Article 4

Sundown Towns, the KKK, and the Ever-Present Threat of White Violence

Courtesy of Ball State University

Hate Segregates the Nation

ViewHide Transcript

White supremacy and violence helped sustain segregation in American neighborhoods.

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan became a major force in upholding white domination and enforcing sundown practices. During this time the KKK was at its most powerful. The Klan drew millions of members not only from the South, but from the North and West. Nearly 45% of Klansmen lived in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio alone.

The new KKK did not just target Black people. Klan leaders hired public relations experts to help broaden their reach. They sold tailored messages to different areas, rallying Klan members and their families against Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and other minorities.

These rebranding efforts were a success. Police officers, judges, and elected officials openly flocked to its ranks, giving the group a veneer of respectability and lawfulness.

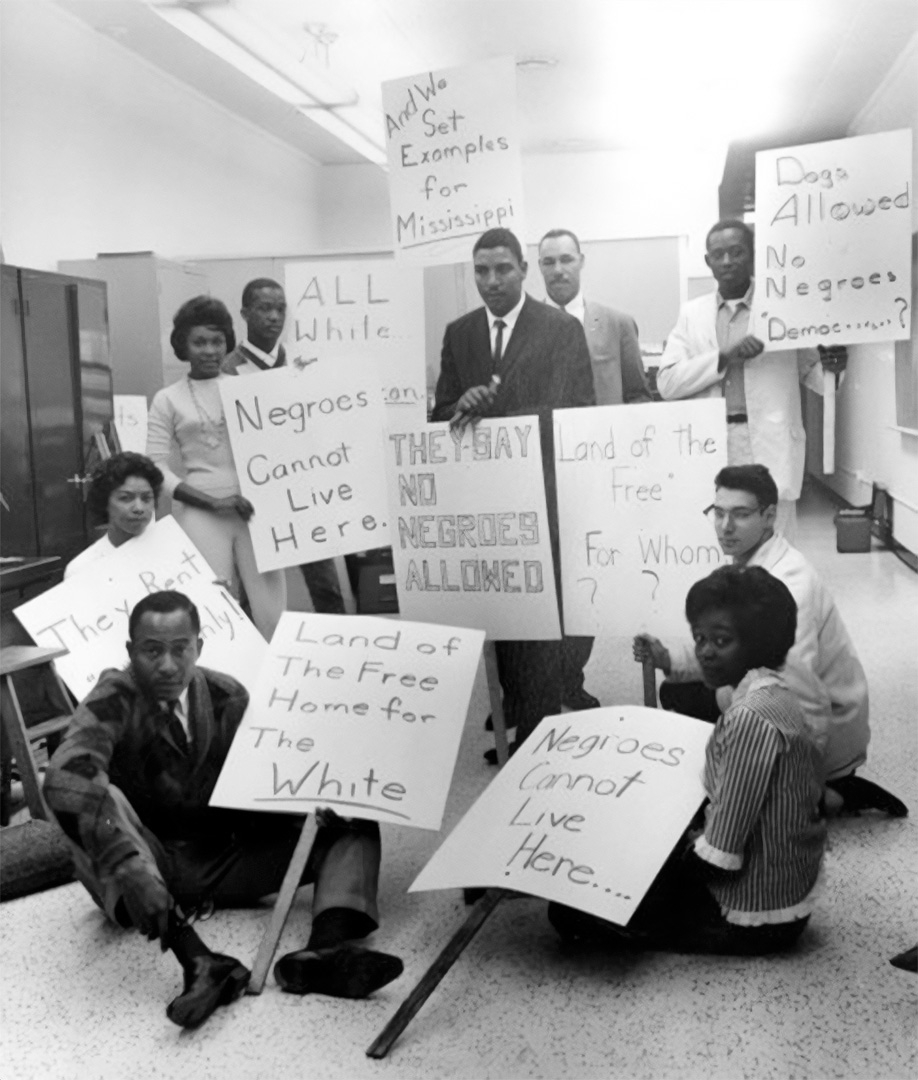

Sundown towns were another key example of white supremacist tactics. Beginning in the late-nineteenth century, these all-White communities excluded Black people and other minority groups by custom or through laws and threats of violence.

The name comes from the practice of allowing people of color to work in a community as household staff, day laborers, or as hired hands in factories or agriculture. Despite being allowed to work in the town by day, they were forced to leave by sundown.

Some towns had warning sirens or signs posted at their borders, telling people of color to leave by sundown. Often, the rules were unspoken but widely known. Most sundown towns had no official signs or ordinances on the books, but all knew who was welcome…and who was not.

During the Great Migration and periods of increased immigration, many White communities in the North and West rallied with the KKK to preserve their neighborhoods against the perceived threat of racial minorities.

They organized neighborhood associations, targeting Black newcomers and others they deemed unacceptable with tactics ranging from subtle social pressures to outright mob violence.

Between 1917 and 1921, at least fifty-eight Black-owned properties in Chicago were firebombed.

In 1951, a mob of thousands attacked the home of a single Black family in an all-White Chicago suburb, Cicero. They threw lit torches through windows and smashed their furniture to pieces, causing $20,000 of property damage.

But Black people did not simply accept white supremacist violence and attacks on their homes. They attempted to defend their families and homes, and in rare cases were successful in court.

In 1925, Dr. Ossian and Gladys Sweet realized their dream of homeownership and purchased a home in an all-White neighborhood in Detroit.

When a white mob attacked the building, shots were fired from inside, and a man was killed. Sweet and his friends were charged with murder.

When the case went to trial, the NAACP and well-known lawyer Clarence Darrow defended Dr. Sweet—and won.

For many Black Americans, the Sweet case proved that Black people also had the right to defend their lives and their property.

It was just one example of countless acts of resistance to white supremacy, violence, and hatred.

Have you ever felt afraid in your own neighborhood? What caused your fear?

Have you ever been afraid in someone else’s neighborhood?

Have you ever decided not to go somewhere to protect your own safety?

Violence reinforced segregation. For Americans of color up through the early 1900s, violent acts and the threat of violence kept behavior under tight control and limited the freedom to move.

Anti-Asian violence drove Chinese people out of many towns in the West. In 1885, an armed mob of White miners attacked a Chinese neighborhood in Rock Springs, Wyoming. The rioters killed 35 people, wounded 15, and drove more than 700 others from town before burning their buildings. Continuing violence and persecution eventually drove most remaining Chinese people from the state. In 1870, Chinese Americans made up one third of Idaho’s population. By 1910, that number was near zero.

