Article 14

Did anyone win the fight for fair housing?

Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives

How would you define fair housing?

Prior to 1968, could you buy, rent, or live in a house in your community?

How can you be sure a fight has been won?

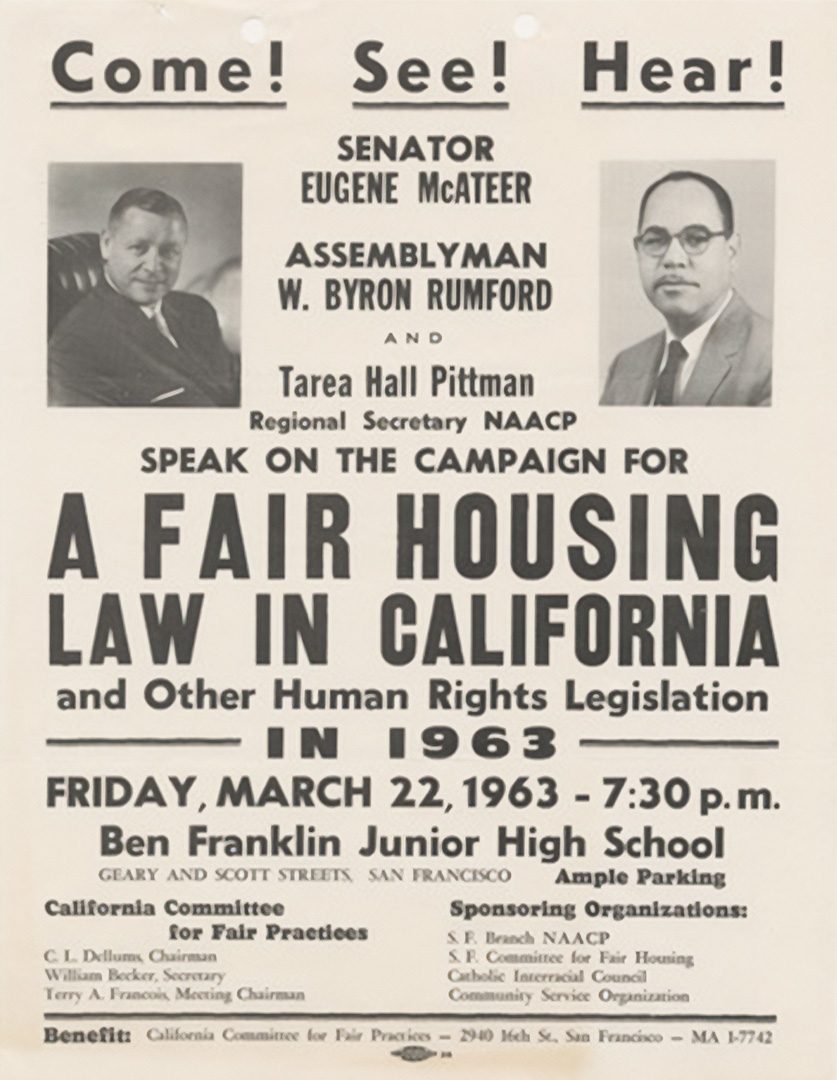

A 1963 flyer for presentations on the campaign for a fair housing law in California sponsored by the San Francisco branch of the NAACP and others.

Courtesy of the Bancroft Library

The Fair Housing Act was designed to end housing discrimination and reverse housing segregation. After it was passed in 1968, it was no longer legal for bankers to deny loans to borrowers of color or refuse to show houses to clients of color. Racially restrictive covenants were struck down too. The Act directed the government to “affirmatively further” fair housing. But today, more than 50 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, its goals have still not been fully realized.

