covenants, arguing that it would protect property values. Realtors continued to discriminate. The 1963 Rumford Fair Housing Act,Rumford Fair Housing Act, 1963: The California Fair Housing Act of 1963 (Assembly Bill 1240) prohibited racial discrimination by property owners and landlords. Known as the Rumford Act for sponsor William Bryon Rumford, the first Black man from northern California to serve in the California legislature, it strengthened earlier fair housing laws in California. It was overturned by voters with Proposition 14 in 1964 and restored when the California Supreme Court ruled the ballot initiative was illegal in 1966. signed into law by the governor, attempted to end racial discrimination. In 1964, California voters passed Proposition 14Proposition 14- California, 1964: A ballot initiative for the California Constitution that nullified the Rumford Fair Housing Act passed in 1963. Passing with a vote of 65% approval, it established a state constitutional right for property owners to refuse to sell, lease, or rent residential properties to others. The California Supreme Court ruled in 1966 that it was unconstitutional as it violated the 14th Amendment Equal Protection Clause. to repeal the Rumford Act to continue discriminatory practices. Voters in Brea overwhelmingly supported Proposition 14.

A photograph of 123 S Madrona. Built 1914, one of the 193 homes removed for downtown redevelopment.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

The 57 Freeway opened in 1972, making Brea more accessible to the rest of the county. The opening of the Brea Mall in 1977 brought increased tax revenues, propelling the community to a higher level of wealth and exclusivity. Major suburban developments east of the 57 Freeway were completed from the 1980s to the 2000s. The success of the Brea Mall pulled business from the downtown and caused fears of decline. Pressure built to redevelop the area. Despite attempts to bring multiple voices to the planning, the downtown redevelopmentRedevelopment: The process of constructing new structures in an urban area. This often involves replacing existing buildings and displacing the original inhabitants. polarized the community.

The success of the Brea Mall pulled business from the downtown and caused fears of decline.

The completed mall turned downtown into a ghost town as shoppers were no longer satisfied with old small retail shops with small inconveniently placed parking lots. Redevelopment would become inevitable.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

Many in Brea argued that redevelopment was a much-needed jolt that would keep the city alive. Others believed it was the Council’s attempt to expel the Mexican population. In the end, the City used eminent domain to demolish 48 properties for new construction and wider roadways. Dozens of business owners, including William Vega and Daniel Cesario, pleaded with city officials to halt the redevelopment—to no avail. Vega sued the city to prevent the seizure of his mother’s property. When that did not work, he twice ran for Brea City Council.

Volunteers spent countless hours discussing the ideas and visions for the new downtown. Meetings like this lasted hours.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) halted redevelopment plans while Brea was under investigation for misappropriation of federal funds. Despite the scandals and controversy, redevelopment picked up exactly as planned, eventually razing 193 homes and displacing 400 low-income people. Redevelopment included little low-income housing, leading to charges that Brea was hoping to eliminate poor people from the community.

Looking like a ghost town, during the 1990s, Brea businesses are boarded up awaiting demolition during redevelopment.

Courtesy of the Brea Historical Society

Today, the city is home to almost 44,000 residents but draws on the skills of more than 60,000 workers, many of whom cannot afford to live in Brea. Many long-time residents lament they cannot afford to re-buy their home at its current market value. The City formally participates in the Fair Housing Council of Orange County, through the Orange County Urban County Program. The Council provides services throughout the Urban County area, including Brea, to ensure equal access to housing. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Brea’s residential population has grown more diverse. According to the 2019 American Community Survey, Brea is 42% non-Hispanic White, 32% Hispanic or Latino, 22% Asian, and 2% Black or African American. The specific housing vision established more than half a century ago put Brea beyond the reach of many, requiring at least an upper-middle-class income. Brea’s legacies as an oil boomtown, sundown town, agricultural production community, and exclusive suburb are still visible in its patterns of living.