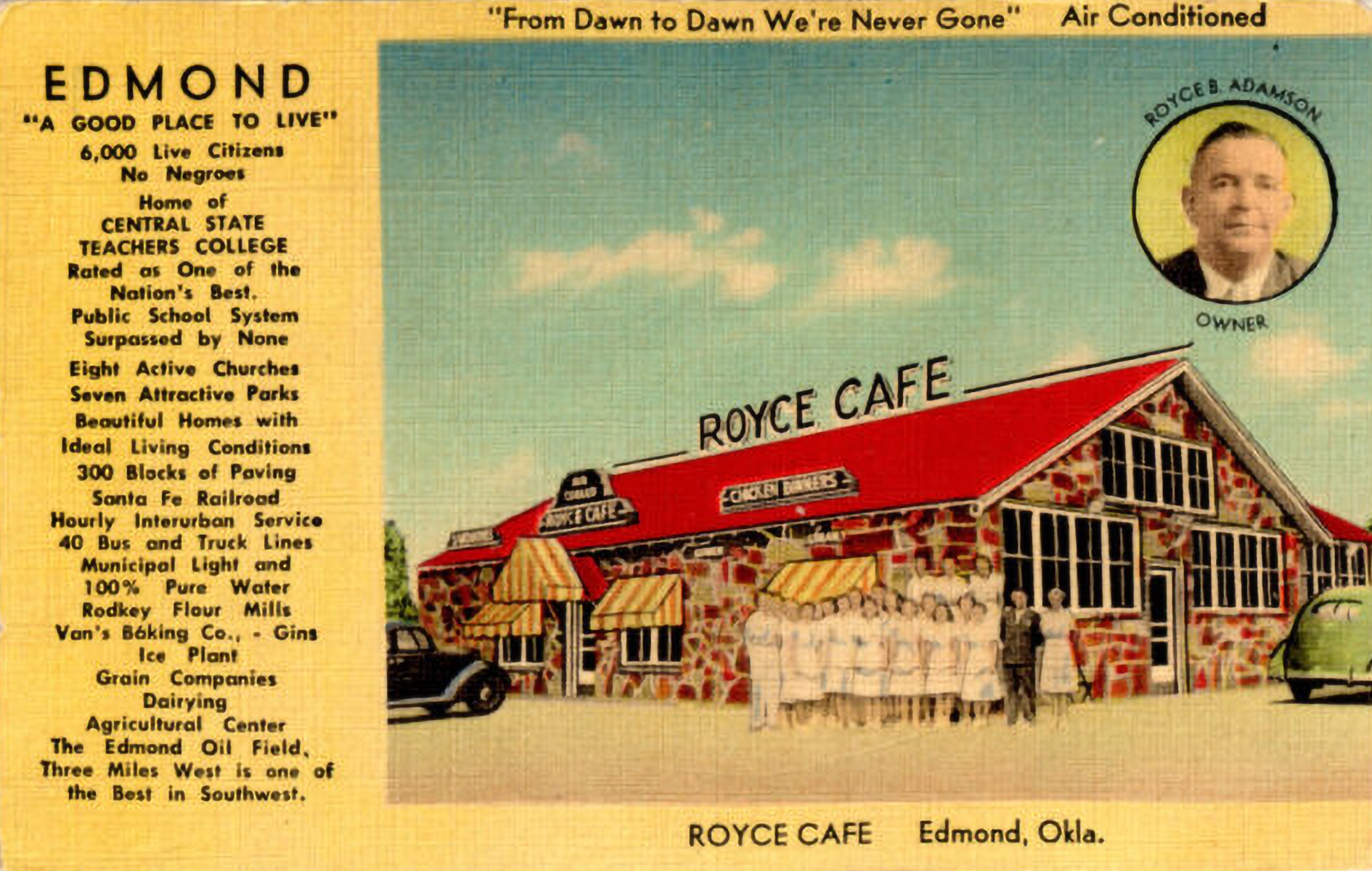

Edmond newspapers described the Oklahoma town as 100% White in the 1920s. Local businesses like the Royce Cafe, one of Edmond's most popular restaurants from the 1930s until 1970, also included this message in their marketing.

Courtesy of the Edmond Historical Society and Museum

In the summer of 1919, violence broke out across America. In what became known as the Red Summer, White mobs attacked Black communities in dozens of cities and rural towns. Chicago saw one of the worst outbursts with simmering tensions over housing, jobs, and policing igniting into five days of violence —leading to the deaths of 23 Black residents and 15 White residents.

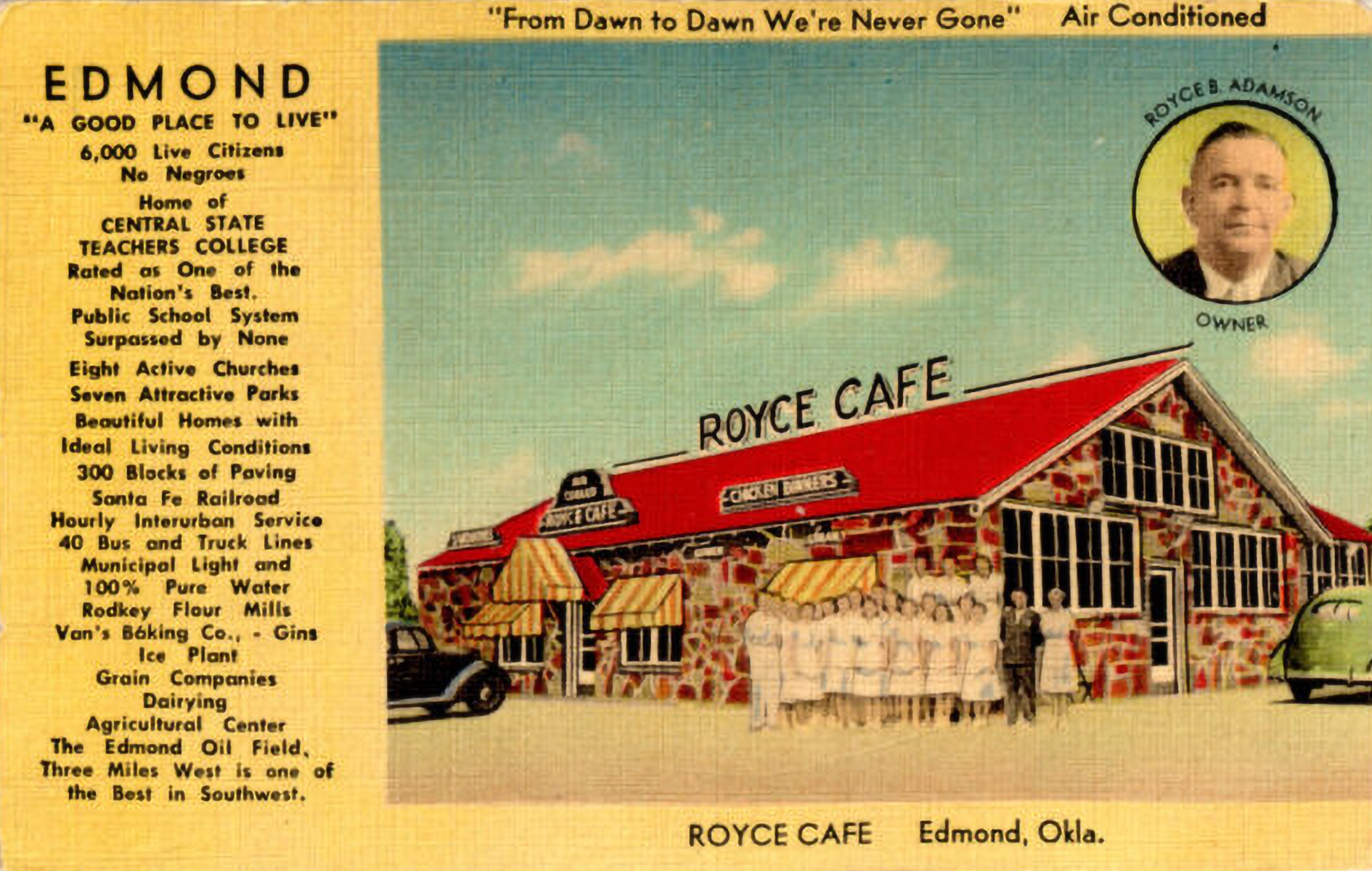

The Colored Women's Clubs of Michigan released their “Red Record” in 1922 that detailed the national crisis of lynching and called out northern legislators who voted against the bill.