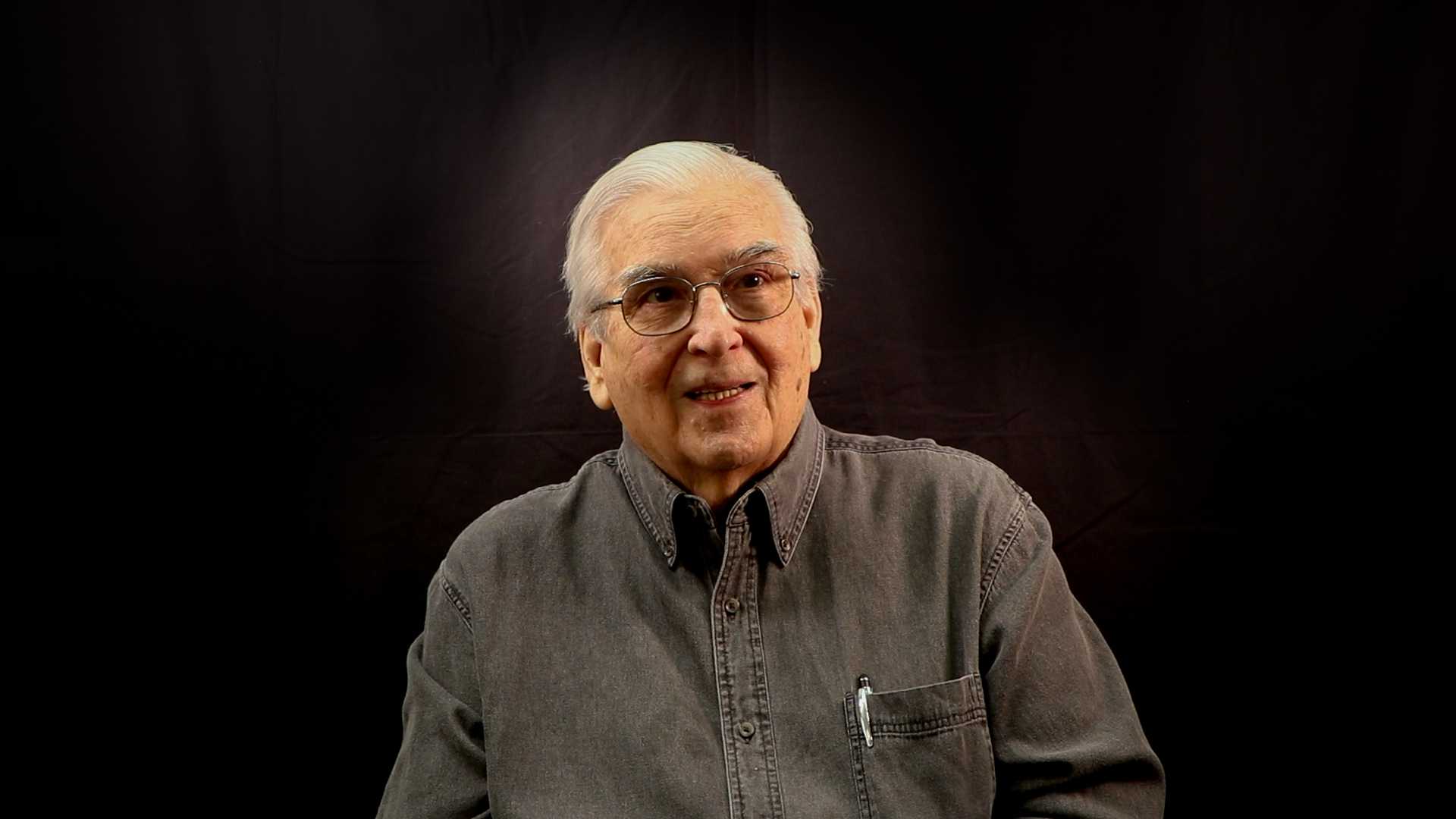

We were also able to work with the REALTOR® association. And I think at some point fairly early on, they began to see the mistakes that were made in the past.