Representative Leonides Dyer (R-MO) introduced anti-lynching legislation in 1918. His bill passed the House but was defeated by a Senate filibuster by Southern Democrats. In 2021, the Emmett Till Anti-lynching bill passed in the House and failed to pass in the Senate. After over 200 attempts since 1900 to pass anti-lynching legislation, this bill finally passed both Chambers and was signed into law by President Biden in 2022.

Courtesy of the National Archives

In 1921, a White mob looted the Greenwood District in Tulsa. They destroyed thirty-five square blocks, including a thriving business area known as Black Wall Street, and killing about 300 people. Residents of the area filed almost 200 lawsuits against the city and insurance companies but were unsuccessful in getting compensation for damages.

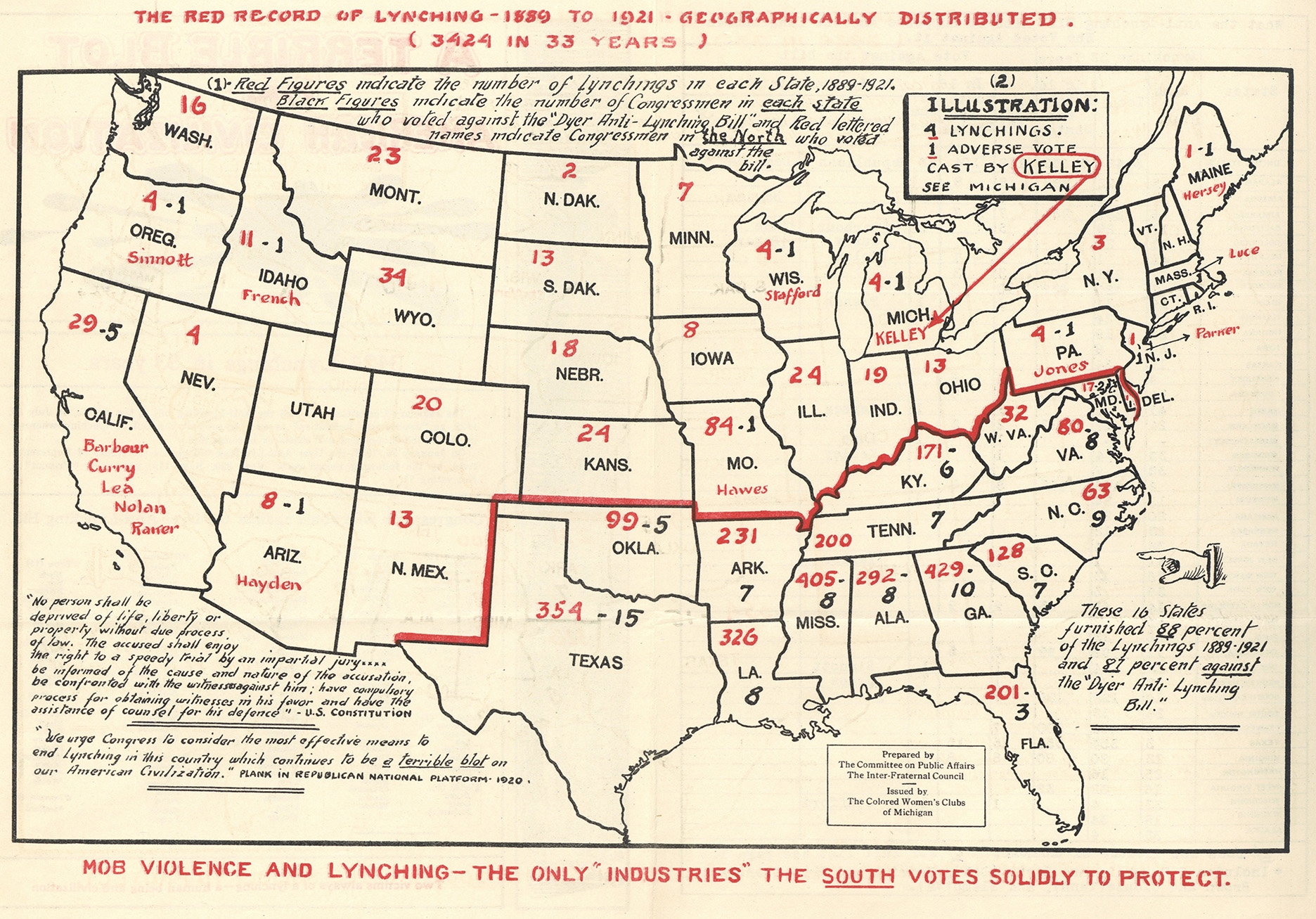

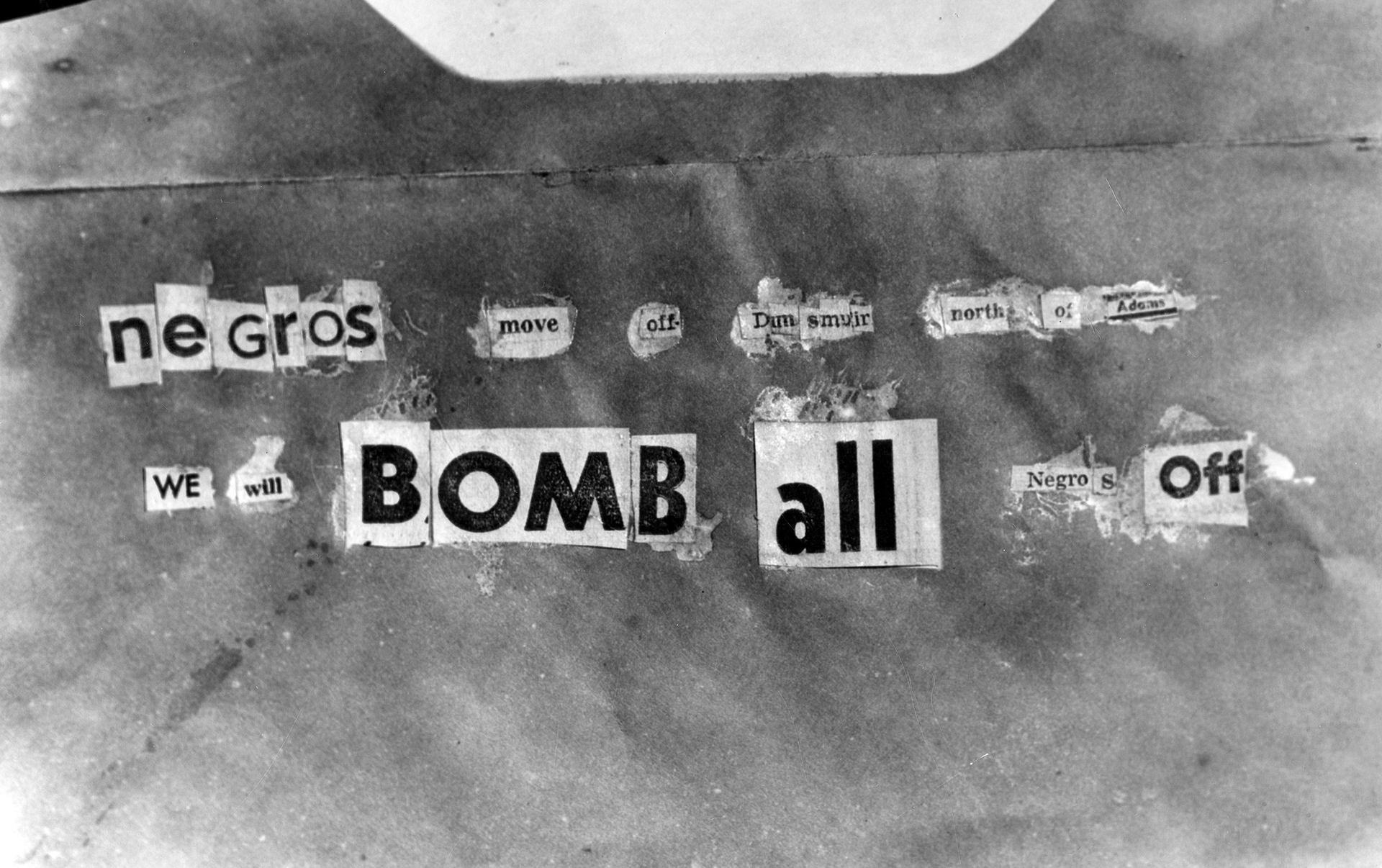

Photograph of bomb threat found at William Bailey's house in Los Angeles, taken in March 1952.

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library

Some White communities reached for an old tool from the Reconstruction era:Reconstruction era: Immediately following the Civil War, Reconstruction (1865-1877) was the United States’ effort to reincorporate federally occupied southern states and integrate four million newly emancipated Black Americans into civic life. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments (known collectively as the Reconstruction Amendments) abolished slavery, granted equal protection, and the right to vote to Black men. Southern governments responded with Black Codes and many whites embraced white supremacist violence against newly freed people. After Reconstruction removed federal oversight, many states instituted Jim Crow laws and segregation. an organization known as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Once a loosely affiliated paramilitary group, the KKK conducted raids on Black communities until 1871, when the government deemed it a terrorist organization. This effectively ended Klan activities through federal force. But in the 1920s, a revived and rebranded KKK and Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) brought up to five million men and half a million women into their ranks. Most were native-born White mainstream Protestants. The KKK reached far beyond the South; almost 45% of members lived in Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana. The Klan actively courted membership from police officers, judges, ministers, and elected officials, linking its brutal and murderous acts with the power of law. They presented themselves as patriotic friends to the White community with folksy, familiar activities like potluck dinners, parades, and gifts to the poor.

The new KKK and WKKK expanded the targets of their hate to include Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and others they considered enemies.

In 1925, 30,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan marched in segregated Washington, DC. The next year hosted 15,000 marchers. Many marchers revealed their face with no fear of legal consequences for the group's terrorism and murder.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The new KKK and WKKK expanded the targets of their hate to include Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and others they considered enemies. They used a range of tactics, from assault and lynchingLynching: The act of lynching is a mob of people murdering a person outside the boundaries of the law and always in a violent way such as hanging. Lynching is most commonly associated with the killing of Black people by White people in the United States especially in, but not limited to, the Jim Crow South. to cross burnings, intimidation, rumor, and slander. High-visibility rallies brought hundreds of White residents out for shows of force. In the 1920s and 30s, Klan rallies in Washington State incited mobs to evict Filipino and Japanese farmers who had skirted the state’s alien land lawsAlien land laws: Alien land laws refers to the practice of western states to limit ownership and later the leasing of agricultural land to Japanese immigrants. Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming all had laws or state constitutional amendments that restricted land ownership in this way. The laws were prominent from 1913 to 1952 when the US Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional. by buying farmland from the Yakama Nation Reservation. Mobs terrorized the farmers with beatings, arson, and dynamite, destroying their cars and buildings.