Civil Rights Activist

ViewHide Transcript

Hope was involved in litigation against the REALTORS®. But we also, as time went on, we were also able to work with the REALTOR® association. And I think at some point fairly early on, they began to see the mistakes that were made in the past and so there were a couple REALTORS® especially, that we worked closely with and one of whom is still a very good friend of mine. In fact, I heard from him this morning. So, you know, Hope was hated by many people. I was hated by many people. I received death threats and all of that. But also a lot of people believed in what we did, supported us, and whether they're REALTORS® or not or they realize that what we're trying to accomplish was the right thing.

I think initially there were some people, especially in politics, that felt that fair housing was just an attempt to move Black people to the suburbs. We were not in the moving business. We simply represented those who wanted to move out here because of schools, because of housing, good housing, because of the parks and open space, because of health care. They wanted to move out here also, many worked out here and were commuting each day back to the city. And that's why, they like everybody else that moved out here, moved out here for a reason, and it had nothing to do with race. And so, that was our job, just to, if someone had a right to move and that's what they wanted to do. We made sure that they were able to do that.

For all its ambition, the Fair Housing Act never defined fair housing. The Fair Housing Act opened neighborhoods to people of color who could afford them. But it did nothing to change the underlying wealth inequality that kept many people from affording those homes. White homeowners could use their greater wealth and access to credit to opt out of integration by moving to even more segregated areas. In 1971, White residents of Warren, Michigan, rose up against the governor’s plan to develop affordable housing there. The backlash led to a visit from President Richard Nixon, who said that “forced integration of the suburbs is not in the national interest.” The often negative perception of the Fair Housing Act among suburban homeowners created an ongoing political and social struggle. Because of this intense pushback, the Fair Housing Act rarely accomplished the goals laid out in legislation.

Patricia R. Harris was the first Black woman to serve in the U.S. Cabinet when President Jimmy Carter selected her to be secretary of Housing and Urban Development in 1977. While in that position, she shifted the agency away from tearing down slum housing to rebuilding and rehabilitating neighborhoods.

Courtesy of the Office of the Department of Housing and Urban Development

Resource

The gap between White and Black homeownership is larger in 2018 than 1960. A Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting segment.

Housing discrimination is still happening. It is estimated that almost four million acts of housing discrimination take place each year in the U.S. In 2020, 28,712 fair housing complaints were filed. And when sellers or lenders break the law, people who are denied fair housing have to pay the legal costs of seeking justice.

Access to home loans is still unequal. From 2012-2018, Chase Bank made more loans in one single White-majority neighborhood (Lake View) than all Chicago neighborhoods of color combined. Less than 2% of the $7.5 billion in loans went to Black neighborhoods. A 2019 study found that Black mortgage applicants in Chicago were 150% more likely to be denied than White ones. Another study of two million mortgages across the U.S. found that compared to similar White applicants, banks were 40% more likely to deny a Latino applicant, 50% more likely to deny an Asian/Pacific Islander applicant, 70% more likely to deny a Native American applicant and 80% more likely to deny a Black applicant.

Resource

A June 2018 PBS NewsHour story on Portland's Right to Return program.

The Act’s provisions have also been twisted by exploitative lenders. A harmful practice known as reverse redlining helped to spark the 2008 banking crisis. Reverse redlining targets first-time minority buyers with offers of high-risk mortgages. Wealthy Black homebuyers were two times more likely to be offered subprime mortgages than working-class Whites.

The Fair Housing Act was both a major victory for the Civil Rights Movement and a result of compromise by office-holders eager to move on from the turbulence of the 1960s. More than 50 years after the Act was passed, the US is still highly segregated. Today, too many Americans are confined to substandard housing, locked out of home ownership, paying exploitive rents, forced out by eviction, or struggling to find places to live at all. Much work remains to be done.

Additional Resources

The gap between White and Black homeownership is larger in 2018 than 1960. A Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting segment.

A June 2018 PBS NewsHour story on Portland's Right to Return program.