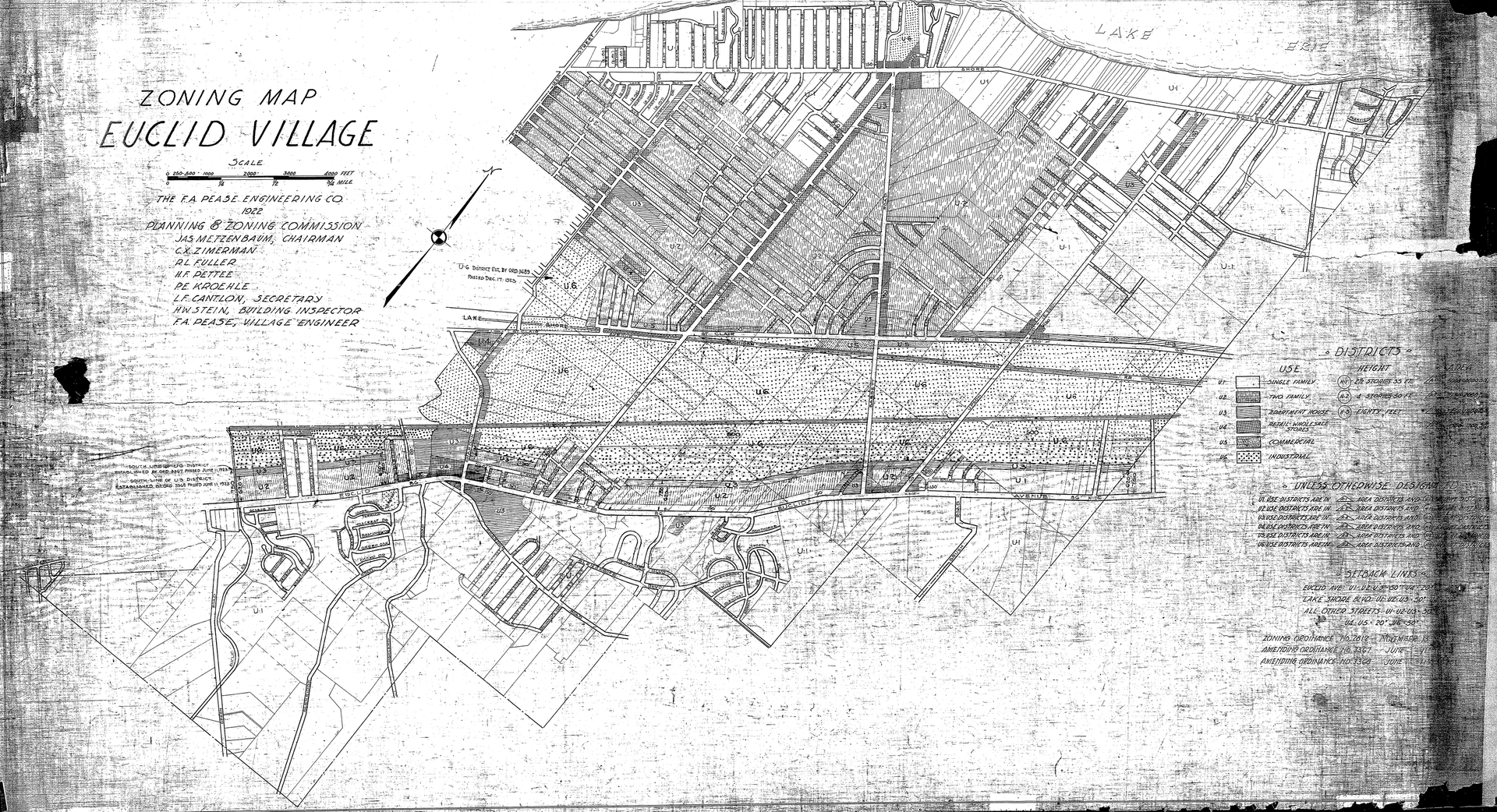

Sundown townsSundown Towns: All-white communities or counties that purposefully maintained their status through harassment, discriminatory laws and ordinances, and violence or threat of violence. The name comes from posted and verbal warnings that Black people and other people of color would receive upon entry. Sometimes this status was codified in law and signaled with signs, sirens, or other warnings. Often, laborers such as household, farm or factory help could work in a community during daylight hours and had to leave town by sundown. Frequently, it was maintained by practice and custom of local people and law enforcement. Sundown towns appeared in many areas of the nation between 1890 and the 1970s with some still maintaining their all-White status. were another tactic for maintaining White dominance. A sundown town made it clear that any Blacks and other people of color needed to leave town every day before dark or face dire consequences. Residents could rely on the labor of minority workers during the day but prevent them from moving in and gaining political power.

You knew where you did or did not want to be after dark.

Cultural Advisor

ViewHide Transcript

And so, in the context of sundown towns as a term. It wasn't something that was regularly used. So when you're trying to say, you know, where's the sundown town? Or why was that a sundown town? It may not have been the term you used. The term that may have been used was, “you don't want to be there after dark.” Someone later shortens it and calls it a sundown town. You knew where you did or did not want to be after dark.

In the story I told about Culver City. It was in the early evening and we were headed towards the wrong side of town in the eyes of this Culver City policeman. And we didn't have any business headed in that side of town. We didn't think that kind of thing was still alive. But we knew the history of it. And so a sundown town is almost impossible to define because it probably has more than one meaning. It may mean it's a sundown town because you just don't want to be in that part of town after dark, versus because of the kind of element that's in that part of town.

The other maybe it's a sundown town, because we don't want you to live here. We don't want to live with you. We may want you to work here, but we don't want you to live here. And so, therefore, we're not going to sell to you here. But it may also be because you can't buy here because you can't afford it, or no one will give you the land, or we're going to take the land. There's so many ways that a place can become a sundown town in the way we define it today.

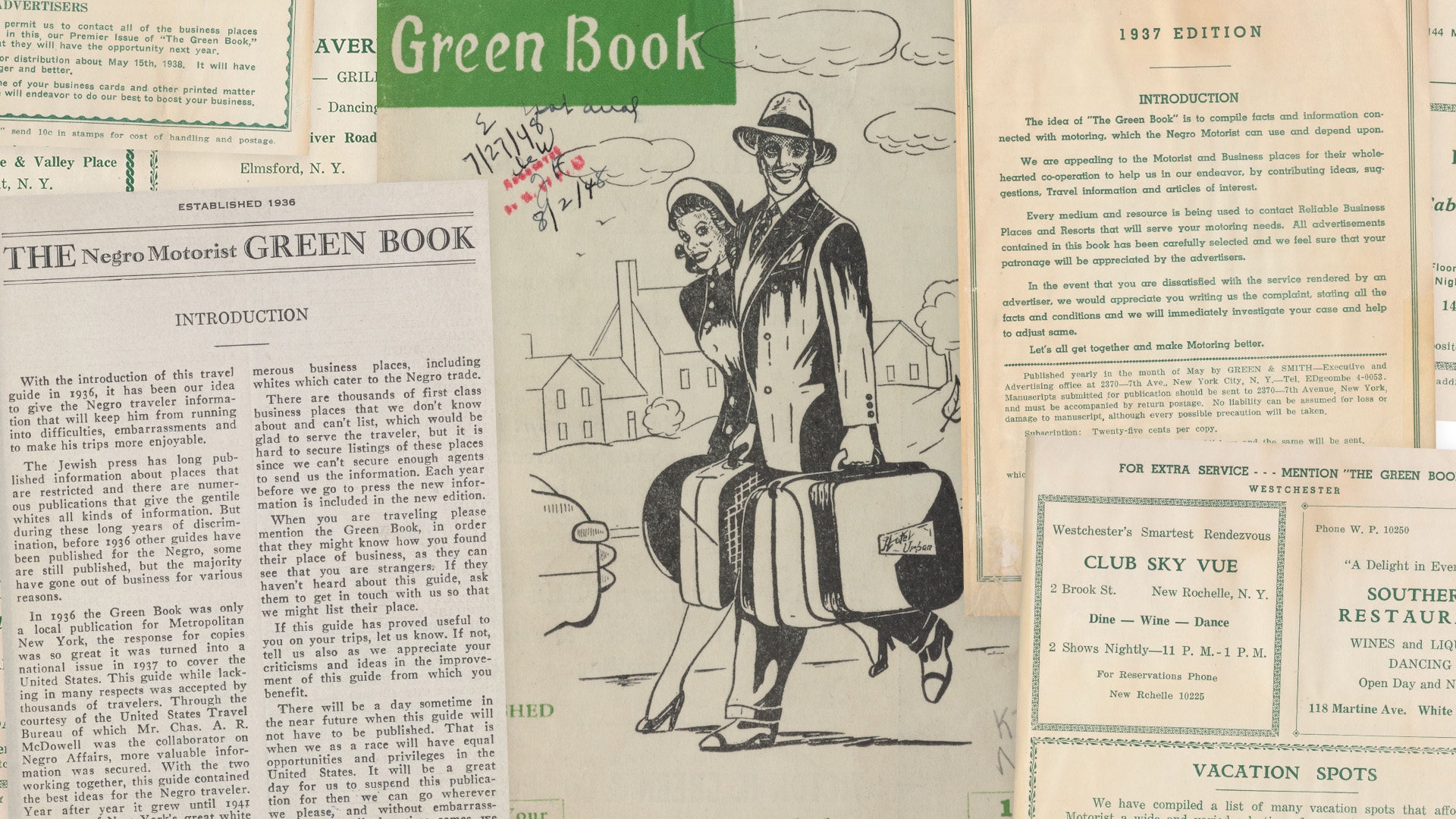

By the late 1800s, sundown towns across the North and West targeted Blacks and sometimes Latino, Native American, Asian, Jewish, and other groups. Some sundown towns signaled their status with threatening signs at the town line or a loud siren at sunset. More often, sundown policies were unwritten and unspoken, but keenly understood. The threat of violence was always present.

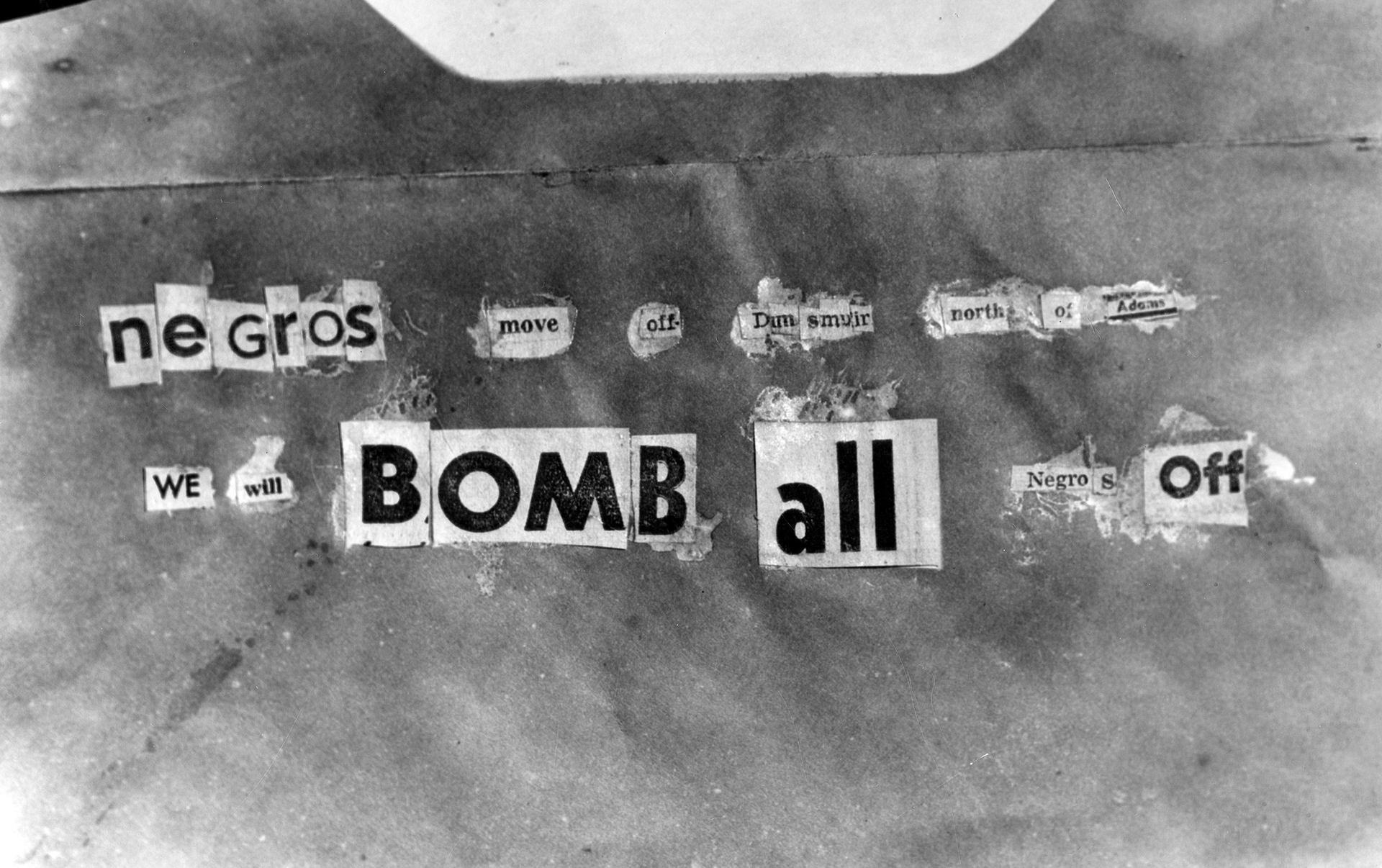

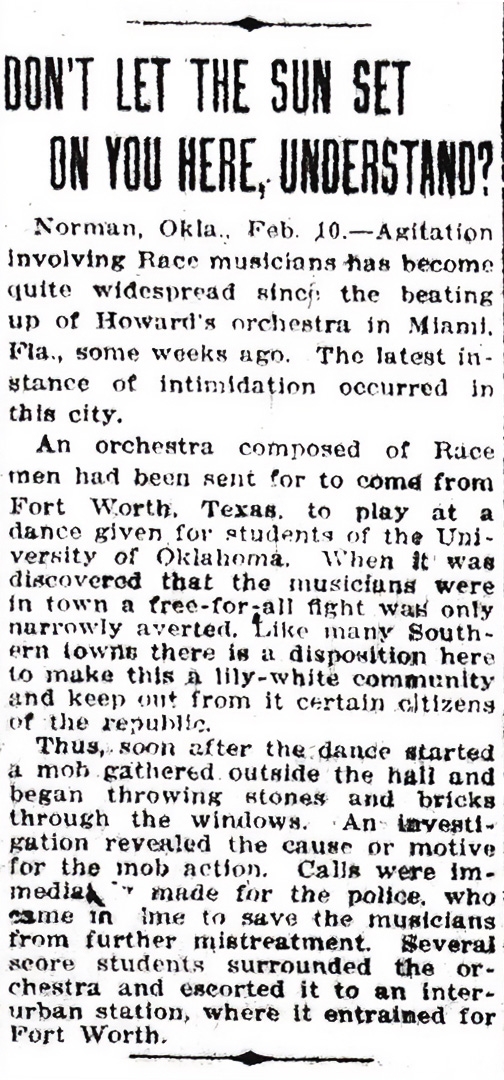

This headline reflects a common warning in sundown towns - "Don't Let the Sun Set on You Here." Sometimes this warning appeared on signs at the edge of city limits or heard through sirens sounding a warning for people to leave town. Sometimes it was spoken or unspoken by townspeople. This threat was directed at Black Americans and other people of color based on local prejudices.

Courtesy of the Chicago Defender

Neighborhood defenseNeighborhood Defense: Organizations founded by residents of all-White neighborhoods or communities designed to maintain segregation in their community. They used tactics ranging from intimidation of potential new residents to mob action and physical violence to people attempting to integrate neighborhoods and firebombing of homes. organizations also used the threat of violence to keep Black people out. Organized by White communities to fight integration, these groups used tactics ranging from social pressure to terrorism.Terrorism: The use of violence, particularly against civilians, to achieve a political goal. Between 1917 and 1921, white supremacists in Chicago firebombed the homes of at least 58 Black families, bankers, and real estate agents. In 1951, a White building owner in Cicero (a suburb of Chicago) rented an apartment to a Black World War II veteran and his family, ignoring the objections of local White racists. On the night the family moved in, a mob of more than 4,000 White people laid siege to the building. They threw bricks, rocks, and burning wood through the windows, tossed the family’s furniture into the street, and pulled sinks from the walls. Fighting spread through the streets. The governor of Illinois declared martial law, but it took the National Guard three days to bring the violence under control.

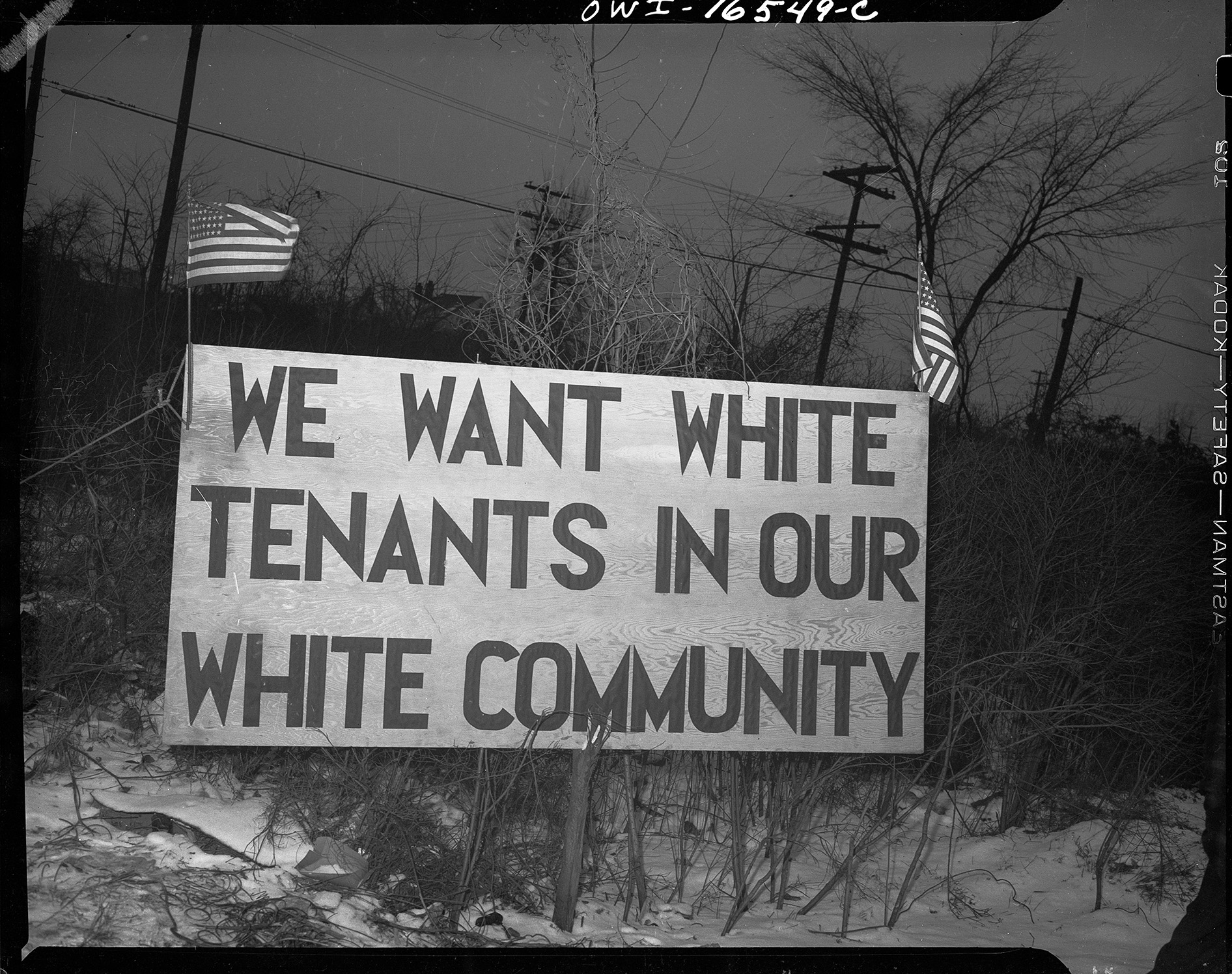

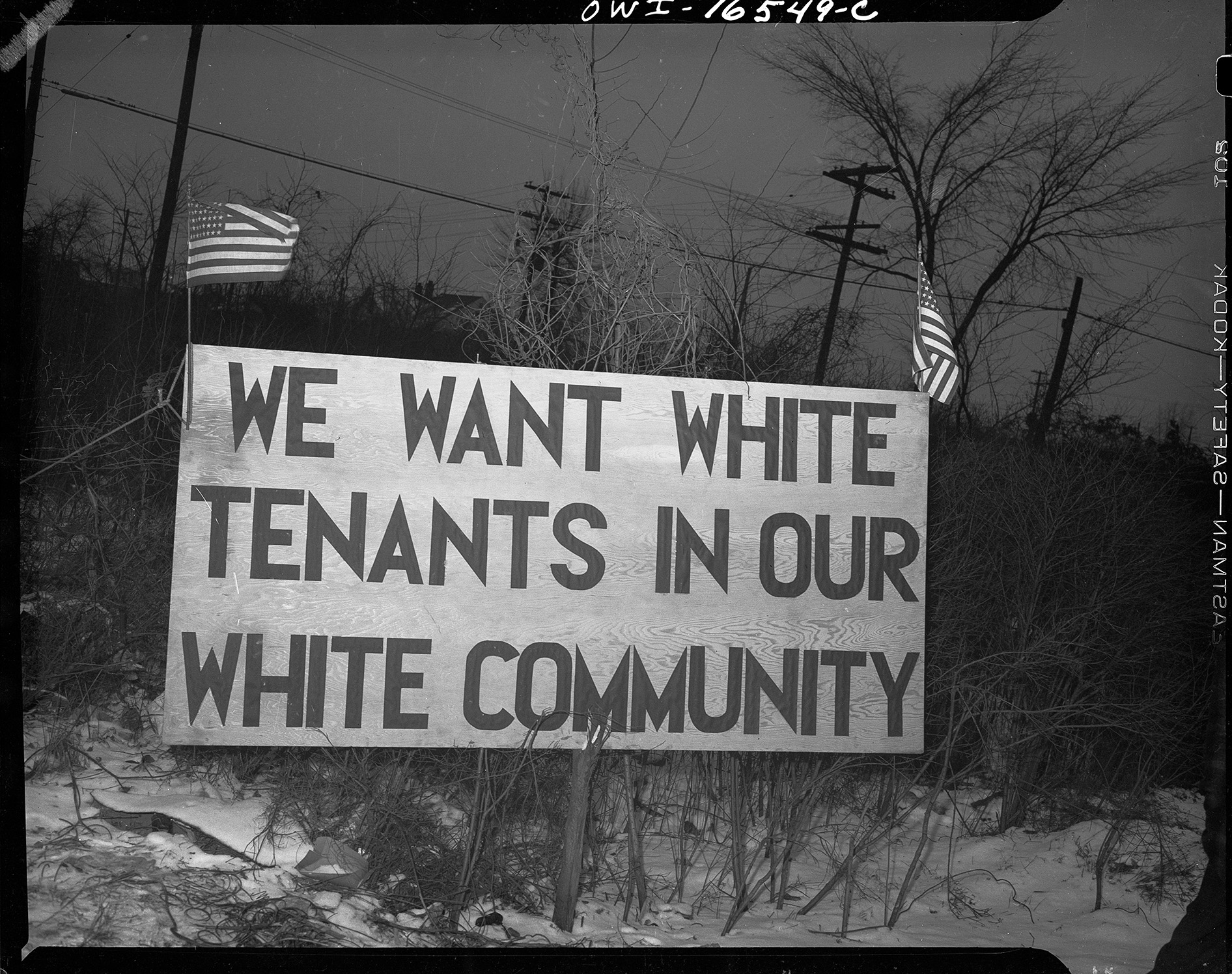

White residents living near the proposed site for Detroit Housing Authority's Sojourner Truth Homes protested and rioted to prevent Black defense workers from moving into the new units. They placed this sign directly across from the Sojourner Truth Homes.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Black Americans organized defenses of their own homes, often in the face of intense backlash. In 1925, a White mob surrounded the Detroit home of Dr. Ossian and Gladys Sweet. Along with nine other friends and family members, they remained there for two nights as the mob threw rocks into the home. Shots were fired from the second story by an unidentified person, killing one attacker and injuring another. All 11 people in the home were charged with murder. When the case went to trial, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) hired famous lawyer Clarence Darrow to defend Dr. Sweet—and won. This rare verdict affirmed that Black people, too, had the right to defend their lives and their property. But the victory did not stop the violence. Between 1945 and 1965 alone, White mobs protested and vandalized the homes of more than 200 Black families who had moved into the Sweet’s neighborhood.

Resource

A short documentary produced by Michigan Humanities about Detroit and the Sweet trials.

Mob action was often part of community efforts to maintain segregation. A crowd gathered to protest William Myers, a Black man, moving his family into Levittown, New York in 1957.

Courtesy of the Temple University Archives

The threat of violence was ever-present. Even when it did not flare up into attacks, it had a chilling effect on behavior that prevented people from testing the boundaries of segregation.Segregation: The act of separating people based on race, class, or ethnicity enforced through legal means or customary practice.

The church was everything. It was the park district that Black people could go to. It was the voting organization. It was the place where you can get soul food. It was the place where kids played and met each other. It was the place where you went for entertainment.

Attorney and Wealth Manager

ViewHide Transcript

It really and this is what's so hard now that you see all the political movements around churches and what should churches do and everything, but it's so easy to understand. For Black folks the church was everything. It was the park district that Black people could go to. It was the voting organization. It was the place where you can get soul food. It was the place where kids played and met each other. It was the place where you went for entertainment. And that's the big thing. A lot of people say. So what? Yeah. My dad and mom were used to the fact that church was entertainment too. So they went to church. Yeah, they were there. They loved Jesus. But they were there because that's what you do. And so it was even before this was common. It was something that was open, you know, 24/7, people would always be doing things there.

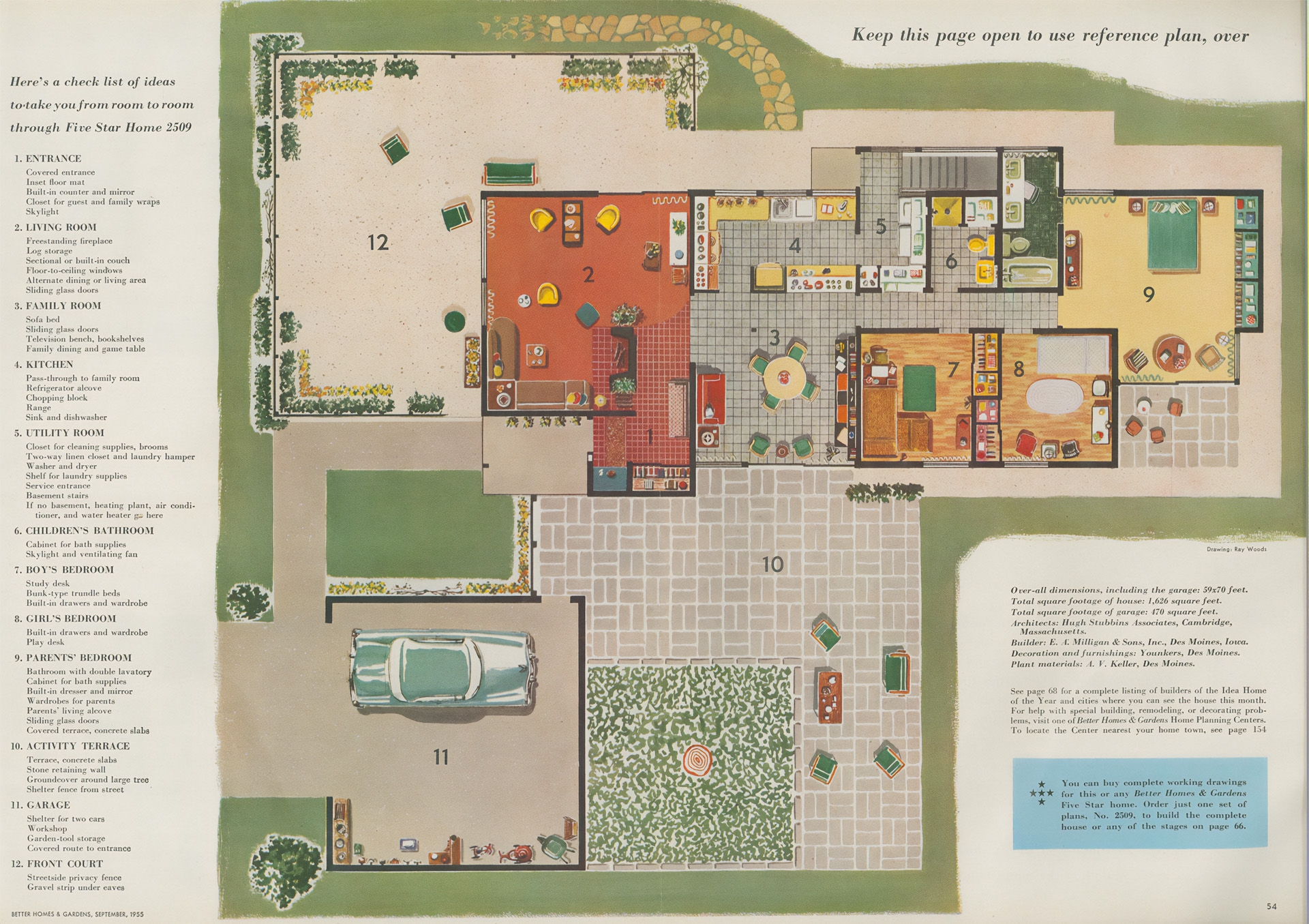

But violence was not the only tactic used to control where people lived. Laws and policies could do the same job with less bloodshed. Increasingly, White communities used legal strategies and discriminatory practices to achieve the same goals. These legal tactics were often more effective at maintaining segregation than the threat of violence.

Additional Resources

A short documentary produced by Michigan Humanities about Detroit and the Sweet trials.